🚗 Two roads to longevity →

February 16, 2026 • #

The latest issue of Res Extensa draws parallels between the story of Ford and Rolls-Royce and Stewart Brand’s framework of Low Road and High Road design, from How Buildings Learn.

We have polar opposite philosophies of design and construction that each is capable of producing things that well outlast their owners, and this applies to buildings, vehicles, and anything else we bring into our lives.

The Rolls endured through reliability. The Model T endured through repairability.

One inspired the devotion of its owner. The other devoted itself to its owner.

Initiation Well

The Initiation Well at the Quinta da Regaleira estate in Portugal.

🏢 Isometric NYC →

January 26, 2026 • #Using a combination of Claude, Opus, Nano Banana, and lots of satellite imagery, Andy Coenen built this incredible pixel art map of New York City. It’s like flying over a realistic version of SimCity 2000.

In this post he details his process for building it.

See the full resolution, zoomable map here.

Mysticism keeps men sane. As long as you have mystery you have health; when you destroy mystery you create morbidity. The ordinary man has always been sane because the ordinary man has always been a mystic. He has permitted the twilight. He has always had one foot in earth and the other in fairyland. He has always left himself free to doubt his gods; but (unlike the agnostic of today) free also to believe in them. He has always cared more for truth than for consistency. If he saw two truths that seemed to contradict each other, he would take the two truths and contradiction along with them. His spiritual sight is stereoscopic, like his physical sight: he sees two different pictures at once and yet sees all the better for that. Thus, he has always believed that there was such a thing as fate, but such a thing as free will also.

