Managerial Leverage

August 5, 2019 • #Andy Grove is widely respected as an authority figure on business management. Best known for his work at Intel during the 1980s, his book High Output Management is regularly cited as one of the best in the genre of business books. After having it on my list for years and finally reading it earlier this year, I’d wholeheartedly agree. It’s the best book out there about business planning, management, and efficiency, still just as pertinent today as it was when it was first published in 1983.

Its relevance more than 30 years later attests to the universality of its value. I’ve mentioned before here my personal interest in understanding first principles approaches to thinking over derivative systems typically touted by the self-help and business publishing community. The book’s extreme practicality and information density falls in line with what you’d expect from an engineer like Grove — light on the fluff and “case study”-type stuff that permeates and inflates page counts of other business books.

I’ve written here before about a couple of specific topics from the book — about Grove’s perspective on meetings, and on the concept of “modes of control” — but I wanted to give some more space to the book overall, as I believe it’s one of those rare pieces of core reading material on which hundred of other works are based.

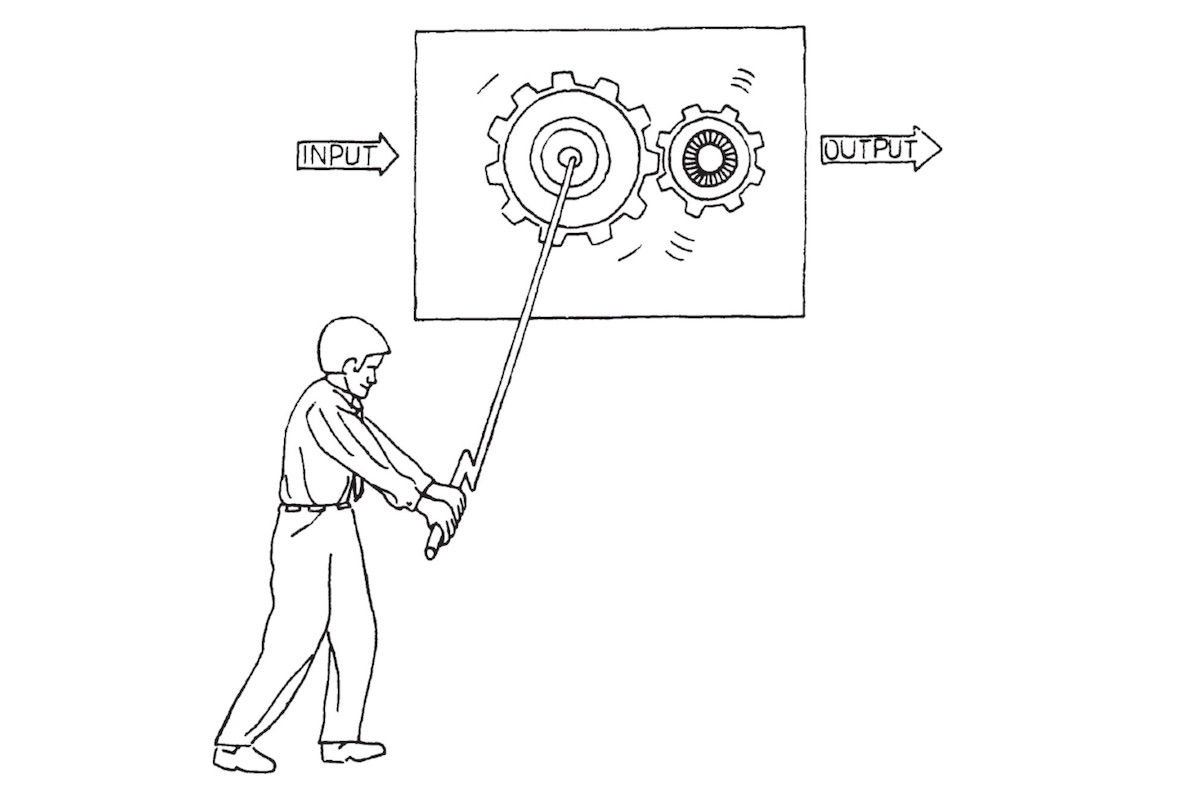

The thesis he lays out is simple in principle: a business is a machine, the people and processes are its parts, with inputs (human effort, ideas, work) and outputs (its products and services). To develop a high output system, you have to peel apart its internal components, inspect how they interface with one another, and create a management infrastructure throughout that enables high leverage. Throughout the book’s chapters he touches on the stables of a manager’s workload: planning, meetings, making decisions, reporting, oversight, training, and more. What’s truly important isn’t any one of these particular components, though, it’s in the efficiency of the connections between them. In the analogy of the business to a machine, effective management is the design of the parts, the connections between them, and the lubrication to avoid slippage.

I’ll point out here that the book’s value is not limited to those that manage people. If you manage any system or procedure at all you’ll get value out of it. In fact, it’s useful to anyone that wants to understand what makes their organization tick and where they might fit into the machinery.

