Annals of the Former World

March 15, 2016 • #

I majored in geography in college and always liked earth sciences. I dabbled a bit with classes that were related, but not core to geography study — your basic geology courses and a class in geodesy. One of the classes I took called “Geology of the National Parks” had an applied approach to explaining the foundations of geology. Something about hopping from Katmai to Yosemite to the Everglades made me see geology as more than rocks and minerals. I loved the massive scope and scale of the Earth’s 4.5 billion years. Normally anything with a magnitude starting with a B or T is intangible (distances in deep space) or minuscule (numbers of molecules in a human body). But when talking about rocks, rivers, continents, strata, sediments — these things are very tangible and static, at least in passive observation. A year is a long time at the human scale, but a blink on the geologic. When comparing human and geologic timelines, it takes a while for this to sink in.

I’ve never read anything on the subject of geology. I previously enjoyed John McPhee’s The Control of Nature, and had Annals of the Former World on my reading list after browsing some of his other work. It’s a tome, but I decided to download it on my Kindle and give it a shot.

The book is a Pulitzer Prize-winning collection of 4 books independently researched, written, and published over the course of 20 years starting in the late 1970s. It’s an incredible piece of nonfiction writing, with just the right balance of well-researched science, facts and figures, storytelling, and narrative1. The author tells a geologic history of the North American continent by way of the I-80 corridor across the lower 48 from New York to San Francisco, studying roadcuts and outcrops along the way. Each piece paints a picture of a slice of geologic science, with an emphasis on different landforms and processes. McPhee does an excellent job exposing the deep vocabulary of the geologist without being overwhelmingly technical. He’s traveling with (and quoting) scientists, and the book pushes 700 pages, so there’s no need for brevity.

In each section he splices together a healthy dose of history with scientific explanations of geologic processes. Each part contains a historical timeline of notable events, discoveries, or personalities that made breakthroughs in the science. Some of my favorite bits included foundations of what we know about Earth’s dynamism today, and the battles fought to get there in the scientific discoveries of the 18th and 19th centuries.