— G.K. Chesterton , Orthodoxy →

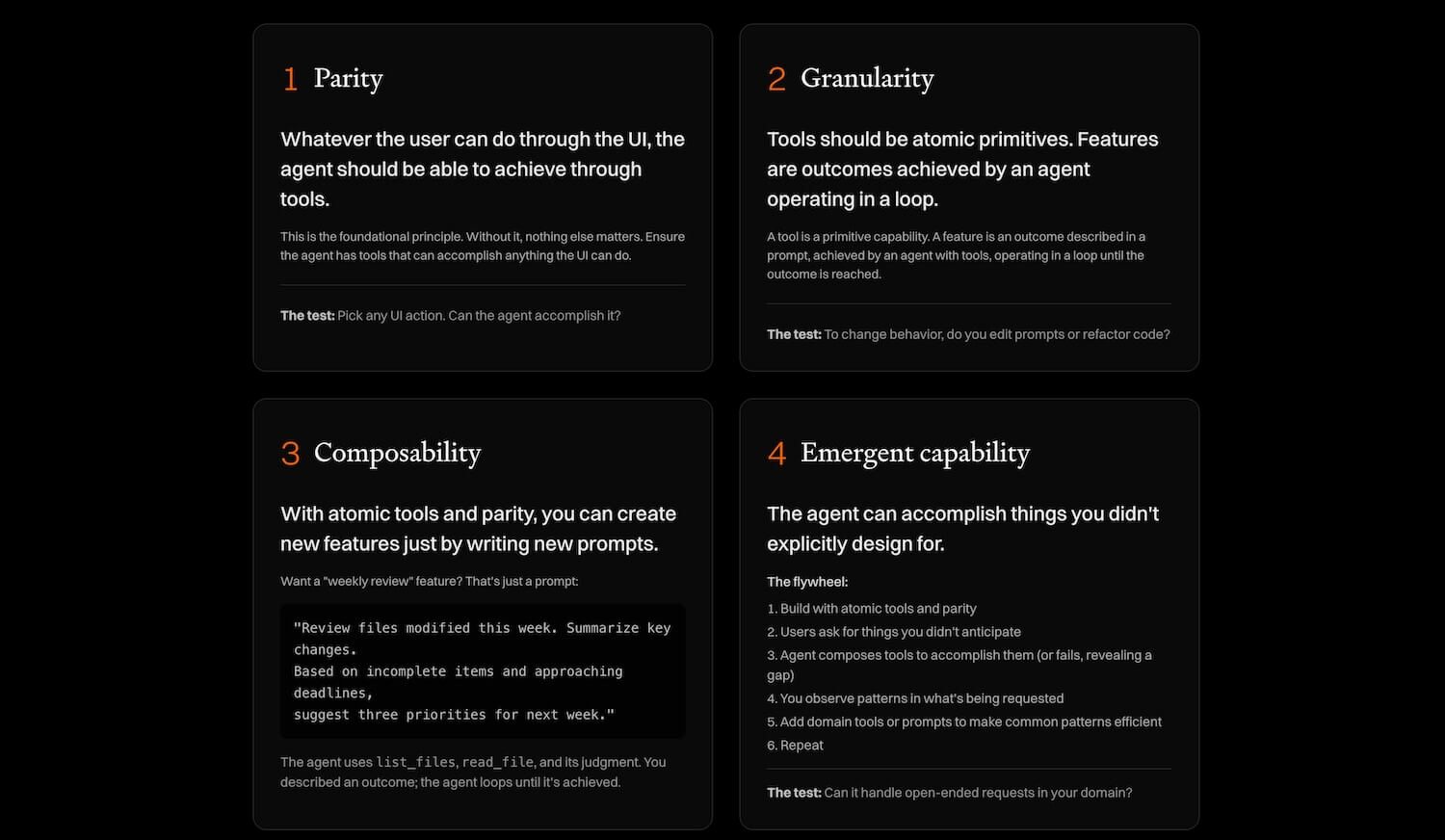

🤖 Agent-native architecture →

January 22, 2026 • #The folks over at Every published this excellent guide to a new paradigm for software, using what they call “agent-native architecture.”

In short the idea is that your mental model for thinking about what you’re building shouldn’t be focused only on user interaction, but anything you build should be usable by an agent, too.

So software should now be built around concepts like composability, reusable, callable primitives, and emergence. Sometimes an AI can find uses and things your product can do (and that users want to do) that you didn’t plan for. Thinking agent-native will have you building and prioritizing things with a different architecture in mind.

When we can design software around users setting goals and having agents pursue them, we end up with something much different than thinking only in database schemas and CRUD.

🚦 Resistance is signal →

January 22, 2026 • #Luca Dellanna on Resistance:

The point is that going to the gym is an activity, like many others, where you can technically produce its inputs in a negative mental state, but they won’t be good enough to bring satisfying results unless done with confidence. Therefore, chronic resistance is not something to dismiss or power through, but something to acknowledge, dissect, and address until resolved.

“Just powering through” resistance makes it more difficult to resolve its causes. In my view, the persistence and grit you develop getting used to powering through is a skill in itself, but Luca’s point is that resistance is telling you something about its causes. If you think deeply enough about the chain of causes, you can diagnose and treat at least certain aspects of the resistance to lessen its effect over time.

