How to Listen to Jazz

by Ted Gioia

- Nonfiction

- Shelves: music, history, jazz

- 272 pages

- ISBN: 9780465060894 (Goodreads)

- Format: Kindle

- Buy on Amazon

How does one learn what defines a particular genre or style of music? A degree in music, studying music theory, or learning an instrument are all pathways to uncovering the structure of a tune. Years of careful study can certainly help if you want to be able to trace the connections of influence from one artist or composer to the next. But Ted Gioia makes the argument that listening is both the most accessible and best way to cultivate a richer understanding of music.

Sure, listening to music is mostly for enjoyment. But a careful, focused attention on the music itself uncovers patterns, structure, and similarities, without the need for a fine art degree in music theory. But, as with meditation or any other form of art appreciation, it takes practice to pay attention so closely.

Jazz music is complicated to deeply understand. Read up on the history and then take a quick listen to different styles: New Orleans hot jazz, bebop, fusion, free jazz, post-bop — listen to each one and you come away wondering how all of these fit in a single meta-category of jazz. What’s the defining attribute of the genre? And what are the specifics that separate one style from another?

One of the factors that makes jazz so confusing for so many people is its wildness, its diversity. Jazz has always been a melange of dozens of art forms, and has as its defining characteristic its ability to integrate other distinct styles — it’s like the English language in its openness to adopting words from outside. Just as English assimilates words from French directly into the dictionary, jazz music encounters the electrified instrument, and out comes fusion.

Jazz is uncurated, chaotic, open, free. Even the notion of an individual composition isn’t a requirement in jazz. A simple motif becomes the stage on which the individual players improvise. The entire genre is a platform for individual expression in the moment.

Above all, how do you penetrate the essence of a practice so imponderable that, when jazz icon Fats Waller was asked to define it, he allegedly warned, “If you have to ask, don’t mess with it.”

The chaotic openness of jazz make it difficult to pin down. But Gioia helps set some guideposts. His recommendations are not intended to be classroom rubric, but rather pointers for you to go listen and uncover the patterns.

The book begins with insights on the music’s foundational element: rhythm. All forms of jazz are built around the rhythmic cohesion of the group — what they call “swing”. With so much emphasis on extended improvisation, it’s important for the group to get locked in on one another. The famous groups like Miles Davis’s quintets or Basie’s band were exemplars of cooperative riffing, with the individuals going on extended solos while the rest of the band was along for the ride.

Here’s a final tip on how to tell if a band is in synch. When a group is working together effectively, the individual musicians don’t need to play so many notes. A soloist can toss off casual phrases, and each one seems to hit the mark. An accompanist can underplay, and the group still swings. On the other extreme—and I know this, once again, from painful personal experience—when the band’s rhythmic cohesion is floundering, each individual in the group is tempted to overplay.