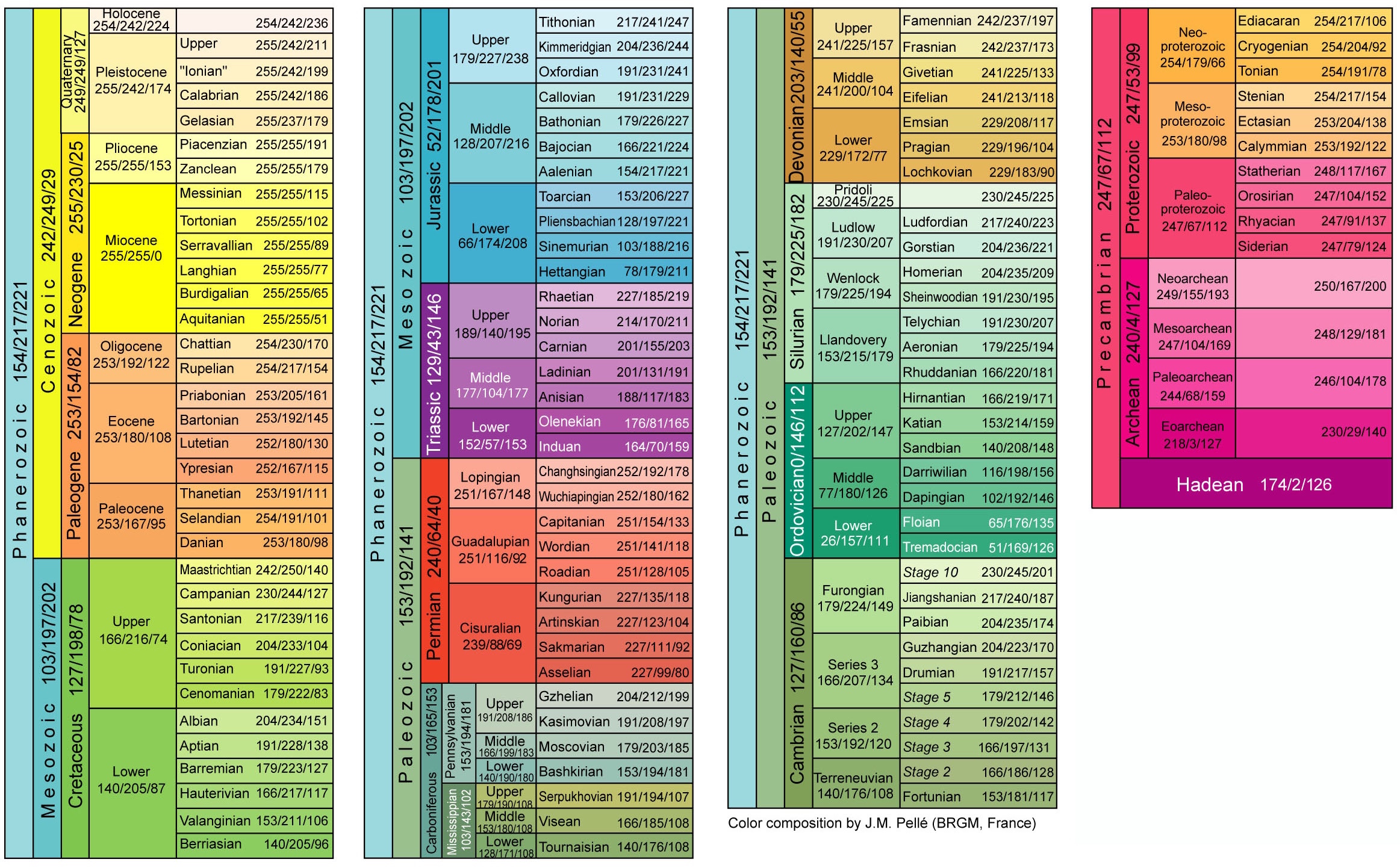

By the end of the book I was just beginning to get comfortable with the order and structure of the geologic time scale. The terms are so numerous that it takes repition to remember which came first, which age is within which epoch, and so on. Precambrian, Eocene, Devonian, Permian, Pennsylvanian, Proterozoic, Hadean, Ordovician — I had to have the trusty time scale at hand for constant reference.

Basin and Range starts things off with a study of the geologic province of the same name, mostly coinciding in the US with the state of Nevada. The expanse lies between the Great Salt Lake and the Sierra Nevada, with rolling folds of hills and valleys.

This section lays the foundation for modern geology by covering the work of two pillar figures: James Hutton and Charles Lyell. Hutton was a Scot that studied in the 18th century, and is known as the “father of modern geology”. As uncontroversial as rocks sound, it’s telling to keep in mind the context in which Hutton was publishing his work:

“Hutton published his Theory of the Earth in 1795, when almost no one doubted the historical authenticity of Noah’s Flood, and all species on earth were thought to have been created individually, each looking at the moment of its creation almost exactly as it did in modern times.”

Making claims that the Earth was billions of years old was as blasphemous to the scientific community of the era as Darwin’s work on evolution. Hutton’s theories of uniformitarianism didn’t stick in 1795. It wasn’t until years later that Lyell took Hutton’s original theories and popularized them in the 1800s with his own Principles of Geology. And Darwin, by the way, was heavily influenced by the work of both geologists:

“Voyaging on the Beagle, he was enhancing his sense of the slow and repetitive cycles of the earth and the giddying depths of time, with Lyell’s book in his hand and Hutton’s theory in his head. In six thousand years, you could never grow wings on a reptile. With sixty million, however, you could have feathers, too.”

In each of the book’s parts, McPhee is traveling with a different geologist in the field. In Basin and Range he’s following Ken Deffeyes, a specialist in the topography, mineral deposits, and stratigraphy of the region, on a mission to locate its abandoned silver mines and hunt unextracted ore using techniques not available during the 19th century mining boom. Most metal deposits have hydrothermal origins. Superheated water from deep underground melts and collects trace metals, makes its way upward through fissures in the rock, and precipitates them out in seams near the surface. As McPhee writes, “a vein of ore is the filling of a fissure. A map of former hot springs is remarkably close to a map of metal discoveries.” I’d love to check out some mining data and compare with geologic maps.

With the primitive theories of deep time and continental movement established in part one, part two, In Suspect Terrain, takes us to the Appalachians in the east. This part focuses mostly on the mountain-building, volcanism, and erosion that created the “suspect terrain” of Appalachia. From geologist Anita Harris we begin to understand the processes and results of glaciation, the most ruthless of Earth’s erosive forces. When the Wisconsinan ice sheet covered the continental US all the way south to Kentucky, it left scars and remnants scattered all over the country from Indiana to New York and up into Canada. The ice pulverized rock from the Adirondacks into gravel and powder and eventually carried it toward the Atlantic, depositing it as Long Island, which is made almost entirely of glacial deposits. The spine of the island is the ice sheet’s terminal moraine, and from there to the south shore is the outwash plain. It’s amazing how much of the country north of Tennessee is covered with topography resulting from the Ice Age glacial sheets. The pockmark lakes covering Ontario, Quebec, Minnesota, and Wisconsin are the “kame and kettle” landscape created by the grinding ice. An interesting statistic: Canada’s ponds, lakes, and streams hold a sixth of all fresh water on Earth.

McPhee peppers his writing with great little anecdotes that make the abstract scientific bits more real. For example: the millions of pool tables and chalkboards made from the slate of Pennsylvania’s Martinsburg formation metamorphosed from shale which was once silty mud on the bottom of the Ordovician ocean, 440 million years ago. I’ll definitely think of this every time I play pool from now on.