Creating Clarity from Abstraction

One of the driving factors that’s created a cottage industry around business processes, teamwork, and strategy (an industry that’s generated thousands of how-to books on the theme) is that the modern era of “knowledge work” requires working in so many abstractions. In the good old days of industrial production, the inputs, outputs, and stages in between were manifest in physical systems you could watch working together. Grove recognizes this point early1 (emphasis mine):

Of course, the principle of work simplification is hardly new in the widget manufacturing arts. In fact, this is one of the things industrial engineers have been doing for a hundred years. But the application of the principle to improve the productivity of the “soft professions” — the administrative, professional, and managerial workplace — is new and slow to take hold. The major problem to be overcome is defining what the output of such work is or should be. As we will see, in the work of the soft professions, it becomes very difficult to distinguish between output and activity. And as noted, stressing output is the key to improving productivity, while looking to increase activity can result in just the opposite.

Too many businesses sit down and “strategize” by developing high-altitude mission statements, corporate principles, and annual goals. There’s nothing wrong with these things, but they ultimately aren’t granular enough to become actionable by individual team members. Aligning around a well-articulated output at each employee’s level is critical to avoiding the “busyness” syndrome that plagues so much of the modern workplace. What’s missing is a tool to bridge this gap between high-minded mission statements and employees, one that arms them with actionable targets they can point at and measure progress on — enter OKRs.

Objectives, Results, and Measurement

A key concept articulated in High Output Management, one that’s been adopted widely today, is the Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) framework. It’s clear from the way Grove articulates it that he didn’t see OKRs as some kind of brand-building opportunity with an intent to sell this idea to the business community; he merely saw it as a way to give the company a circulatory system throughout to keep its teams in alignment on output. Like many of the ideas in the book, he has a succinct style of communicating these ideas that make them seem patently obvious, with a clarity that’s easy for anyone to comprehend.

Anyone in the knowledge work space (which is most of us) has seen this all over our organizations. Without the focus around the outcome — What exactly are we making? What do we want that to do for us? Why? — any organization can dissipate much of its energy in simply performing activities, the way an inefficient machine gives off much of its energy as heat from friction. The mission then is to make sure any activity performed at any level is clearly tied to output that stacks up with the organization’s top-level expectations.

The venture investor John Doerr, most known for his work with Kleiner Perkins and investments in Amazon, Google, Netscape, and other early internet companies, was an employee and colleague of Grove in the Intel days. I recently read his Measure What Matters, a book on the concept of OKRs and how they’re employed in various modern businesses. My problem with that book was that it’s simply a retelling of the core principles laid out in High Output Management, with most of the pages devoted to the “see how it works for organization X?” type of commercial trying to sell you on the idea of OKRs. That might be a good communication style for a certain type of reader, but I’d rather have the core building blocks and let me do the imagining of how it might impact my own work and organization. There are tons of other books and blog posts out there about OKRs, but I’d point anyone looking into them to High Output Management as a resource.

At the core OKRs are a great system because of how little “system” there really is. They’re intended to get a bunch of diverse people in a hierarchy working as a well-oiled machine, with the strongest emphasis on keeping the machine and it’s components focus on shared, agreed-upon outcomes. It’s about having the diligence to create a stacked set of priorities and goals, mutually agreed on, that cascade from the top down into the ranks. A well-designed OKR process should create a universe where everyone in the organization can point directly to their objectives, and any colleague can see the wiring up and down from there to the OKRs of others.

Writing as Reporting (and Thinking)

It’s partially my personal style, but I’m a huge believer in the idea of writing as a tool for status reporting, intra-office communication, and teamwork. Not only does writing things down create a log of someone’s idea or design concept, it’s a fantastic medium for forcing critical thinking. Jeff Bezos has famously required agendas for meetings at Amazon to be written up as long form proposals. This forces rigor in having focused meetings with thought out discussion topics. No one will spend time writing up a document if they don’t truly believe in it or haven’t thought it through, which saves everyone the wasted time of discussing poorly-considered ideas. The act of writing something down also forces you as the generator of an idea to ruminate on its implications, think about how to articulate it, and to create an element of knowledge to leave as an institutional guidepost for future coworkers thinking about related ideas.

Grove approaches managerial reporting and planning from a similar angle. While he highly values passing informal conversation in maintaining time-sensitive communication, he respects writing as a tool for clear thinking2:

I have to confess that the information most useful to me, and I suspect most useful to all managers, comes from quick, often casual verbal exchanges. This usually reaches a manager much faster than anything written down. And usually the more timely the information, the more valuable it is.

So why are written reports necessary at all? They obviously can’t provide timely information. What they do is constitute an archive of data, help to validate ad hoc inputs, and catch, in safety-net fashion, anything you may have missed. But reports also have another totally different function. As they are formulated and written, the author is forced to be more precise than he might be verbally. Hence their value stems from the discipline and the thinking the writer is forced to impose upon himself as he identifies and deals with the trouble spots in his presentation. Reports are more a medium of self-discipline than a way to communicate information. Writing the report is important; reading it often is not.

This same logic applies to so many things in business — the final version of a report, design spec, marketing strategy, or budget isn’t where all the value lies; the final output document is what enforces the discipline of that business process. The requirement to come away with the “Budget 2020.xlsx” file forces us to run through the planning process thoroughly. If done well, we only need to look at the document as a quarterly gut check. The planning process itself makes us think through priorities, objectives, and where we want to focus.

Add It to the Library

There’s a lot more excellent material in the pages of High Output Management than I can cover in a single blog post. My paperback copy sits on my shelf in my office and is scribbled all over. I pull it out regularly to cite paragraphs or reference things for my own communication within the company. It’s one of my first recommendations to anyone looking for a book on business or productivity.