Enterprises Don't Self Serve

December 11, 2020 • #In the wake of Salesforce’s acquisition of Slack, there’s been a flood of analysis on whether it was a sign of Slack’s success or failure to grow as a company. It’s funny that we live in a time when a $27bn acquisition of a 7-year-old company gets interpreted as a failure. I’d consider it validation for their business that a $200bn company like Salesforce makes their largest acquisition ever on you. Broadly, it’s a move to make Salesforce more competitive with Microsoft as an operating system for business productivity writ-large.

One likely driver of selling now vs. later was the ever-expanding threat from Microsoft’s fantastic execution on Teams over the few years. Slack saw Microsoft’s distribution and customer relationship advantage, and that they’d have a beast of a challenge peeling away big MS customers. This sort of “incumbent” position in the enterprise is one of the strongest advantages Microsoft has, and they’ve been savvy in playing their cards to feed off of this position.

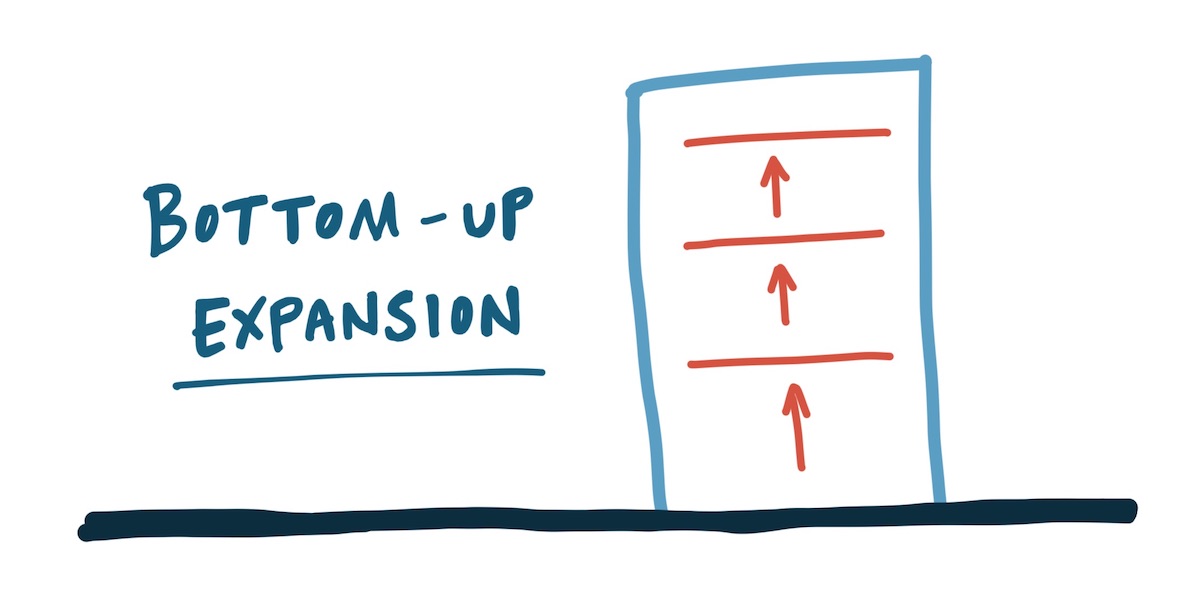

As a new entrant to the enterprise software space, Slack’s bottom-up product strategy has been one of their key advantages that fed their hypergrowth since 2014. The relentless focus on product quality drove viral adoption within user groups inside of organizations. Classic land-and-expand: get teams to adopt for themselves, and weave your way from that beachhead into the rest of the organization, with an eventual (often reluctant) official blessing from IT departments. The product-led growth (PLG) model (of which Slack was an early success story) allows new entrants to serve users first and foremost, sliding in under the radar of corporate buy-in inside companies: “shadow IT”, as it’s known.

Within large companies, self-service and a product-led approach can get you a long way, as Slack and many others have demonstrated. But at a certain size you hit friction points with growth inside large accounts. Enterprise customers rarely adopt software with zero engagement from product makers. But Slack and other PLG successes have been able to push deeper than previously thought possible with hands-off, sales-free tactics.

Former founder and now-investor David Sacks wrote a great Twitter thread on this topic (also discussed on the All-In Podcast), reacting to Slack’s lateness to implement a sales organization:

1/ Ok since you asked, here are my reactions to the Slack deal and @levie comments to the effect that “the idea that workers would someday choose all their own tools was always a fantasy... Best product doesn’t always win, you also need the biggest sales force.” My thoughts: https://t.co/ZYdaf9XvaF

— David Sacks (@DavidSacks) December 3, 2020

“Enterprises don’t self serve”

There’s no question that product-led is the way to go to get validation, traction, and growth, and that it’s still instrumental to building horizontal customer footprint. Sacks’s point is that Slack didn’t handle the enterprise scaling requirements early enough (they now are).

