An Open Database of Addresses

One of the coolest open source / open data projects happening right now is OpenAddresses, a growing group effort assembling around the problem of geocoding, the process of turning human-friendly addresses into spatial coordinates (and its reverse). I’ve been following the project for close to a year now, but it seems to have really gained momentum in the last 6 months.

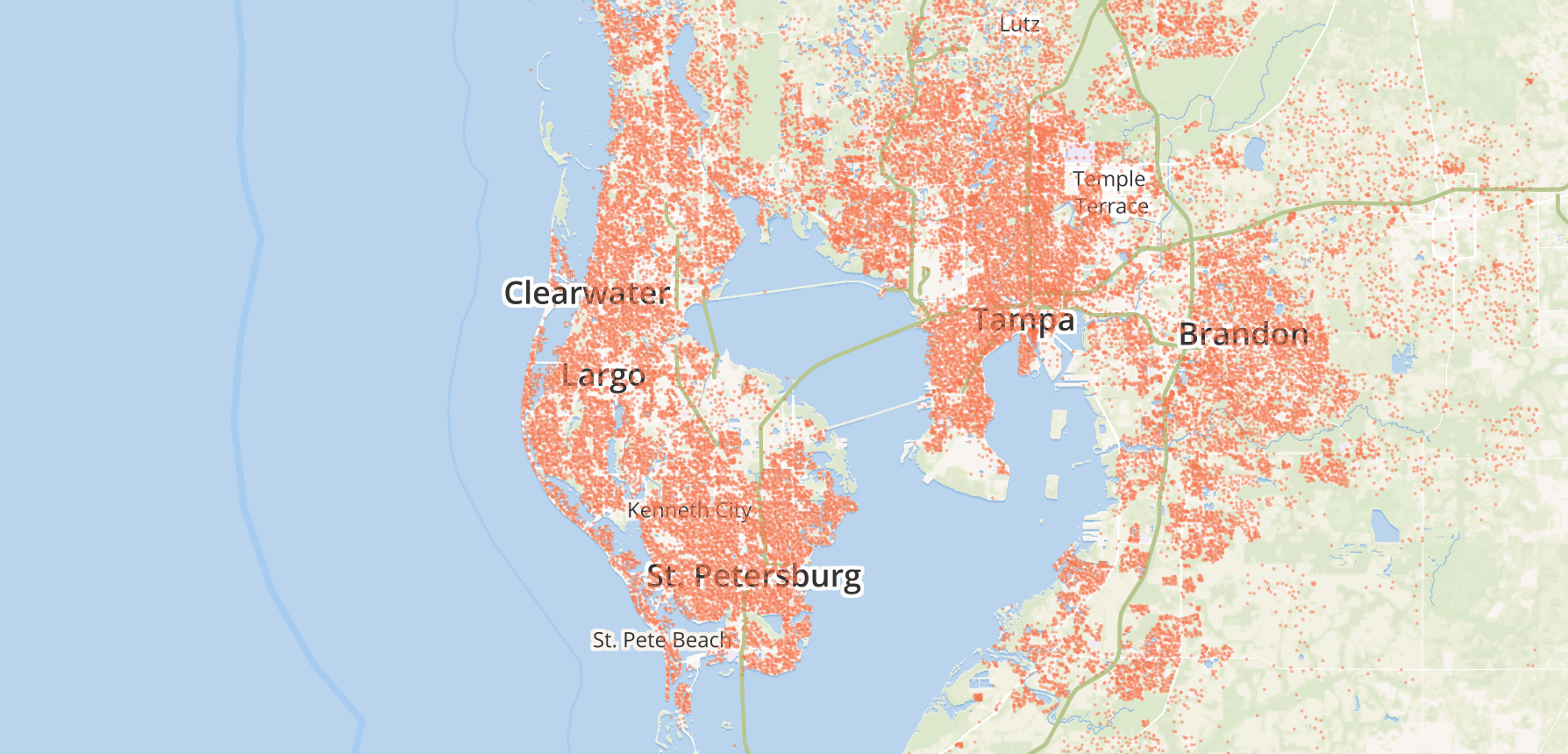

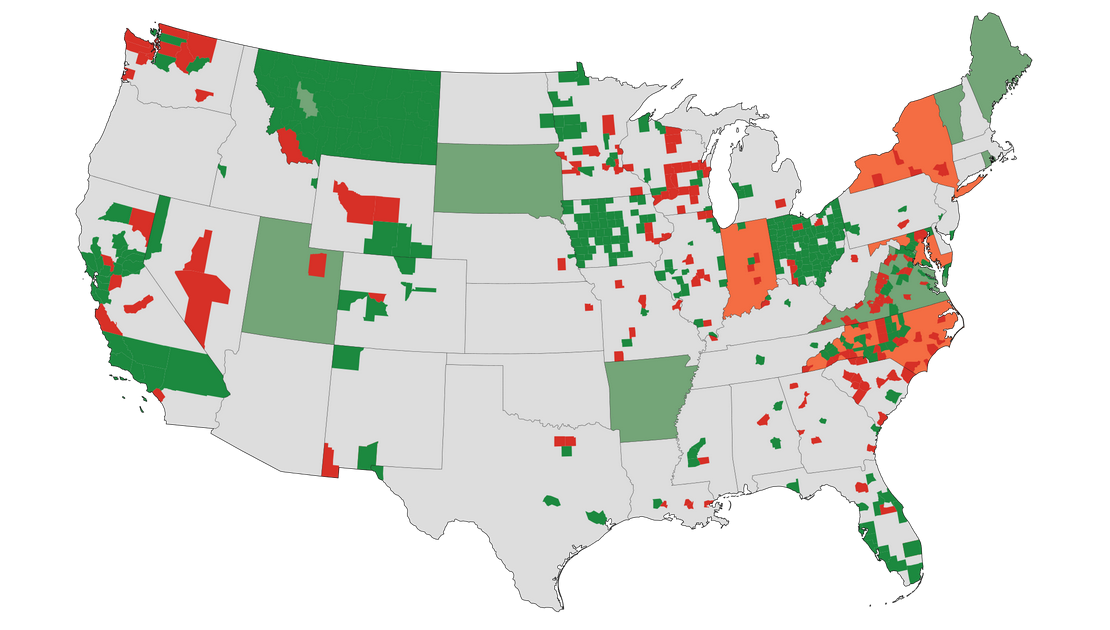

The project was started last year and is happening over on GitHub. It now has over 60 contributors, with over 100 million aggregated address points from 20 countries, and growing by the day. There’s also a live-updating data repository where you can download the entire OpenAddresses dataset online—it’s currently at about 1.1 gigabytes of address points.

Here’s how it works:

Contributors identify data out in the wild online, and contribute small index files with some pointers to where the data is hosted, and some other details indicating how to merge it with the rest of the project’s data format. There’s no need to download any of the data, only find where the CSV file or web service lives and how to get to it. The technique for this is neat in its simplicity, more on this later.

It sounds weird to think something as basic as address data could be so fascinating and exciting. Most people in the geo community understand the potential impact of projects like this on our industry, but let me review for the uninitiated why this is cool.

Why care about boring addresses?

Address data is what makes almost any map useful: it connects our human-friendly identifiers for places into real locations on the ground. Almost everything that consumers do with maps these days has to do with places of interest: Foursquare checkins, Instagramming, turn-by-turn directions. Without connecting the places as we know them to actual map coordinates a computer can understand, we don’t have many useful mapping applications.