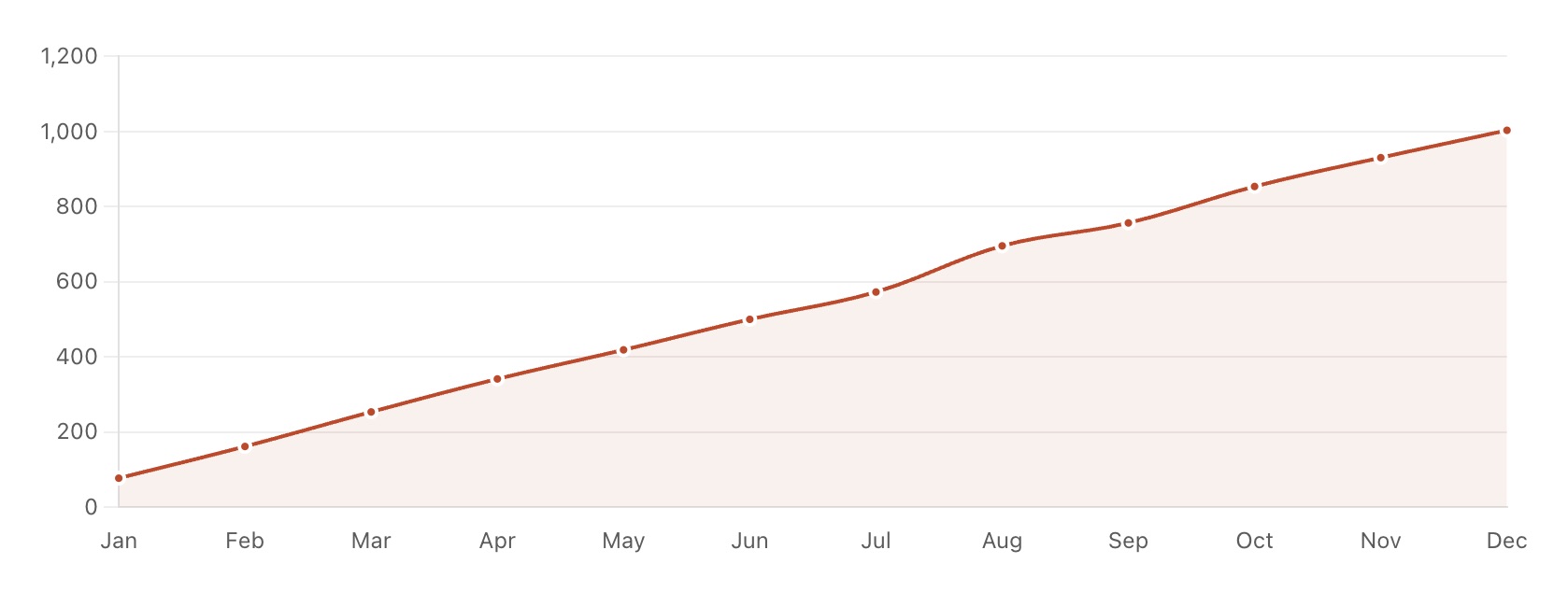

Running in 2025

January 21, 2026 • #I started out the year with the goal to run 1,000 miles. No other rules or restrictions, just get the miles in.

That meant keeping a steady pace throughout the whole year. It worked out to 2.74 miles/day, the hardest annual goal I’ve ever set by almost double. I did 650 a few years back.

I didn’t want to push the mileage too hard for fear of getting injured, but also didn’t want to lag more than a few miles off the pace in case I ended up sick or otherwise indisposed.

Here are some of the notable stats on the year.

Totals

| Stat | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Runs | 174 |

| Total Miles | 1,003.26 mi |

| Total Time | 167 hours (7 full days) |

| Total Calories | 119,362 |

| Total Elevation Gain | 32,180 ft |

Averages

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Miles per activity | 5.77 mi |

| Running time | 57:37 |

| Average pace | 9:59/mi |

| Average heart rate | 151 bpm |

| Temperature | 79°F |

Extremes

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Longest run | 40.03 miles (Pinellas Trail Challenge) |

| Max heart rate | 178 bpm |

| Hottest run | 93°F |

| Coldest run | 44°F |

What the American Constitution established was not simply a particular system but a process for changing systems, practices, and leaders, together with a method of constraining whoever or whatever was ascendant at any given time.

— Thomas Sowell , The Quest for Cosmic Justice →

The Turkish gulet

In today’s accidental internet discovery, I ran across the “gulet”, a two-masted style of sailboat from Turkey.

But the strongest prop of American order, Tocqueville found, was their body of moral habits. “I here mean the term ‘mores’ (moeurs) to have its original Latin meaning; I mean it to apply not only to “moeurs” in the strict sense, which might be called the habits of the heart, but also to the different notions possessed by men, the various opinions current among them, and the sum of ideas that shape mental habits.” Their religious beliefs in particular, and also their general literacy and their education through practical experience, gave to the Americans a set of moral convictions—one almost might say moral prejudices, as Edmund Burke would have put it—that compensated for the lack of imaginative leadership and institutional controls.

“It is their mores, then, that make the Americans of the United States, alone among Americans, capable of maintaining the rule of democracy; and it is mores again that make the various Anglo-American democracies more or less orderly and prosperous,” Tocqueville concluded.

“Europeans exaggerate the influence of geography on the lasting powers of democratic institutions. Too much importance is attached to laws and too little to mores. Unquestionably those are the three great influences which regulate and direct American democracy, but if they are to be classed in order, I should say that the contribution of physical causes is less than that of the laws, and that of laws less than mores… The importance of mores is a universal truth to which study and experience continually bring us back. I find it occupies the central position in my thoughts; all my ideas come back to it in the end.”

— Russell Kirk , The Roots of American Order →

For the rest, we should look for the improvement of society, as we seek our own individual improvement, in relatively minute particulars. We cannot say: ‘I shall make myself into a different person’; we can only say: ‘I will give up this bad habit, and endeavour to contract this good one.’

So of society we can only say: ‘We shall try to improve it in this respect or the other, where excess or defect is evident; we must try at the same time to embrace so much in our view, that we may avoid, in putting one thing right, putting something else wrong.’