Bottom-up is great for top-of-funnel customer acquisition (Sacks says “lead gen”), but starts to falter as a growth driver at some scale. The trick in architecting a hybrid product-led vs. sales-led dichotomy is finding where and when in the lifecycle to transition growing customers from one to the other. What the PLG movement has done for SaaS companies is carry customer expansion further into companies than before. The likes of Slack, Atlassian, and Twilio carried themselves to enormous scales on the back of a PLG, self-service strategy.

Why does PLG decelerate?

Why would an enterprise company (or one that’s grown their use of a product to enterprise-scale penetration) not be able to self-serve the larger deployment? Why couldn’t a product company rely on self-service once a company’s usage grows to that point? It seems reasonable that if a customer scaled to a couple hundred users that the continued expansion would be an easy justification; if it’s working, why not keep expanding?

There are a few related reasons why relying on customers to serve themselves slows down at scale:

- In large companies, individuals are no longer able to make decisions — champions for a product (that may already be using it in their team) need to build consensus across a diverse group of stakeholders to justify expanding

- Too many cats need to be herded to get a deal done — see item 1, often a stunning number of heads need to be convinced, justified to, and won over; corralling the bureaucracy is a whole separate project unrelated to the effectiveness or utility of the product

- Rarely no individual “buyer” — user can’t purchase product, purchaser has never used product; incentives for each stakeholder working at cross purposes (one is looking to complete a project, one is looking to cut budget, one is looking to impress the press, etc etc)

