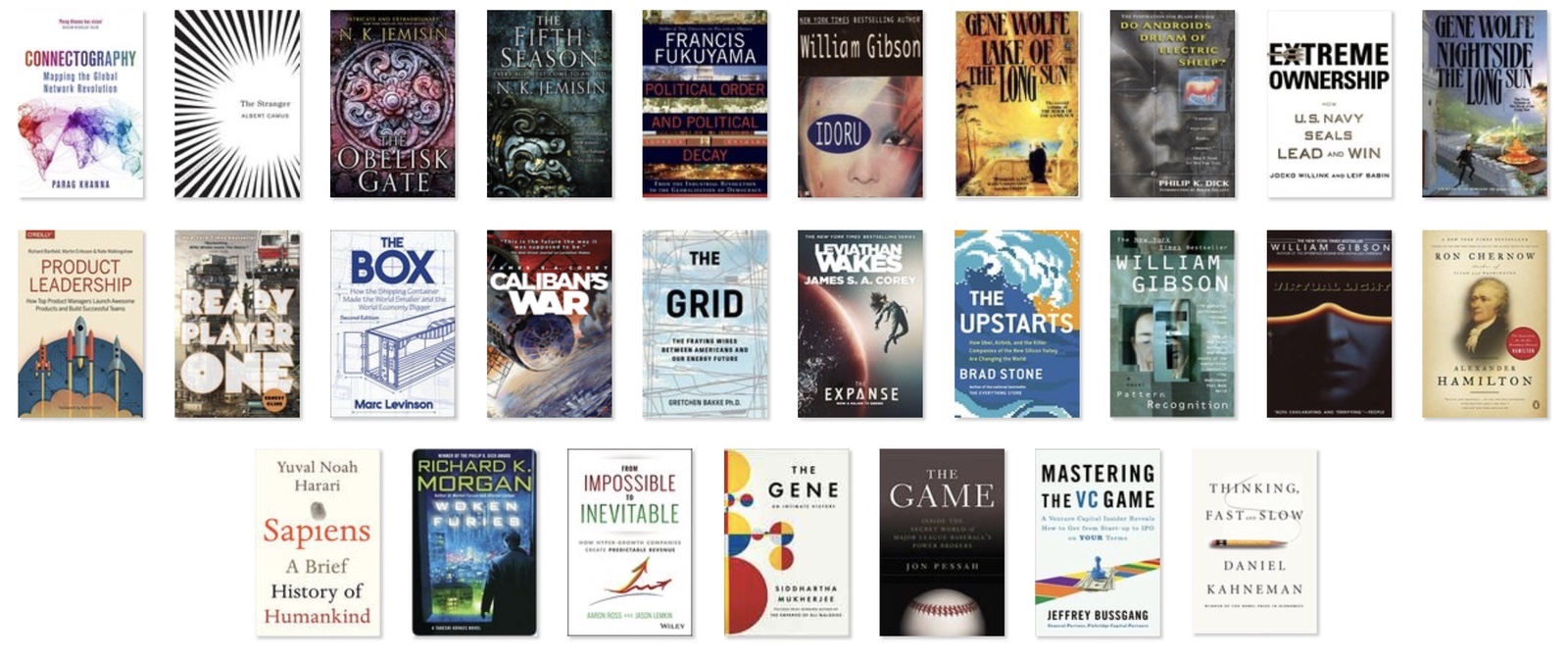

Books of 2017

December 28, 2017 • #I didn’t realize how many things I’d read this year. Looking back at the list, I enjoyed all of them. Here’s a snapshot of my favorites from 2017.

Political Order and Political Decay — Francis Fukuyama. 2014.

This is Fukuyama’s second volume in his treatise on political systems. Last year I read the excellent first part, Origins of Political Order, which chronicles the first forms of human organized societies and tracks the evolution through to the French Revolution. This part picks up where that left off up to modern governments. I had so many thoughts reading this one, and hundreds of Kindle highlights to revisit. It was deep enough to warrant its own blog post, so I’ll hold off here on diving in further and leave it for a future post. I’ll just say that I think these two volumes should be textbooks in college political science classrooms.

The Fifth Season and The Obelisk Gate — NK Jemisin. 2015, 2016.

The first two parts of the Broken Earth trilogy, this story is the most surprising, original, thought-provoking works of fiction I’ve ever read. Jemisin’s series has been well-reviewed, but I knew nothing about it going in other than its apocalyptic setting.

It’s set in the Stillness, a beyond-inhospitable place where people live in tiny communities banded together to survive the earth’s hostile “fifth seasons”. Due to some undescribed past event, the earth experiences these periodic cataclysmic weather, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes. In the Stillness, there is a minority class of people called Orogenes with a mutant power of “orogeny”, essentially like The Force for manipulating earth, giving them the ability to create (or negate) earthquakes. Their counterparts are the Guardians, mysterious people who exist to control and suppress the Orogenes with their own special abilities to quell orogeny. Within this creative, mysterious world that Jemisin’s built, the reader gets to experience a captivating story unfolding to explain the mystery of what happened to this earth. Along the way is a plethora of commentary on race, class, politics, and survival that’s executed so subtly many readers may never even notice. But the story itself is so engaging I ripped through books 1 and 2 in a week.

In summary I’d say my favorite thing about it is its fantastic weirdness. I found myself thinking about it even when I wasn’t reading it — a bar for me that’s rarely surpassed even with great fiction. I’ve been recommending it to everybody, and continue to do so here. Just read it.