— T.S. Eliot , Notes Towards the Definition of Culture →

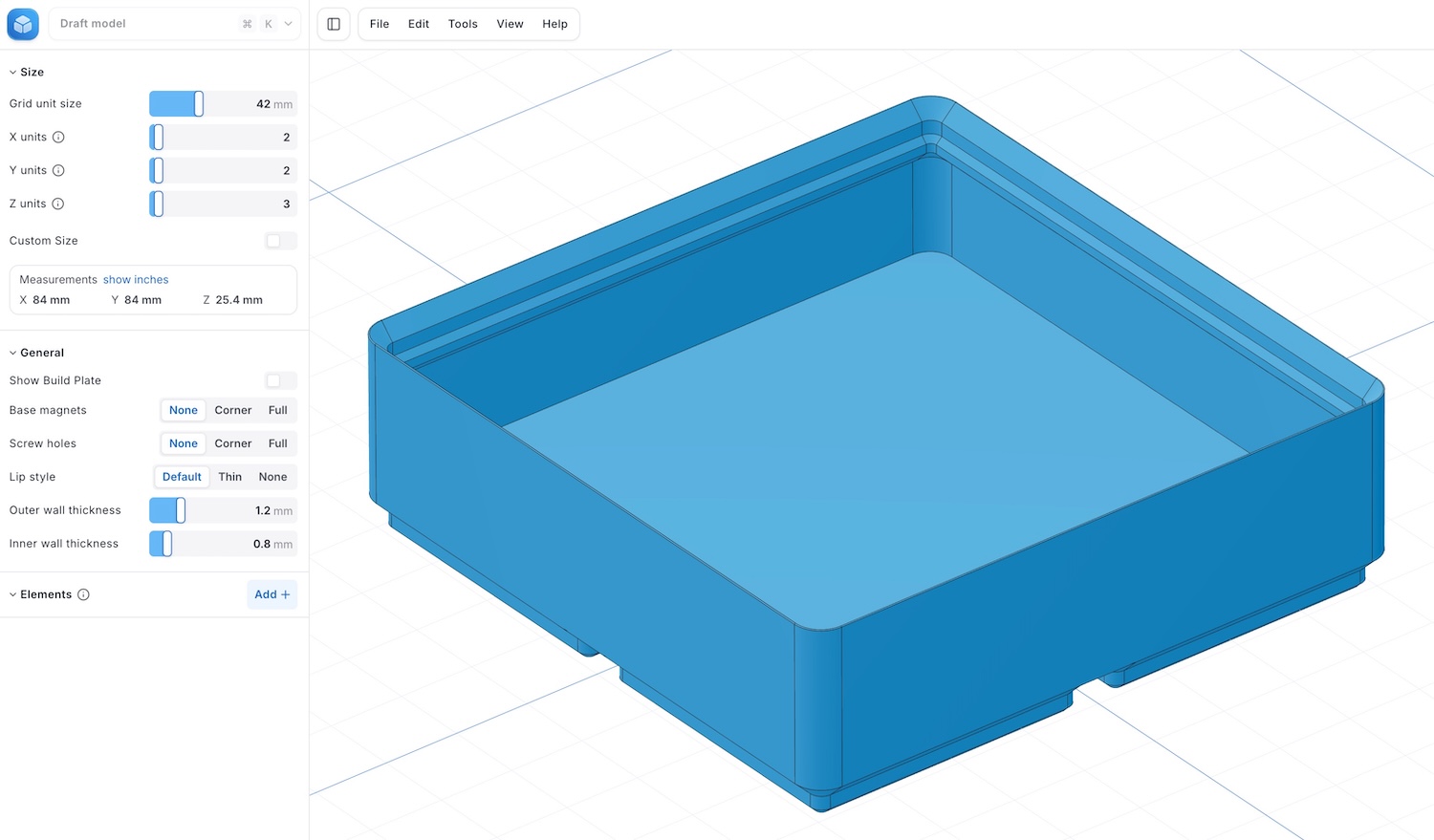

📦 Gridfinity Generator →

January 9, 2026 • #We’re deep into 3D printing over here after getting a Bambu Lab P2S for Christmas.

Mostly so far it’s been Everett and I finding models on the web and printing in different colors. Learning the basics of the slicer software and parameters, tweaking print settings. I’ve only just started dabbling back in CAD (and the skills are rusted all the way through). Fusion 360 is powerful, though. Planning to get Everett in there and learning some basics like I did when I was young — but back then it was like AutoCAD 5.0 or something.

One thing I wanted to do with this was create organization containers for drawers around the house. I discovered the Gridfinity system, which is an open source spec for printing modular trays and bins.

Then I found this Gridfinity Generator tool by Marcus Svensson. A slick web-based CAD for quickly creating custom grids and bins.

