This is the first book review post since I put up my [library section]({{ site.url }}/post/the-library/). I hope to do more of this in the future with each new book I add to the collection. Enjoy.

The Story of Maps took me a while to get through, but it’s the most comprehensive history I’ve seen on the history of geography and cartography.

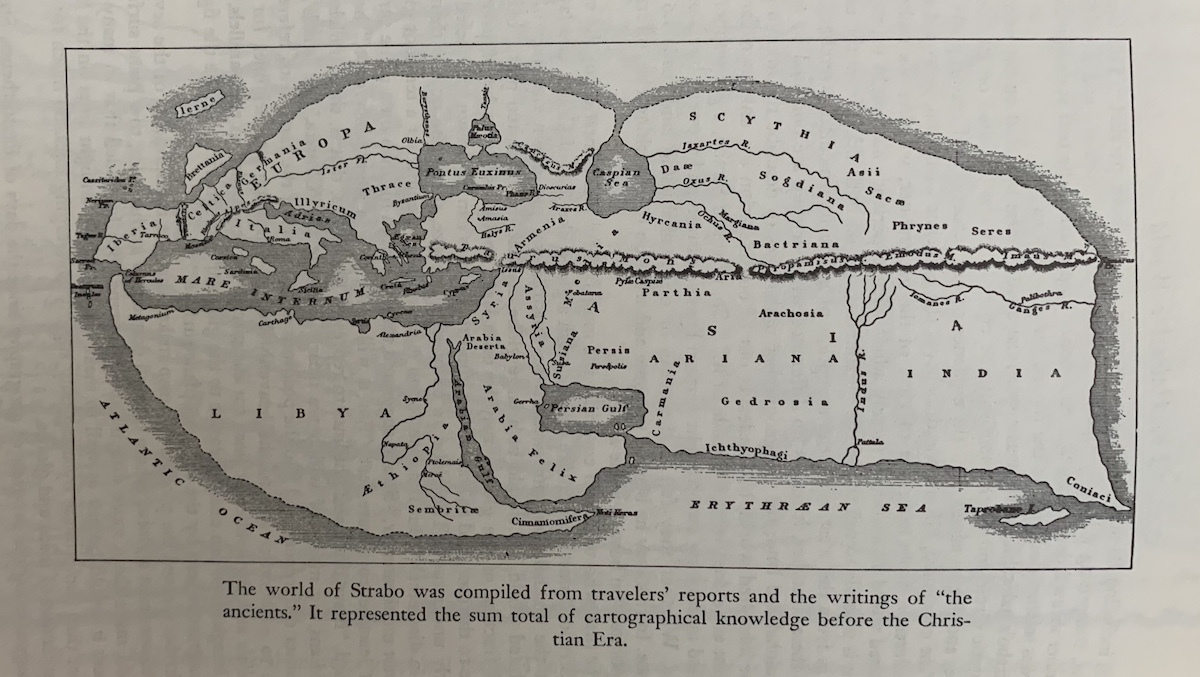

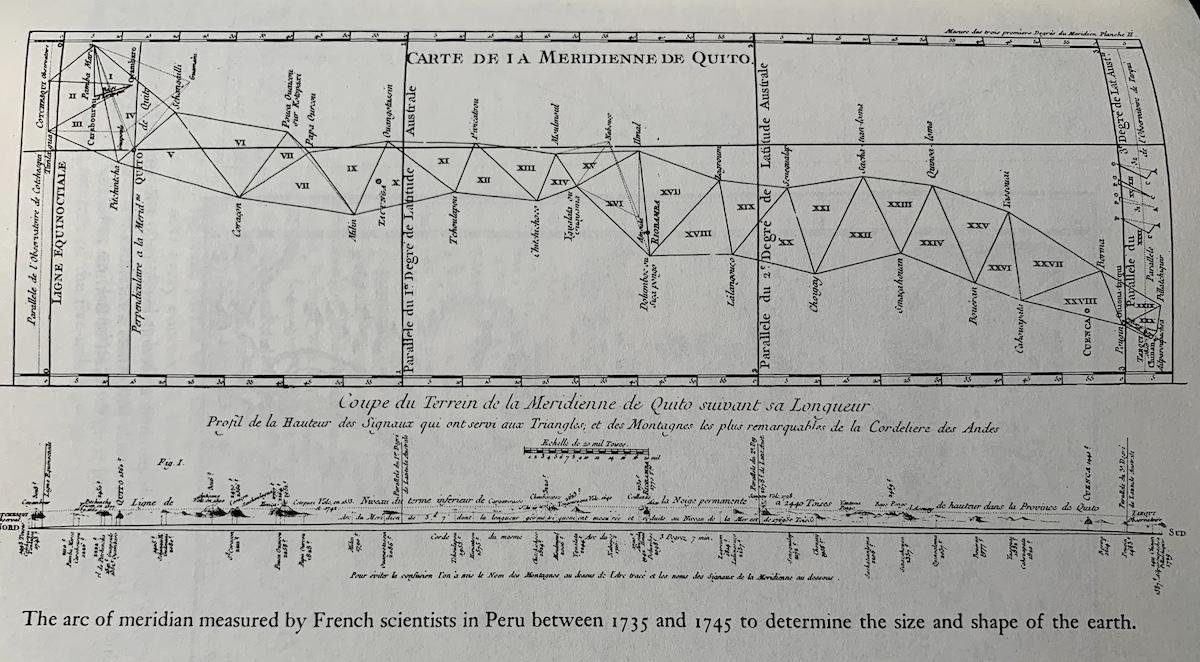

Of particular note was the history of the figures in antiquity, their discoveries, and the techniques they used to advance the science of mapmaking. From Strabo, Eratosthenes, and Ptolemy to Ortelius, Mercator, and Huygens, Brown is extremely thorough in giving each of the critical figures their space on the page. The book is peppered with illustrations that give visual context to many of the maps and equipment devised by the cartographers, scientists, and inventors. I found myself down numerous Wikipedia rabbit holes whenever I’d see arcane place names in the periphery of the worlds known to the Greeks, Romans, or Carthaginians.

Naturally I had a good understanding of how most geographical systems and tools work — longitude and latitude, equinoxes, the tropics, time zones. What was a delight to read was the historical context in which these things were discovered or developed by people with little to no access to anything we’d consider “technology.” For millennia, making maps meant getting on a ship, horse, camel, or your feet, writing down what you saw, observing celestial patterns in the sky (or Jupiter if you were really clever), and tediously aggregating enough detail to make a representative picture of the world. Today we laugh at the distorted, backward views that scientists like Strabo assembled as his “known world,” but given the available resources, it’s honestly stunning anyone could map anything beyond their own village.

Brown addresses this in the introduction, that the history of science is one of failure and persistence:

The history of science as a whole is the record of a select group of men and women who have dared to be wrong, and no group of scientists has been more severely criticized for its errors than cartographers, the men who have mapped the world. Hundreds of weighty tomes have been written to prove how very wrong were such men as Ptolemy, Delisle, and Mitchell. For every page of text, for every map and chart compiled by the pioneers of cartography, a thousand pages of adverse criticism have been written about them by men who were themselves incapable of being wrong because they would never think of exposing themselves to criticism, let alone failure.

