Neumann on Schumpeter on Strategy

October 20, 2020 • #There’s a myth in popular culture that associates “being an entrepreneur” with “making a lot of money.” But do they, if compared to a world where an entrepreneur did the same job in the employ of someone else?

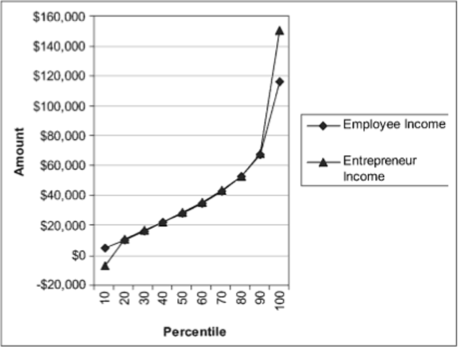

In this post, Jerry Neumann references a chart from Scott Shane’s The Illusion of Entrepreneurship that tells a much more realistic story of what creating your own business means financially:

The vast majority make the same, if not less than, their non-self-employed peers, at least until you’re into the 80th+ percentile where the incomes balloon, those massively successful entrepreneurs who create something much more valuable, well beyond their own level of input. Political economist Joseph Schumpeter described this as one of inputs and outputs. In both cases — where a person is a founder versus a contributor in another company — they’re an input to the system, contributing in the same capacity toward profit regardless of their status:

In a market economy, at equilibrium, Schumpeter says profit gets competed away. By profit he means “surplus” profit: the money a company makes if its inputs are priced correctly. Crucially this includes the cost of money adjusted for the risk the investor is taking. That is, you can’t increase risk and say “look, now there’s a profit.” That profit is the cost of the money used in the business.

Neumann points out an interesting insight around why entrepreneurs start their own businesses. It may be that the popular understanding of what drives a founder is financial, that their primary motivator is to make more money. But here’s a shocking statistic: that 81% of founders have no desire to grow their business:

Shane notes that the median revenue of an owner-managed firm is $90,000 and that 81% of founders have no desire to grow their business. This is because most founders are “just trying to make a living, not trying to be a high-growth business.” And they “start firms in industries where there are a lot of firms already in operation” and “report they have no competitive advantage.”

It turns out that independence is one of the largest drivers for people to work for themselves, not to get rich (though I’m sure most would agree that they’d like that, too, just maybe not enough to push that much harder than working as an employee). Quoting Shane again:

“The real reason most people start businesses…has nothing to do with wanting to make money, to become famous, to better their own communities, to seek adventure, or even to improve the world. Most people start businesses simply because they don’t like working for someone else.”

He goes on to tie this back into how it drives typical business strategy. Not all “startups” (in the loosest definition of the term — “independent company” rather than “SV company building software”) have the same underlying motivations driving their creation, so should not be compared in economic terms on the same dimensions.

If you polled government civil servants, regulators, or funding organizations, everyone would agree that new business formation is something to be encouraged and enabled. But if so much policy is developed with a definition of “startup” that you read in the news (your Ubers and WeWorks and Airbnbs and other hypergrowth compatriots, driven by market expansion and dominance rather than simply personal independence), then they’re only framing the infrastructure around a small (actually, by quantity, tiny) subset of companies. Refining the popular understanding of what “starting a business” actually looks like on the ground would go a long way to helping make it easier to do, and give your average person a better appreciation for what the motivators really are.

Everyone I know who runs a small business would be first in line to tell you: if you want a bigger paycheck, don’t start your own company. If you asked a random person on the street, though, they’ll generally associate “business owner” with “person that makes a lot of money.” I’ve never been one myself (yet), but I have a totally different perspective than this with so many direct relationships with business owners.

If most people had a better understanding of what motivates the founder, how much better could we do at supporting entrepreneurial activity?