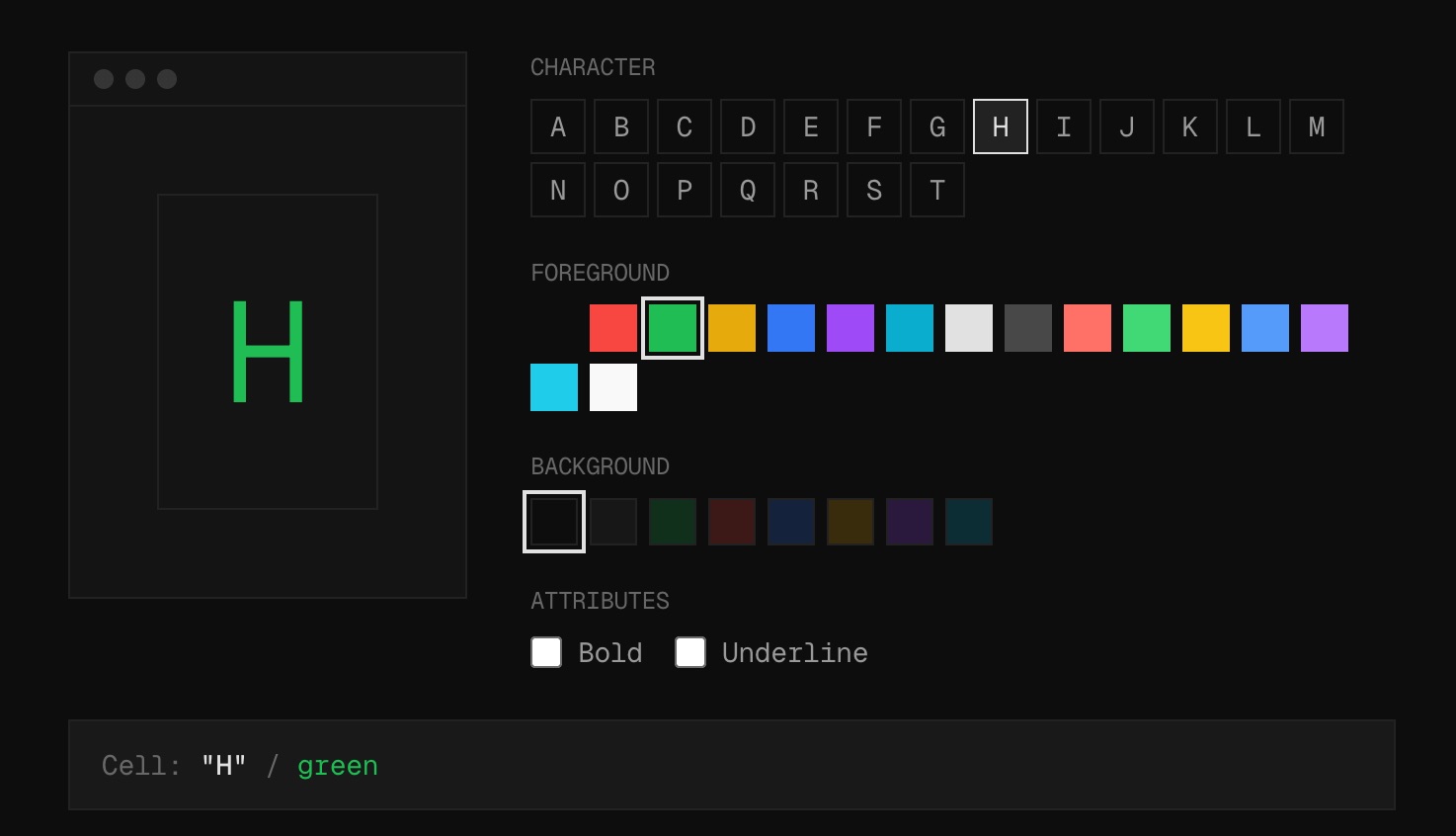

💻 How terminals work →

January 8, 2026 • #Software builders already spent quite a bit of time on the terminal. AI coding (especially Claude Code) has made the terminal not only an I/O mechanism for working with a system, but also an IDE and complete interface for building software.

Brian Lovin posted on X this site he built to explain the underlying tech of terminals.

We’re only seeing the very beginnings of the cool stuff that’s now possible — or rather worthwhile — to build when it only costs you a few prompts.

Herbie Hancock's start with Miles

Herbie Hancock on his introduction to Miles Davis.

Herbie got his start with Donald Byrd. And Byrd gave him the push to go seize the opportunity to join Miles’s second great quintet.

Jeff Huang writes about his 14 year old productivity system of simply using an ever-growing single text file to house everything.

To-dos, meeting notes, ideas. Everything.

Good reminder that you can have a high production function without 27 productivity tools.

In a wealth of information there is a poverty of attention.

— Herbert Simon

Making a Steinway piano

December 10, 2025 • #I ran across this documentary about the making of a Steinway grand piano.

