Hardy Boys and Microkids

The Soul of a New Machine

by

The Soul of a New Machine

by

- Shelves: history, technology, business

- ISBN: 9780316491976 (Goodreads)

- Format: Kindle

- Buy on Amazon

Physicians hang diplomas in their waiting rooms. Some fishermen mount their biggest catch. Downstairs in Westborough, it was pictures of computers.

Over the course of a few decades dating beginning in the mid-40s, computing moved from room-sized mainframes with teletype interfaces to connected panes of glass in our pockets. At breakneck speed, we went from the computer being a massively expensive, extremely specialized tool to a ubiquitous part of daily life.

During the 1950s — the days of Claude Shannon, John von Neumann, and MIT’s Lincoln Lab — a “computer” was a batch processing system. Models like the EDVAC were really just massive calculators. It would be another decade before the computer would be thought of as an “interactive” tool, and even longer before that idea became mainstream.

The 60s saw the rise of IBM its mainframe systems. Moving from paper tape time clocks to tabulating machines, IBM pushed their massive resources into the mainframe computer market. S/360 dominated the computer industry until the 70s (and further on with S/370), when the minicomputer emerged as an interim phase between mainframes and what many computer makers were pursuing: a personal, low-cost computer.

The emergence of the minicomputer should be considered the beginning of the personal computer revolution. Before that, computers were only touched by trained operators — they were too complex and expensive for students, secretaries, or hobbyists to use directly. Minis promised something different, a machine that a programmer could use interactively. In 1964, DEC shipped the first successful mini, the PDP-8. From then on, computer upstarts were sprouting up all over the country getting into the computer business.

The DEC PDP-8

The DEC PDP-8

One of those companies was Data General, a firm founded in 1968 and the subject Tracy Kidder’s book, The Soul of a New Machine. A group of disaffected DEC engineers, impatient with the company’s strategy, left to form Data General to attack the minicomputer market. Founder Edson de Castro, formerly the lead engineer on the PDP-8, thought there was opportunity that DEC was too slow to capitalize on with their minis. So DG designed and brought to market their first offering, the Nova. It was an affordable, 16-bit machine designed for general computing applications, and made DG massively successful in the growing competitive landscape. The Nova and its successor sold like gangbusters into the mid-70s, when DEC brought the legendary VAX “supermini” to market.

DEC’s announcement of the VAX and Data General’s flagging performance in the middle of that decade provide the backdrop for the book. Kidder’s narrative takes you inside the company as it battles for a foothold in the mini market not only against DEC and the rest of the computer industry, but also with itself.