Ready Player One — Ernest Cline. 2011.

As I started reading this one, there was some groan-inducing corniness with the unending references to 80s culture and video games. Once I lightened up though, it was a fun, fast read. When I found out they’re making this into a huge-budget film next year, my first thought was “this’ll make a way better movie than a novel.”

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? — Phillip K. Dick. 1968.

This has been on the reading list for years. I finally got around to reading it before the release of Blade Runner: 2049. It was more enjoyable than I expected, but didn’t explore its themes very deeply. Both Blade Runner films present a more interesting exploration of humanity and consciousness, with their thin lines between humans and replicants.

The Gene: An Intimate History — Siddhartha Mukherjee. 2016.

It’s hard to recall many specifics since this one was early in the year, but I was engrossed in this one for a few weeks. It begins with the early discoveries in genetics by Mendel with his fruit flies and covers the entire history of the science including controversial subjects like eugenics, gene therapy, and other forms of genetic engineering.

The Grid: Infrastructure for a New Era, Gretchen Bakke. 2016.

It took some effort to get through the beginning of this one — a bit politically charged and opinionated when what I was looking for was a more comprehensive background on how the current power grid works. It’s well known that the current systems of power generation and distribution through the electrical grid are insufficient and under threat by many modern, distributed, renewable forms of energy. We’re not there yet with wide enough usage of solar, wind, tidal, and other generation methods. This book outlines how the current grid system works, the political machine behind why it works that way, and what likely needs to change if renewables are to be harnessed efficiently at scale. It was informative with just the right depth of technical background to satisfy what I was interested in.

Alexander Hamilton — Ron Chernow. 2005.

Chernow’s epic was the only biography on my list this year. Hamilton was a fascinating guy. He’s probably tied with Franklin for “most interesting Founding Father”. One of the takeaways I had from this book wasn’t specific to Hamilton but rather the time and political climate in which he lived. When people talk about the post-2000 era political environment as the most divisive, hostile time in our nation’s history (not that it isn’t plenty pointlessly divisive), they’re overlooking the shaky early years of the country’s formation, not to mention the Civil War era. During the year of the Constitutional Convention and the following half decade Hamilton served as the first Treasury Secretary, many of the governance structures we take for granted today were controversial and unproven. Thanks to his Federalist Papers arguing the case for strong central government to hold together the tenuous connections between states, and his advocacy of using (small and reasonable) debt to finance economic growth, the first two decades of the United States were prosperous, even though there was significant political upheaval, which the book chronicles in depth.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind — Yuval Noah Harari. 2011.

Best work of nonfiction I read in 2017. Not in a long time have I done so much highlighting and note taking with a book.

It’s an account of human history and evolution from the Stone Age to today. Harari begins by tracing where along the path of primate development that Homo sapiens diverged from the other species of early humans like Neanderthals. His thesis is that Sapiens came to dominate (and possibly eliminate) all other rival species through a distinguished ability to cooperate in large numbers — hundreds or thousands in cooperation rather than dozens. He argues that humans owe this capability for mass shared interest to our ability to create and “believe in” fictions or myths. Whereas other primates could only cooperate in tight-knit familial or band-level groups, Sapiens developed the capacity for creating shared myths: religions, governments, currencies, and more. I found it absolutely absorbing and am looking forward to rereading it soon.

Leviathan Wakes and Caliban’s War — James S.A. Corey. 2011, 2012.

During the summer I got into this: a fun, fast-paced series called The Expanse. It’s your classic space opera — big in scope, full of plot and action, and enough political intrigue to get interesting without getting so complicated as a “Game of Thrones in space”. It’s got a clever, semi-realistic setting in which people have spread throughout the solar system on the back of improved propulsion technology. But it stops well short of light speed travel and other wild concepts. There’s an interesting political dynamic where groups of people that have spread out beyond Mars to stations in the asteroid belt or distant moons of Jupiter and Saturn (known as “Belters”) have a strained relationship with Mars and Earth, who also have their own issues with one another. Against that backdrop a group of rag tag survivors end up thrown in the crossfire.

The Box — Marc Levinson. 2006.

Like a lot of nonfiction these days, this one was too long, but I did find parts of it interesting. In March I listened to Alexis Madrigal’s fantastic Containers podcast, an audio documentary on global economics and trade through the lens of shipping containerization. The Box is sort of like the history textbook version — an informative but somewhat dry account of how we went from breakbulk shipping everything (meaning longshoremen loading individual items piece by piece into ship’s holds) to modularized, automated shipping using standardized containers. What TCP/IP did for packetizing computer information, containers did for physical “stuff”.

Woken Furies — Richard K. Morgan. 2005.

This is the last part of the Altered Carbon trilogy, which I started last year. I felt this was the weakest of the bunch in terms of storytelling, but found it to have some of the most interesting ideas of the whole series. What I said last year about the first two parts mostly holds true here, but the overall plot felt a bit strained and had too much to accomplish to tie up the loose ends.

My favorite concept was the idea of “DeComs”. The book is set on Harlan’s World, the oft-mentioned home planet of Takeshi Kovacs. He joins up with a band of people who roam an uninhabited continent to find and decommission rogue AI-controlled robots — remnants of a past conflict gone haywire. His crew makes a living trekking out and battling the machines to “DeCom” them for cash. I have so much fun reading each subsequent idea or cyberpunk concept Morgan throws out there. With the new series coming to Netflix soon, I hope I have time to revisit part one beforehand. I really enjoyed that one.