The process of constructing one of these takes a year or more. It’s a great example of handmade craftsmanship in a world where we’ve mechanized every step, and oriented so much manufacturing to mass production. A Steinway is still made by a hundred masters, each honing a skillset for decades.

In a world where most everything is mass-produced, it’s no surprise that hand craftsmanship becomes a luxury good. As costs drop on manufactured versions, demand for the art form of hand tooling falls, skilled artisans begin to disappear.

I hope in more domains we’ll have a renaissance of handcrafted things. Not just on the demand side — with more people interested in buying them — but also in the supply: more kids interested in becoming furniture makers instead of financiers, artisans instead of attorneys.

One note I love on the Steinway process (and would be the same for many other crafts) is how many of its makers are working class locals, people with the nugget of a talent or a knack for craft that found a calling, showing up to the factory every day and filing that skill to a razor sharp point.

One day I’ll find a spare $100K for my own 9 foot ebony grand.

Science is organized knowledge. Wisdom is organized life.

— Immanuel Kant

Storehouses of history

December 7, 2025 • #As I was reading this article from Ted Gioia the other day, I noticed in this image he used a logo I recognized:

This is Hollywood Boulevard from the 1930s. Notice the Kress Building on the far side of the street.

It reminded me of our own Kress Building in downtown St. Petersburg, FL:

And the one in Tampa:

SH Kress & Co was a five-and-dime store chain that’s been defunct for over 20 years. Though you’d think there’s nothing noteworthy about a chain of the dollar stores of their day, they’ve left a legacy of interesting preservation-worthy architecture in cities across the United States.

Many of these still stand as beautiful specimens of historical architectural styles. The St. Pete one in Beaux-Arts style, Tampa in a Renaissance Revival. Or this gorgeous Art Deco example from Fort Worth, Texas:

In our modern culture of thrifty, modern, utilitarian design, there’s no way a corporation would invest in this kind of general public good.

In their day, these buildings functioned as stores: places to sell cheap things people needed. But they doubled as beautiful additions to the cityscape.

Are there any going concerns today about which we could say the same? What generic commercial building erected in the 2000s or beyond will be worthy of preservation and reuse in the 2100s?

⚖️ Return to smoke-filled rooms →

December 4, 2025 • #Jonah Goldberg with one of his classic broadsides against our broken primary system:

People hate on “smoke-filled rooms” because they think such venues give the rich and powerful undue influence over the nominating process. That is surely the case, though it did produce some pretty good presidents. It also produced some bad ones, though the blame for their failures can rarely be put at the feet of Fat Cats and Robber Barons. But the brief against smoke-filled rooms leaves out the fact that primaries are steamy garbage dumps for the same forces. The “money primary” and the “media primary” aren’t pristine processes either. Indeed, the primaries provide a form of “democracy washing” the influence of big money and rampant demagoguery—by the candidates and their donors and media boosters. What the primary system does is cut out the gatekeepers, the institutionalists, the small-r republican figures who care about the integrity of the party, the salience of various unsexy issues, and this thing called “governance.” When the party is in control, it still cares a lot about winning, but it also cares about the long-term viability of the party, its issues, and down-ballot candidates. Congressmen who want to get reelected might want a more boring presidential candidate that will put the party above his own ego and self-interest.

When some, like Jonah, want a return to smoke-filled rooms, the democracy-above-all crowd screams that with elites and gatekeepers between The People and their choices, it’s some kind of tyranny. What they fail to appreciate is how patently undemocratic the existing primary system is.

“Democracy washing” is such a great term to describe the current system. Pure, popular-democracy primaries give us a simulacrum of choice, without the underlying reality. If we don’t slog through the messy horse-trading and argumentation of the old 1880 style Jonah writes about during Garfield’s time, we trade better results for the ability to pretend The People are in the driver’s seat.

The patient slog through debate and argument is the process of better results simmering in the oven. Sure, we can bake the ribs in the toaster, but let me know how those turn out compared to giving them time to braise.

Like many things in our immature culture, we get so preoccupied with processes looking the way we want them to that we never do the mental trade-offs to determine if we’re getting better or worse results. Or if the thing we think is happening is even happening in the first place.

(The link to the article might be paywalled. But take that as tip to subscribe to The Dispatch.)

Return to Forever, Live from Jazzaldia

Return to Forever, Live from Jazzaldia San Sebastian, 2008.

A great live concert from a reunion of legends. Each of these guys was a noteworthy player in his own right. Return to Forever is one of the great jazz fusion projects. The whole discography is transformative.

I got to see Stanley Clarke live sometime around 2000. Incredible show and band.

The Abstraction of AI

October 1, 2025 • #OpenAI launched a major update to Sora yesterday.

