A Globe of Connections

Connectography

Mapping the Global Network Revolution

by

Connectography

Mapping the Global Network Revolution

by

- Shelves: cities, urbanism, technology, geography, economics

- ISBN: 9780812988550 (Goodreads)

- Format: Kindle

- Buy on Amazon

Borders in today’s world are remarkably static, ever-present lines we all get used to separating territories as if there are hard barriers to interaction between the multicolored countries of your average political map of the world. Centuries of perpetual war, invasions, treaties, intermarrying monarchs, imperialism, and revolutions redrew the global map with regularity, but today we don’t see this level of volatility. When a new country is formed, a disputed territory shifts, or a country is renamed, it makes global headlines. It’s only every few years that you see territorial shifts.

This level of stability can be attributed to the interconnectedness of modern global society. In Connectography, Parag Khanna makes a compelling case for the dissolving relevance of international borders. His thesis is that cities are now the dominant focal point of human engagement and productivity rather than states, and that the grid of connection points between cities has largely superseded the importance of international borders: “a future shaped less by national borders than by global supply chains, a world in which the most connected powers—and people—will win.”

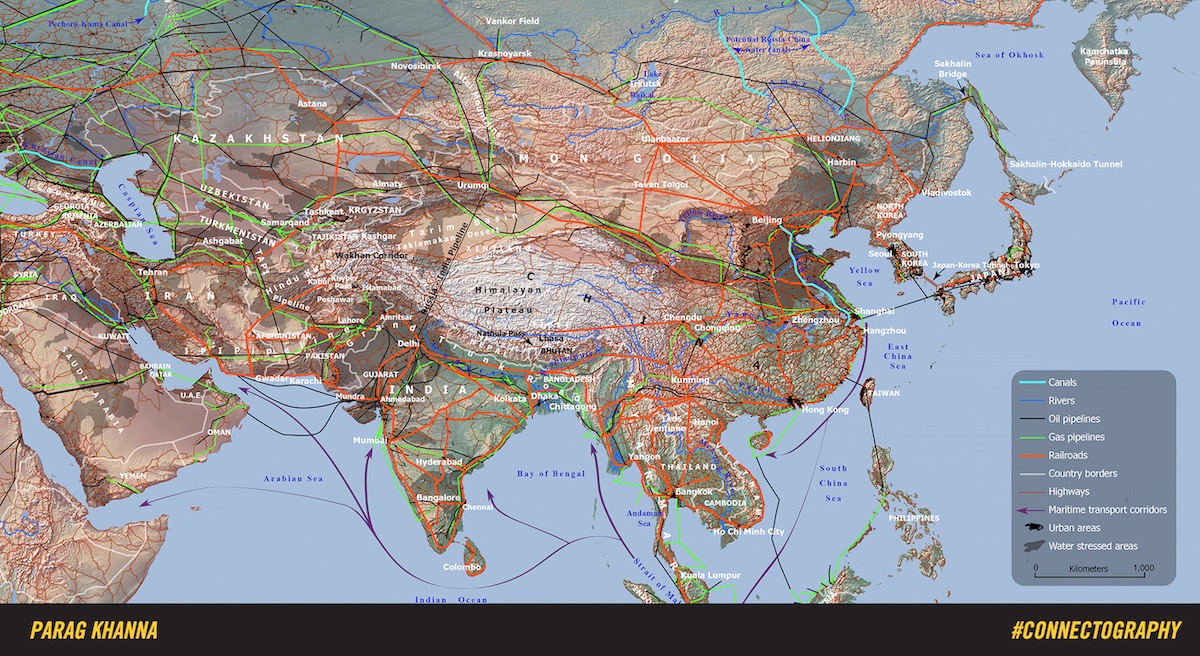

Asia’s web of connections

Asia’s web of connections

Worldwide economic growth has created a level of stability unprecedented in human history. In Thomas Friedman’s 1999 book The Lexus and the Olive Tree, he posits the “Golden Arches Theory” — that “no two countries that both had McDonald’s had fought a war against each other since each got its McDonald’s.” Meaning once economies are significantly integrated with one another, the cost of conflict increases, thereby deterring each side from sparring with one another. While this tongue-in-cheek theory offers an overly simplistic view of the world, the point still largely holds up today. Nations go to “economic war” more readily than armed conflict.