There are existing APIs and resources out there to build mapping applications that require addressing and geocoding, but none of them are open to build on. They’re proprietary systems that either have unfriendly licensing structures for use, or are costly to use. Having to pay money for a high quality geocoding service like Google’s isn’t crazy or surprising — building universally searchable and uniform address databases is insanely expensive and hard. Building good geocoding systems is one of the perennial pains in the ass of the geospatial problem set, so it’s understandable that when someone solves it, they’d want to charge for it.

There is the OpenStreetMap project, the free and open map database for the globe, which has tons of potential as a resource for geocoding. By a quick estimate, the OSM database contains something like 50 million specific address points for the globe. But its license is not compatible with most commercial requirements for republication of data, so developers looking for an open resource have had to look elsewhere. There’s still no good worldwide, open resource for address geocoding that app developers and mappers can use with no strings attached. (OSM’s license and its “friendliness” for commercial use has a long history of debate and argument in the community. It’s complicated. I’m not a lawyer.)

Simple data, big problem

The data that composes a postal address is pretty straightforward: house number, street name, city, admin boundary, postal code. That set of 6 properties gets you to a fixed coordinate on the Earth in most places with organized addressing schemes. Pretty simple, right?

But addressing systems are non-standard, vary widely with geography, and are actually non-existent in many countries. The data literally carpets the developed world and comes in dozens of shapes and formats, so bringing it all together into a consistent, unified whole to create a platform for applications is a huge deal.