There’s something about AI video that just doesn’t get me excited.

Sound on. pic.twitter.com/QHDxq6ubGt

— OpenAI (@OpenAI) September 30, 2025

Sure, it’s impressive: we’ve created black magic-levels of technology that can summon real-looking images from the ether. We can type a request and generate whatever movie we want.

But one of the things that makes film exciting is not only its quality or entertainment value, but the knowledge that a human produced it. There’s an aesthetic to the depth of human involvement in the process that Sora can’t substitute for. The more we close the uncanny valley visually, the more repulsed we are when we do find out it was “just AI.” We assumed human achievement, but we’ve been lied to.

I know, I know. We’ve had CGI in film for years. What’s the difference between Sora or Veo and the machine-assisted CGI from Transformers or something? This actually admits to the problem. People have disliked the overuse of CGI for years. The practical filmmaking of Christopher Nolan or George Miller or Ridley Scott stands out in a field full of CGI slop. CGI was once simply the seasoning on the meal, now it’s become the meal itself.

There Will Be Blood is impressive as a human feat of planning and executing on a vision, creating a collection of ideas and making them real – from script writing to performance to location selection to cinematography. The oil derrick explosion scene is impressive not just for what it is to look at, but because wow, humans made that happen.

Or think about music. Bach’s compositions aren’t merely impressive for their technical complexity or because they sound beautiful; what sits with you after hearing the Well-Tempered Clavier is that a human came up with that out of thin eighteenth-century air. The idea itself that a regular person could create something so original, textured, and interesting is an essential part if its value.

AI-generated media is stripped of this humanity. If we know a server farm generated those pixels or sound waves, we find ourselves disconnected from the impressiveness of human achievement. We have no way to relate to it. I know that playing a guitar is hard, but typing a prompt to get the computer to do it? I have no idea. Definitely sounds a lot less hard to me.

The AI bulls will claim the creativity is in the prompting, that talent will emerge able to steer these models toward genius originality. There’s something to this, for sure. All creators and craftsmen leverage the tools at their disposal. Modern woodworkers have power tools to assist in furniture making. Musicians have precision instruments and recording gear that allow them to realize a closer representation of their vision. Every advance inserts a new layer of abstraction between human imagination and a realized idea.

But as we move up the abstraction ladder of creativity, I’m less impressed by the human aspects of the achievement. Our hand is further removed from the output. Am I impressed by a song composition piped into a computer for a computer to play back? Sure, maybe. But I’m all the more impressed when the composer sits at the piano and plays it with their own hands.

I can simultaneously believe a CNC-sculpted statue is impressive to look at, while I consider the David to be both an impressive sight and impressive employment of human craftsmanship. Both require skills, but one requires more skills.

There will always be a market for authenticity. We have an appreciation for the humanity conveyed by a Van Gogh that simply isn’t there and can’t be there in a Midjourney image. No matter how fancy the prompt engineering.

🌐 Can you still be human? →

September 19, 2025 • #Iain McGilchrist:

Who does not now find themselves constantly busy? The young, the middle-aged and the old feel it alike. We are all time-poor; and time is not worth nothing. Time is life. Everything now is freighted with so much bureaucracy; and the bureaucracy is in an unholy alliance with AI. Together they massively, colossally, waste our time.

As he reminds us in this piece, we’ve got to stay vigilant here. Bureaucracy + AI is a dangerous combination for all our sanity (and likely worse).

We’ve already seen the enshittification of everything powered by financialization and dehumanization and “optimizations” for efficiencies, or for economies of scale. AI is superfuel for this nonsense.

I’m bullish on free markets and humans selecting against this world, as long as we have options. Let’s build and maintain those options.

Humongous Fungus

In LibertyRPF’s latest newsletter, he makes brief mention of the “Humongous fungus”, an Armillaria ostoyae fungus that covers roughly 2,385 acres of Oregon forest, and weighs an estimated 35,000 tons.

When you read enough about mycology, you find some science fiction-level stuff:

Most of this giant fungus is underground as a network of mycelium and rhizomorphs, black or dark brown structures that are kind of like roots or shoelaces.

The mushrooms you might see on a hike in the forest are just temporary fruiting bodies, like apples on a tree. The real organism is this vast, interconnected web beneath the forest floor that slowly spreads by feeding on tree roots.

Why are we looking for aliens in space? They’re already here on Earth.

📚 patternlanguage.cc →

September 2, 2025 • #I’ve been diving back into Alexander’s A Pattern Language the past few days.