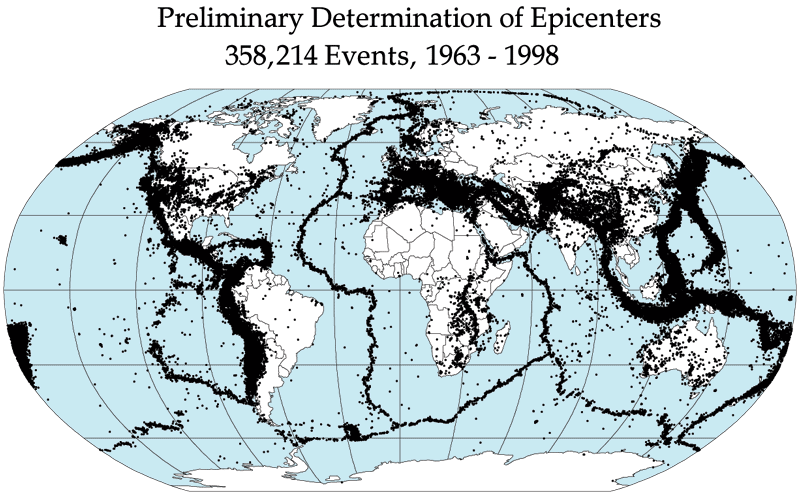

In Suspect Terrain introduces the final formation of plate tectonic theory in the 1960s. Nuclear proliferation in the 1950s had governments investing in seismic monitoring stations all over the world to feel for blast shocks. As a side effect, geologists detected and recorded earthquakes on a global scale, over the course of several years. Tossing those records on a map gives you a clear picture of the eggshell-like plates of crust, with thousands of vibrations marking the slip and slide of the plates against one another.

Part three, Rising from the Plains, takes us to the Rocky Mountains in the company of Wyoming native David Love. This part contains probably the least science, and instead substitutes some excellent tales of Love’s upbringing on his family’s isolated ranch in central Wyoming. In the early 20th century Wyoming was still very much the frontier, sparsely populated with little industry until the coal and uranium mining businesses boomed in the middle of the century. I love the title’s double meaning — Love and the Rockies formations he studied both spring from the eastern Wyoming flatness. The stories of his family roots hammer home how inhospitable and disconnected the West still was at the time.

This chapter dives into the region’s volcanic origins. With Yellowstone Park, it’s one of the most visible examples of hotspot geology in the world. Mountain building is covered in depth here, also, giving some context to how the Rockies built up, and how erosion has broken them and created the sedimentary structures of the outwash plain. The limestone layers in the high Rockies leave record of the Paleozoic ocean that once covered that part of the continent, and lifted only during the last 80 million years, which as McPhee points out is only “the last three percent of time”. Tidbits like this drill home just how deep deep time is. This bit about the Grand Canyon seems almost impossible:

The Colorado River, which has only recently appeared on earth, has excavated the Grand Canyon in very little time. From its beginning, human beings could have watched the Grand Canyon being made.

The origins and primary mission of the US Geological Survey are also covered in Rising from the Plains. The USGS mapped the expanses of territory acquired during the first half of the 19th century to catalog the nation’s resources, and as a result produced some of the original map data still in use through various public sources today2.

The final installment aims to explain the origins of California and the Pacific coast, aptly titled Assembling California. The first point covered is the concept of “exotic terranes”, landmasses that move across oceans and suture themselves onto other continental bodies through subduction faulting. The Sierra Nevada formed this way, a Japan-like archipelago riding the Pacific plate across the ocean and colliding with the Nevada shorelines in the Jurassic. With great effect once again, McPhee explains how terranes come together:

Ocean floors with an aggregate area many times the size of the present Pacific were made at spreading centers, moved around the curve of the earth, and melted in trenches before there ever was so much as a kilogram of California. Then, a piece at a time—according to present theory—parts began to assemble. An island arc here, a piece of a continent there—a Japan at a time, a New Zealand, a Madagascar—came crunching in upon the continent and have thus far adhered.

Faults are fractures in the crust formed around plate boundaries, and covered in depth in this chapter. California’s San Andreas fault complex is a strike-slip transform fault, and one of the most well known to Americans. His story of California begins at Mussel Rock on the San Francisco peninsula, right where the San Andreas enters the Pacific.

The Smartville Block formation that makes up the bulk of California formed on the ocean floor — an ophiolite. There are other similar “ophiolitic” formations on the Earth, so the book includes travels to Cyprus, another ophiolitic complex similar to what prehistoric California may have looked like. Since geologists study how things were, traveling to far flung places with similar structures can transport them to the past. I got a healthy lesson in prehistoric geography from this book. I bookmarked several pages with map renderings of Gondwanaland, Laurasia, and the Tethys Ocean to get my bearings.

Natural history is a subject I don’t read enough of. This book is an incredible piece of writing in general, regardless of format or genre. Like all of McPhee’s articles, essays, and other books I’ve read, this one is right up there with the best nonfiction. If you enjoy long form writing, I highly recommend Annals of the Former World for those interested in science.

-

McPhee is well known for his literary nonfiction, just look at his bibliography. ↩

-

The USGS has a tool to browse its fantastic historical archive of topographic maps. ↩