Expanding on Friedman’s theory from 20 years ago, Khanna clarifies that it isn’t specific enough to attribute stability to “globalization” in some broad sense. More concretely, it is interconnectedness that creates a shared sense of motivation, collaboration, and responsibility for progress. As he points out, some of the least connected places on earth are the ones with the least stability:

“Importantly, the geographies not knitting themselves together into collective functional zones—the Near East and Central Asia—are also generally where one finds the most failed states.”

The concept of “global cities” started to take hold in the nineties — cities that function as nodes on the global interconnected network thanks to the connective tissue of infrastructure: Shanghai, New York, London, Singapore, Hong Kong, and others. Modern telecommunications, energy distribution, and transportation networks wire people closely together while ignoring the man-made boundaries between nations, the social barriers of language and culture, and even the physical barriers in mountains and oceans. Khanna makes the case that we should redraw our maps to more vividly represent reality on the ground:

“The absence of the full panoply of man-made infrastructure on our maps gives the impression that borders trump other means of portraying human geography.”

With increasing human migration to to urban areas, the city is where human activity now takes place. Cities (especially global ones) are beginning to form economic and diplomatic bonds with one another, regardless of the proximity or cultural similarity of their respective states. Central to Khanna’s point is that this economic and technological expansion has enabled supply chains to drive the social order:

“Supply chains are self-assembling and organically connecting. They expand, contract, shift, multiply, and diversify as a result of our collective human activity. You can disrupt supply chains, but they will quickly find alternative pathways to fulfill their missions.”

Globalization and the ever-multiplying division of labor allows for even historically landlocked places excluded from the global economy to specialize and “plug into” the network, taking their place in the flexible supply chain. The competition to become a new link in the supply chain creates positive forces that motivate people to create value for others up the chain. What used to be a hierarchical order between large states has dissolved into hundreds or thousands of largely-independent nodes that invest in their own specialties, a decentralization that reworks the old world order:

“The interstate puzzle thus gives way to a lattice of infrastructure circuitry. The world is starting to look a lot like the Internet.”

One focal point of the book is on the policy tactics cities are using to embrace connection and openness within their current constraints of monarchy or centralized control. The “Special Economic Zone” (SEZ) is a tool in the arsenal gaining acceptance around the world to invite foreign investment in the form of corporate presence inside of a nation’s borders. As Khanna points out, they’re gaining in popularity with “more than four thousand SEZs around the world, the pop-up cities of a functional supply chain world.” Acting as if there’s little to no barrier to collaborative development, a US-based company can establish a presence in Shenzhen, Dubai, or Batam that was impossible 20 or 30 years ago. Powered by the infrastructural connections brought about by the internet, containerized shipping, and international financial investments, these SEZs provide havens for countries to ignore one another’s political boundaries. In places like China’s Pearl River Delta, this interconnectedness with other global cities has enabled unprecedented growth — now with nearly 60 million people plugged into an economy by leveraging its network proximity to the other centers of gravity, like a critical router in a network topology diagram. The savvy of the local government in attracting multinational corporate investment (even though counter to much of the party dogma) can be credited with an enormous jump in quality of life for millions of former rural Chinese that have since migrated to the region.

A lively, connected Arctic

A lively, connected Arctic

The book is full of rich examples of locales as diverse as colonial Southeast Asia, the Caucasus, the Near East, and East Africa. A theory this compelling on modern economic freedom and progress requires connecting the dots of history to understand how we arrived here. Throughout the book there are maps peppered in to visualize the pervasiveness of infrastructural connection. There’s even a website devoted to making the maps interactive, so you can see for yourself how interconnected the world already is, regardless of political rhetoric of the day.

Connectography is an engaging read for anyone interested in geopolitics, international relations, and geography. Khanna has developed a thought-provoking theory of economic development for the modern era.

Some fun facts from the book:

- 🏙 In 1950, the world had only two megacities of populations larger than 10 million: Tokyo and New York City. By 2025, there will be at least forty such megacities.

- 🇲🇽 The population of the greater Mexico City region is larger than that of Australia, as is that of Chongqing, a collection of connected urban enclaves spanning an area the size of Austria.

- 🏗 China consumed more cement between 2010 and 2013 than America did in the entire twentieth century.

For more on Khanna’s work on Connectography, check these out:

- How megacities are changing the map of the world — Khanna’s TED Talk on Connectography

- A New Map for America — redefining the US map based on economic “mega-regions”

- How Hyperconnected Cities are Taking Over the World