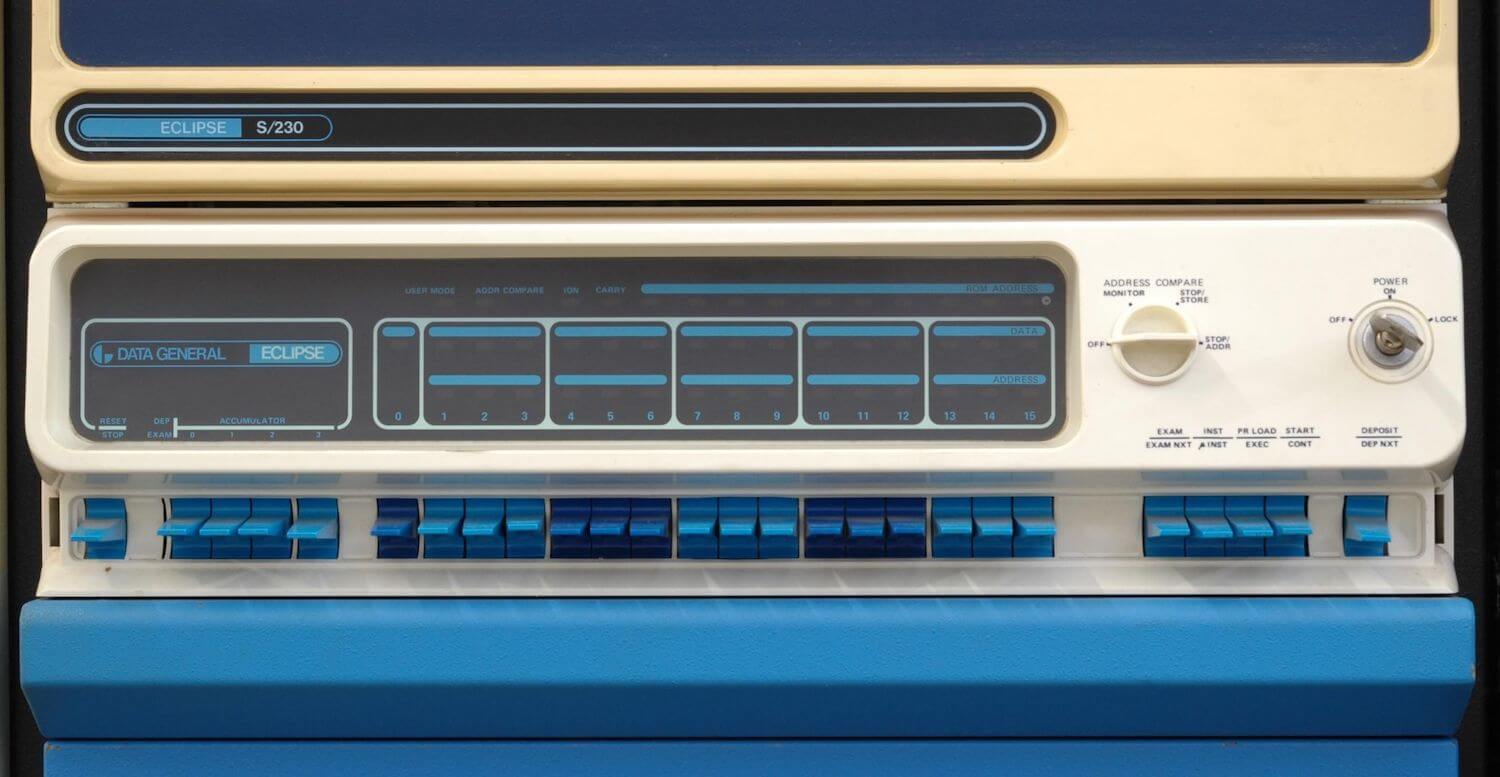

The VAX was set to be the first 32-bit minicomputer, an enormous upgrade from the prior generation of 16-bit machines. In 1976, Data General spun up a project codenamed “Fountainhead,” their big bet to develop a VAX killer, which would be headquartered in a newly-built facility in North Carolina. But back at their New England headquarters, engineer Tom West was already at work leading the Eclipse team in building a successor. So the company ended up with two competing efforts to create a next-generation 32-bit machine.

Data General’s Eclipse S230

Data General’s Eclipse S230

The book is the story of West’s team as they toil with limited company resources against the clock to get to market with the “Eagle” (as it was then codenamed) before the competition, and before Fountainhead could ship. As the most important new product for the company, Fountainhead had drawn away many of the best engineers who wanted to be working on the company’s flagship product. But the engineers that had stayed behind weren’t content to iterate on old products, they wanted to build something new:

Some of the engineers who had chosen New England over FHP fell under West’s command, more or less. And the leader of the FHP project suggested that those staying behind make a small machine that would solve the 32-bit, logical-address problem and would at the same time exhibit a trait called “software compatibility.”

Some of those who stayed behind felt determined to build something elegant. They designed a computer equipped with something called a mode bit. They planned to build, in essence, two different machines in one box. One would be a regular old 16-bit Eclipse, but flip the switch, so to speak, and the machine would turn into its alter ego, into a hot rod—a fast, good-looking 32-bit computer. West felt that the designers were out to “kill North Carolina,” and there wasn’t much question but that he was right, at least in some cases. Those who worked on the design called this new machine EGO. The individual initials respectively stood one step back in the alphabet from the initials FHP, just as in the movie 2001 the name of the computer that goes berserk—HAL—plays against the initials IBM. The name, EGO, also meant what it said.

What proceeded was a team engaged in long hours, nights and weekends, and hard iteration on a new product to race to market before their larger, much better funded compatriots down south. As West described it to his team, it was all about getting their hands dirty and working with what they had at hand — the definition of the scrappy upstart:

West told his group that from now on they would not be engaged in anything like research and development but in work that was 1 percent R and 99 percent D.

The pace and intensity of technology companies became culturally iconic during the 1990s with the tech and internet boom in that decade. The garage startup living in a house together working around the clock to build their products, a signature of the Silicon Valley lifestyle. But the seeds of those trends were planted back in the 70s and 80s, and on display with the Westborough team and the Eagle (which eventually went to market as the Eclipse MV/80001). Kidder spent time with the team on-site as they were working on the Eagle project, providing an insider’s perspective of life in the trenches with the “Hardy Boys” (who made hardware) and “Microkids” (who wrote software). He observes the team’s engineers as they horse-trade for resources. This was a great anecdote, a testament to the autonomy the young engineers had to get the job done however they could manage:

A Microkid wants the hardware to perform a certain function. A Hardy Boy tells him, “No way—I already did my design for microcode to do that.” They make a deal: “I’ll encode this for you, if you’ll do this other function in hardware.” “All right.”

If you’ve ever seen the TV series Halt and Catch Fire, this book seems like a direct inspiration for the Cardiff Electric team in that show trying to break into the PC business. The Eagle team could represent any of the scrappy startups from the 2000s.

It’s a surprisingly approachable read given its heavy focus on engineers and the technical nature of their work in designing hardware and software. The book won the Pulitzer in 1982, and has become a standard on the shelves of both managers and engineers. The Soul of a New Machine sparked a deeper interest for me in the history of computers, which has led to a wave of new reads I’m just getting started on.

-

In those days, you could always count on business products to have sufficiently boring names. ↩