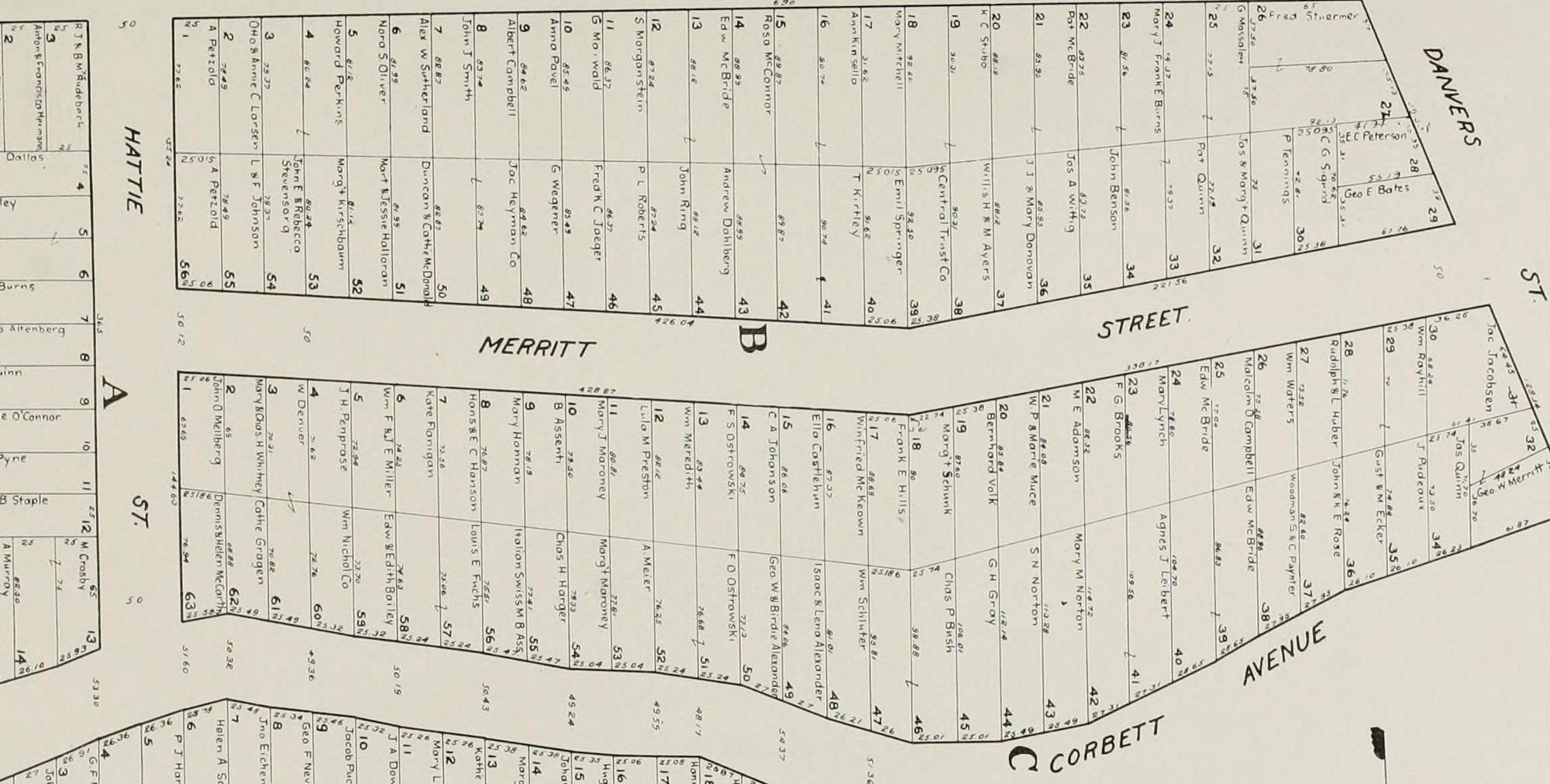

In the US, for example, one of the biggest challenges is that there isn’t a single standardized structure for the data, and even worse, no single “owner” of address data. Sometimes data’s maintained at the county level, and sometimes the city level. One county’s GIS division will manage it, and in another it’s the E911 system manager. Then you have the challenge of finding the actual data files. It’s becoming commonplace for municipalities to publish this stuff online, but it’s far from universal. To get data for some (especially rural) counties, you better be ready to take a hard drive down to the property appraiser’s office to get the data, or pay them to burn you a CD.

To me this is where the OpenAddresses model gets interesting. The project is bringing a powerful capability for building a massive open dataset, a distributed network of contributors, and focusing their resources around a common goal. Creating a central place around which the contributors can mobilize and gradually accrete data into a larger and larger whole, that’s the unique angle to this project. Anyone with enough time and energy can go chase down hundreds of datasets, but it’s much easier when a group with a defined mission can divide and conquer — intersecting the open source contribution model with a data production line. It’s not just a platform for aggregating this data into a single database, it’s a petitioning system to start the process of tracking down the data, and to advocate for it to be made open if it currently isn’t publicly available.

Building the glue

The OpenStreetMap method of contribution is one where contributors are manually finding, converting, and adding data to a separate database. For addresses, this strategy makes ingesting the individual datasets and the thousands of updates per year a huge pain. OA takes a different approach. Instead of manually finding and merging all the datasets together, the main OA repository is a huge pile of index files that function as the glue between all the disparate sources out on the web and a centralized core. It’s an open source ETL system for all flavors of address datasets. People go out and find all the building blocks, and OA is the place where we write the instructions to put them all together.

The project isn’t only the data. It’s tools for working with the data, resources for teaching local advocacy for acquiring the data, and a system of ETL “glue” to bring the sources together to build a platform for other tools and creative mapping projects. Go over to the project and check it out. If you know where some address data is for your neighborhood, dive in and contribute to the effort.