As cartoonish and silly as most maps made prior to the Renaissance appear, the historical frame Brown assembles around these works gives a great appreciation to the struggles of the pre-modern cartographer’s reality.

Venturing Into the Unknown

For most of human history, the map of the world was really one of the Mediterranean Sea. We’ve all seen ancient maps with extreme distortion beginning only a few hundred miles from the Med coast. One of my favorite sections of the book is about the Phoenician pioneering of navigation and sea charts, one of the earliest forms of map that had practical use beyond the artistic. Rather than an academic approach to the development of charts, the Phoenician methodology was driven by necessity. As a trading civilization with origins in modern-day Lebanon, seafaring was essential to the growth of the empire, therefore the need for charts purely for livelihood was paramount. As far back as 1200 BC, Phoenician sailors were cruising throughout the Mediterranean and Adriatic, and are even thought to have circumnavigated Africa in 600 BC. The role their knowledge of geography played put them at the center of importance to dozens of neighboring civilizations, making them the first truly expansive “trading” nations:

They mastered many of the “secrets of the sea” and the more important secrets of the heavens, but just how much they knew about the sea and the universe as a whole, and how far they were able to develop the science of navigation, history does not say. Certainly the Phoenicians never said. Their skill and their willingness to sail where others dared not go gave them a peculiar power over more powerful nations bordering on the Mediterranean who depended on them to transport their merchandise and fight their naval engagements for them. They were indispensable to the great political powers. Sennacherib, Psammetichus, Necho, Xerxes, and Alexander all depended on them to maintain their supply lines and transport their legions.

But they left no written record of their knowledge. What we know about their contributions and extents of their exploits is through the marks they left on the places they visited. The lack of any left-behind documentation was likely intentional — they guarded intensely their knowledge of sea lore:

It was all the same to the Phoenicians. They knew what they had and guarded their secrets concerning trade routes and discoveries, their knowledge of winds and currents, with their lives. The influence of sea power began to manifest itself at an early date, and the Phoenicians were cordially detested in Greece if not elsewhere. They were also feared.