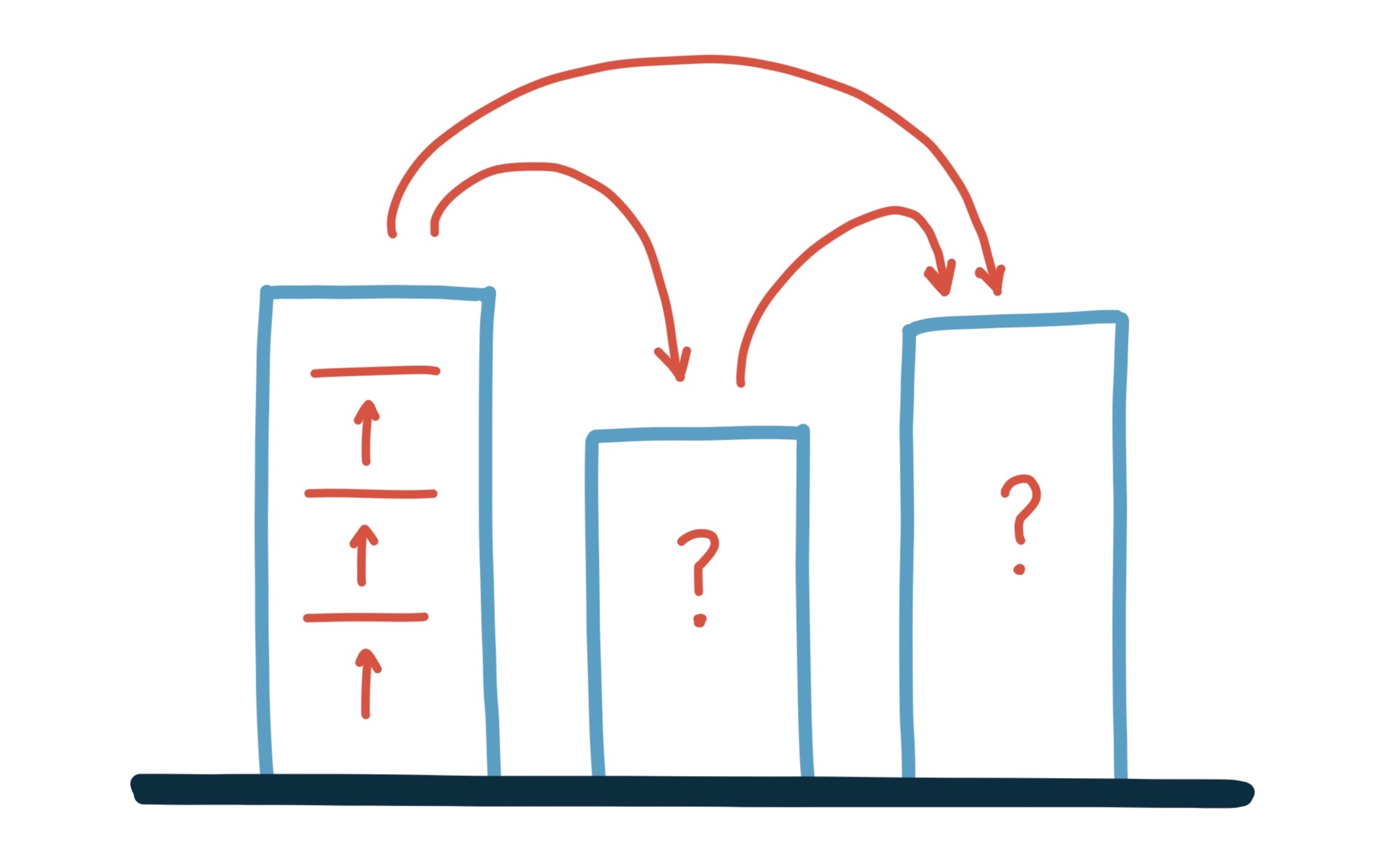

- If you have a champion, they have a day job — And that job isn’t playing politics with accounting, legal, execs, IT, and others; there’s no time for the customer to play this role for you I can speak from experience on all dimensions of this. In the early days of a bottom-up product, landing that big logo and watching them grow looks like this — you’re growing seat count and things look to be taking off:

Watching it happen is magical, especially if you’ve got an early product and/or small team. You’re building product you think is useful, and you’re being validated by watching it weave its way up into a company with a household name.

But you eventually discover that true enterprise-scale adoption looks more like this:

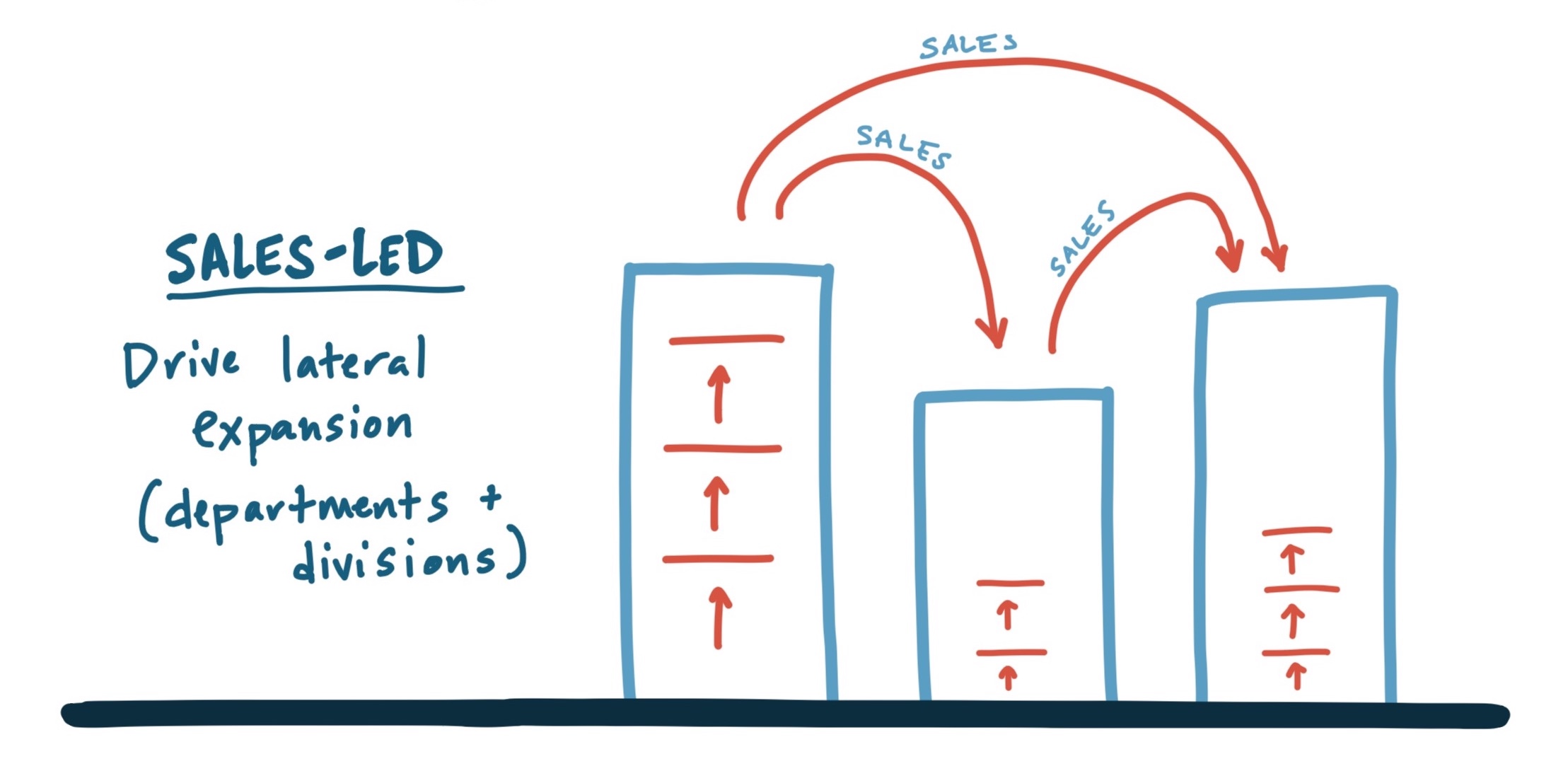

The customer you thought you were growing wasn’t truly the whole enterprise, but only a department or division1. In many (most?) national- or international-scale companies, bridging to neighboring departments is effectively selling to a whole new customer. Sure, the story of your product’s impact from adjacent teams’ use cases is helpful, but often the barriers between these columns are enormous.

What you need is some fuel to help jump the gaps.

Enter your sales team

The reason for the sales team is primarily to coordinate and communicate with the stakeholders described above the on behalf of the buyer.

There are unicorn enterprise customers out there where you’ll find a champion willing to saddle this burden of selling your product to themselves — sometimes a particularly aggressive or visionary IT leader, or exec — but this is a rarity. You can’t and shouldn’t rely on this existing in most organizations.

On the surface this thought runs counter to a lot of recently popular ideas on product-led growth. But what Sacks is claiming in his thread doesn’t invalidate product-led, bottom-up as a strategy — in fact he says the opposite.

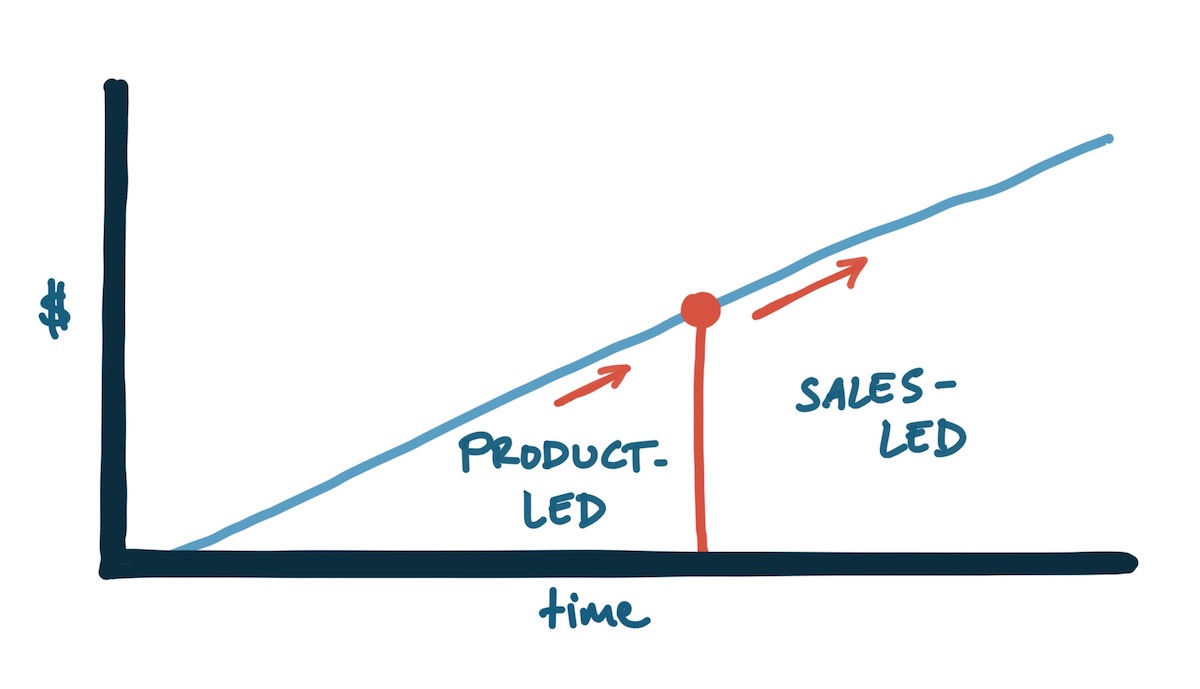

What it does say is that the go-to-market shouldn’t be a binary methodology: either you’re bottom-up / product-led OR top-down / sales-led. For many B2B SaaS companies, the ideal system design is optimizing for product-led evolving into a sales-led approach when a customer reaches a certain stage of the lifecycle.