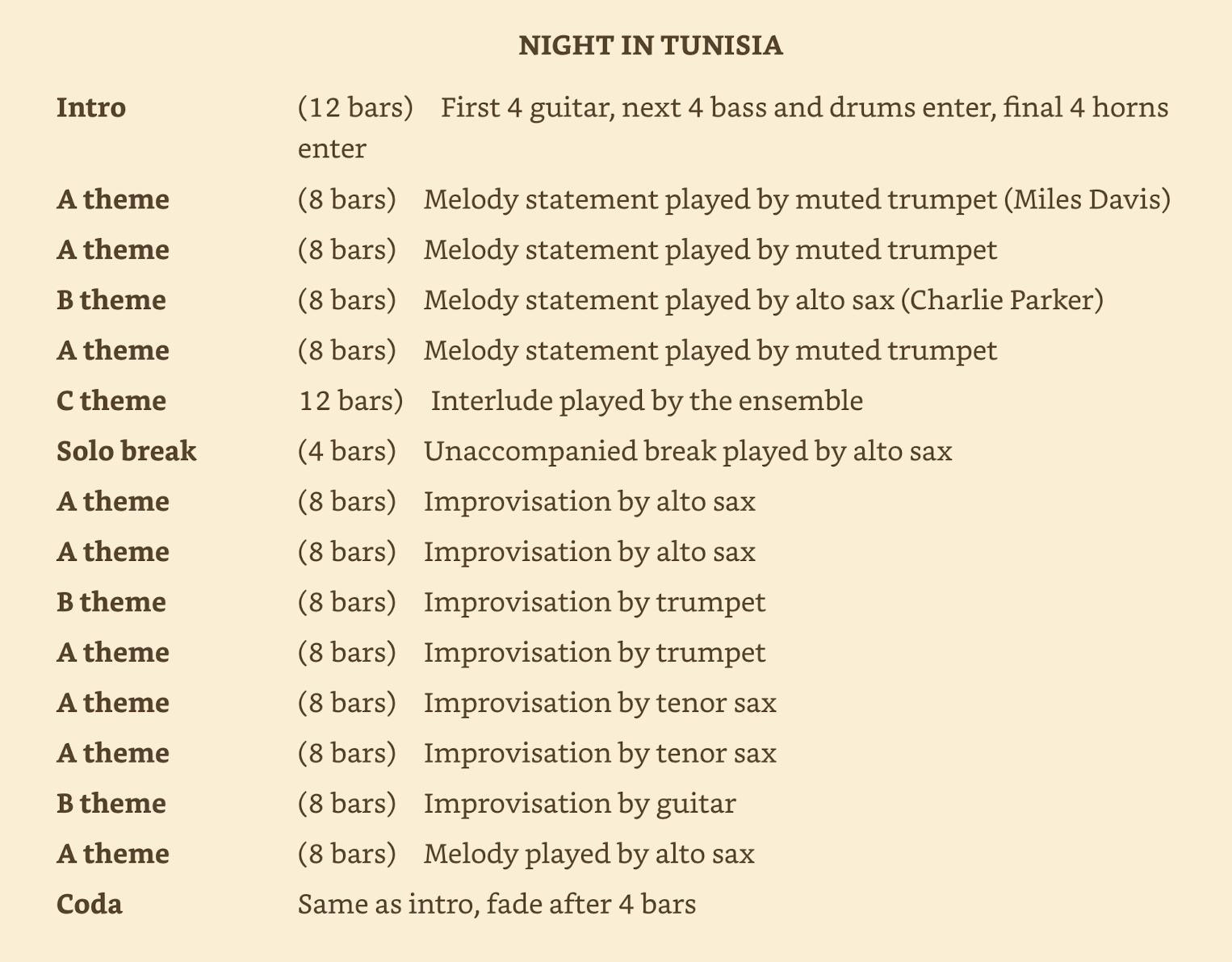

One of the most useful sections to me as a casual jazz aficionado was the chapter on the structure of jazz — the way tunes are composed of different themes, interludes, and solos. Here he walks through the structure of a number of different songs of different eras and styles. So you can put on Charlie Parker’s rendition of A Night in Tunisia and count along with the beat, listening for the different phases of the song’s structure:

When you listen to a song casually, especially as a non-musician and you’ve got the music on in the background, it’s hard to notice how a song is actually assembled. With some practice in active listening, you can map out tunes like this yourself.

By following music maps of this sort, newcomers to jazz begin to grasp that a style of music that initially sounds unconstrained and almost formless—the performers seemingly operating in the absence of rules, like gunslingers in a Wild West town without a sheriff—actually builds on a finely tuned balance between freedom and structure.

The meat of the book steps through styles of music over time. From its roots in New Orleans in the early 20th century, jazz made its way up the Mississippi to Chicago, then from their to centers of musical innovation like New York and Kansas City. With each section, Gioia recommends a selection of 8 to 10 tracks to explore as archetypes of each style. I found these lists helpful as he gives a diverse enough selection from different artists that you can listen to and compare to the styles that came before or after, listening carefully for the defining qualities of each.

As I was reading, I went through and made a playlist on YouTube of the recommended tracks in order. This made it easier to listen along with each chapter for the qualities of each genre as I was reading the descriptions.

The book wraps up with a section covering noteworthy artists from each era. The genre-definers like Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and others.

For an intermediate jazz listener like me, the book was a helpful guide to crystallize many of the key concepts and patterns that repeat throughout the jazz repertoire.

The goal in these pages is more one of connoisseurship and discernment. Think of it as akin to learning how to taste and savor wines, which may be assisted by some specialized knowledge, but can still be practiced by those lacking a degree in viticulture. Music is much the same. In hot music as in pinot noirs and cabernets, this cultivation of an informed taste is really the foundation for advancing more deeply into the subject.