This brings to the forefront an interesting thread that runs throughout the story: the intimate connection between mapmaking, military intelligence, and corporate competitive secrecy.

War & Commerce Drive Discovery

A common theme with many advancements in science, not just geography and cartography, is the need for intelligence to defeat an adversary. War-making has a longstanding relationship with geography since the time of the Babylonians and Greeks, and still does today. Throughout the Age of Discovery, many of the modern inventions we still use todayfor surveying, navigation, and cartography — coordinate systems, projections, and more — were endeavors financed by kings and tyrants in service of conquest. Until most of the seas were explored and documented by the 19th century, the domain of cartography was divided between three main groups: private enterprise, government sponsorship, and commercial atlas publishers (who were only left with the scraps the other two didn’t care about, which wasn’t much). In the first two concerns, secrecy was a default — a necessary element to maintaining an edge over the market or the enemy. In the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company developed a “Secret Atlas” for the exclusive use of the Company. Like a Google or Apple of 400 years ago, they invested heavily in developing maps to leverage for commercial gain, employing their own cartographers to develop highly protected data. Though unlike today’s private enterprise, they saw no advantage from exposing any of their work to the public:

This remarkable lot of 180 maps, charts, and views was made for the exclusive use of the Company by the best cartographers in Holland. Included in the collection, and of the utmost importance, was a series of consecutive survey charts, which, when pieced together, show the fairway through the Indian Archipelago, the route to India along the coast of Africa and through the Indian Ocean, and the best course to China and Japan. In addition there were many single charts on a larger scale which showed in detail the small islands and atolls that played an important part in the hit-and-run battles on the high seas. There are Colombo on Ceylon, Bantam, Makassar, Atjeh, and the Portuguese stronghold of Goa; Ternate and Makian and the strategic outpost of Mauritius.

The ties were close between the East India Companies and their patrons in their respective governments. The explorers of the age were all funded by monarchs in search of claim-staking, empire-building, trade, and colonization. Navigators saw themselves as the “keepers of secret knowledge” when it came to fundamentals we consider givens today (even obsolete) — like the development of the astrolabe, the quadrant, celestial charts, and accurate marine chronometers for measuring longitude1.

The “Modern” World of Geography

Even in the modern era, for many decades governments were the only entities capable of bringing to bear the resources to map countries or continents. Today it’s easy to discount the monumental effort required to create a map of an entire country, since we have hyper-large-scale data accessible on our phones and watches. But for most of human history, knowing a place meant putting feet on the ground there. As late as the Second World War this was how mapping was done. Here’s Brown on the Allied strategy for gaining an edge on the Axis:

The fundamental data in many cases were not to be had by gift, theft, or purchase. A map is no better than the sources from which it is compiled, and too often the sources were not to be had, at least so far as the Allied nations were concerned. No amount of synthesis, scientific or artistic, no amount of high-speed printing on fine paper could remedy the fundamental lack, the basic objective of cartography — an accurate survey of the ground.

At the time of the book’s publishing (1949), the author couldn’t have imagined the world we live in now. Near the end, Brown sums up the current state of mapmaking as one driven by government bureaus and the post-war surge in the number of skilled surveyors, newly-minted after years of investment in the effort to supply mapping intelligence to warring nations around the world. Since the 1960s, the world of mapping has been propelled by the Space Age — from U-2 spy planes and Corona satellites during the Cold War to the Key Hole program that began for reconnaissance purposes and kickstarted the commercial satellite industry. While governments and militaries are still enormous contributors to Earth sciences and geography, private enterprise has taken the mantle of cutting-edge map data collection. All of us consume maps as a default behavior today, geotagging pictures, navigating with turn-by-turn directions, and searching for the next restaurant to visit happen as a matter of course. Machines are gathering data at a rate we aren’t even able to consume. For thousands of years, people were content if the could know only the physical space. Today physical geography is seen largely as a “solved” problem. We’re now able to map human movement patterns, financial transactions, weather, wildlife, events, and anything else that happens in space and time.

A Mine of Information

The bibliography is a treasure trove of further historical works. I still have to parse through it and flag other books that look interesting for further reading.

The one major critique I have of the book is its encyclopedic depth. If it were written today, much of the excruciating detail would be left on the cutting room floor, probably, but it’s bearable once your expectations are set. For certain elements of the history, I actually welcomed the level of detail. It prevented me from having to do further Googling to dig in on the parts I was more interested in. But quite a bit of it is unnecessary belabored.

I highly recommended The Story of Maps to the geographer with an interest in history. I haven’t found a better resource that starts at the true beginning. Most histories of science or cartography won’t go all the way to Anaximander and Strabo, but Brown showed no fear in devoting 100+ pages to the foundations of the science.