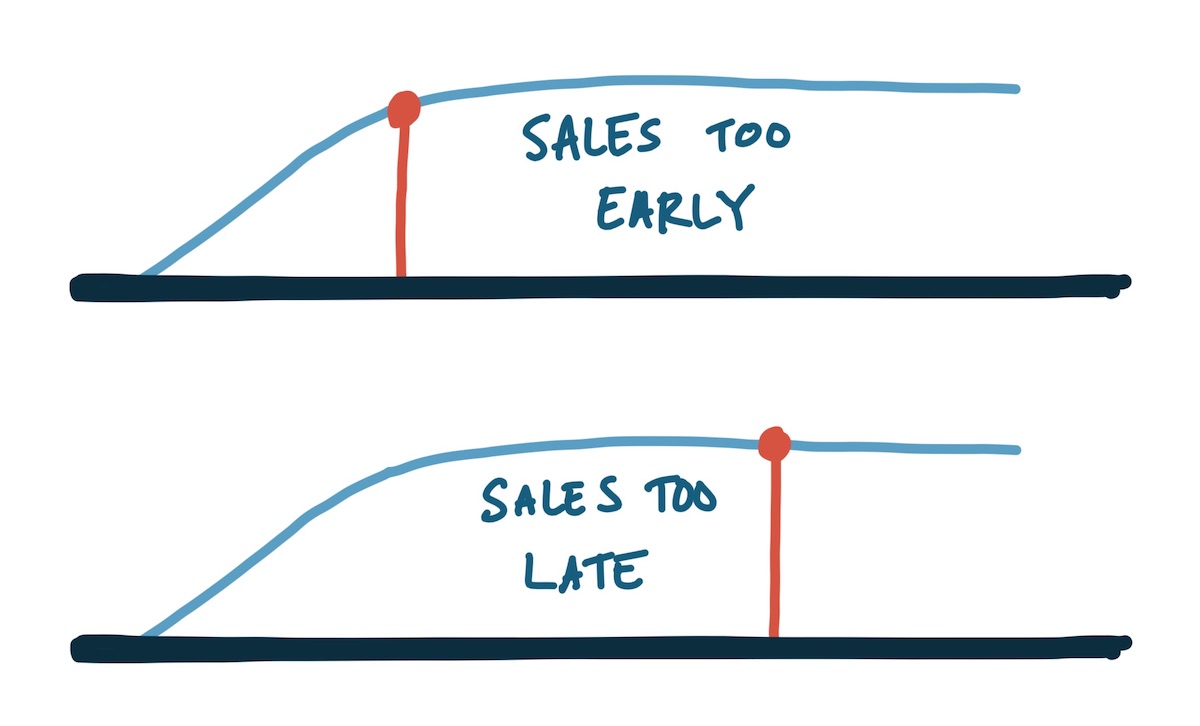

Even for teams that understand the dynamics of both methods, the hard part is finding the right place in the cycle for the methodology to flip. If one set of tactics is largely owned by the product, design, and marketing teams (PLG), and the other owned by sales and customer success teams (SLG), then without proper experimentation, management, and cultural behavior reinforcement, it’s possible that one of those teams leans too far beyond the transition point.

This continuum is, of course, not fixed for all time or all companies. And those transition points are a lot more fuzzy in reality than in a chart.

PLG is growing in effectiveness over time, so the optimum transition stage from PLG to SLG is moving rightward for many types of products. A number of factors could cause this phenomenon. There are more and more companies opting for a PLG approach, but I think this is a response to changes in customer behavior more than it’s a modifier of customer behavior (though those effects move both ways). Things like technical comfort, the prevalence of self-service solutions in consumer technology, ease-of-use as a table stakes expectation, a wider competitive market for tools, and the sophistication level of technology expanding tremendously over the last 10 years are all moving parts that contribute to self-service becoming more widespread.

-

The more hands-off you are in early usage and ramping up, the less you often know about the specifics of the customer. Is it an intern leading a pilot project? Is it a real, funded initiative? Often hard to tell if you’re “auto-scaling” on a PLG strategy. ↩