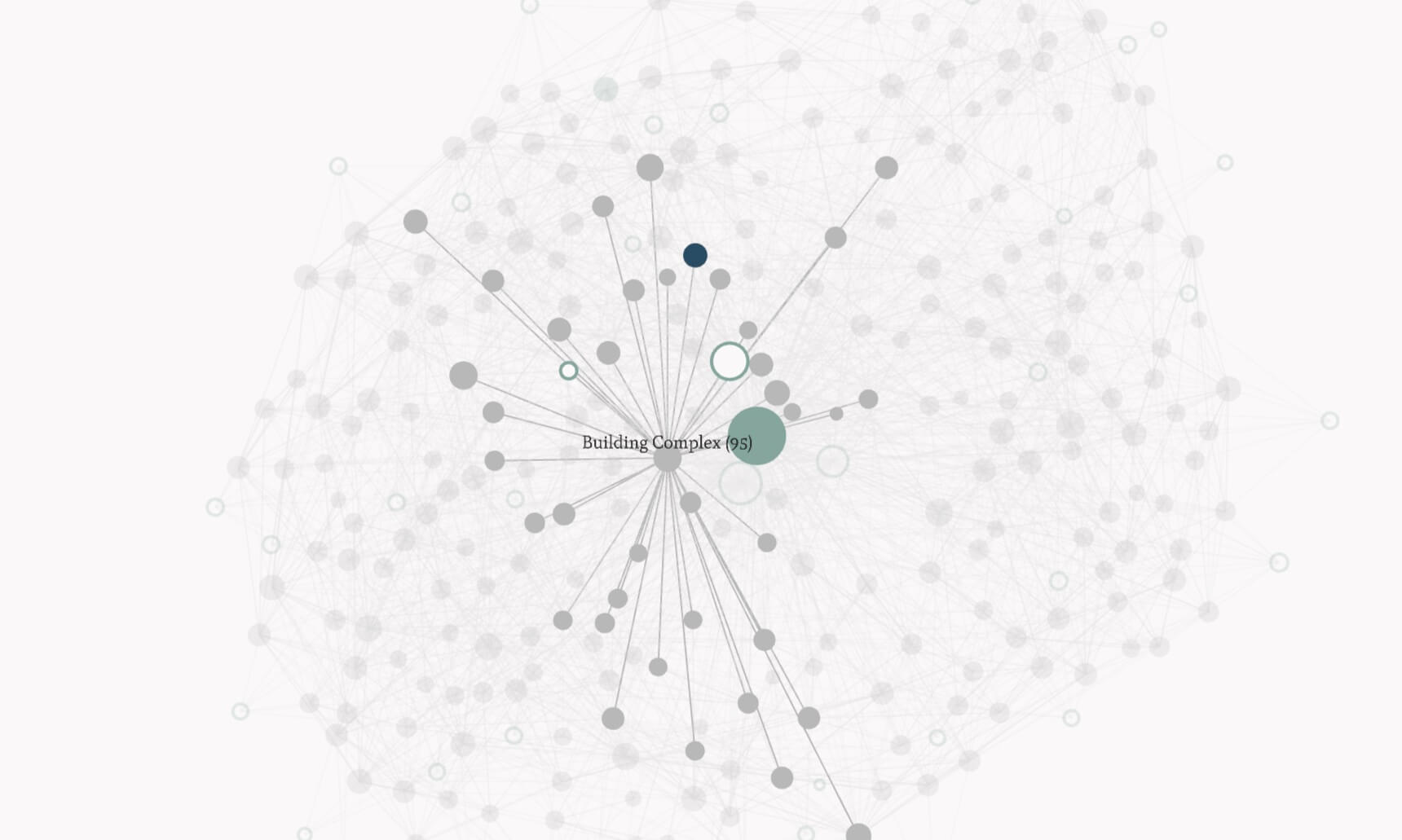

As I was making notes in Obsidian, it occurred to me that APL, with its interlinked system of patterns, could be an interesting medium for building a relationship graph around. Patterns connected to patterns.

Then looking around I ran across essentially this exact thing: a web-published version of an Obsidian graph of patterns.

Browsing to any pattern shows you the subgraph of adjacent patterns, with backlinks to each one. A neat way to traverse the relationships of Alexander’s system.

The circle of the English language has a well-defined centre, but no discernible circumference.

— Sir James Murray

We do not merely study the past: we inherit it, and inheritance brings with it not only the rights of ownership, but the duties of trusteeship. Things fought for & died for should not be idly squandered. For they are the property of others, who are not yet born.

— Roger Scruton , How to Be a Conservative

Also check out my newsletter, Res Extensa: