In his new book Loonshots, author Safi Bahcall uses the concept of phase transitions to analyze how companies work. When a substance changes phase, like water going from solid to liquid, the same exact substance is forced to take on a new structural form when the surrounding environment changes.

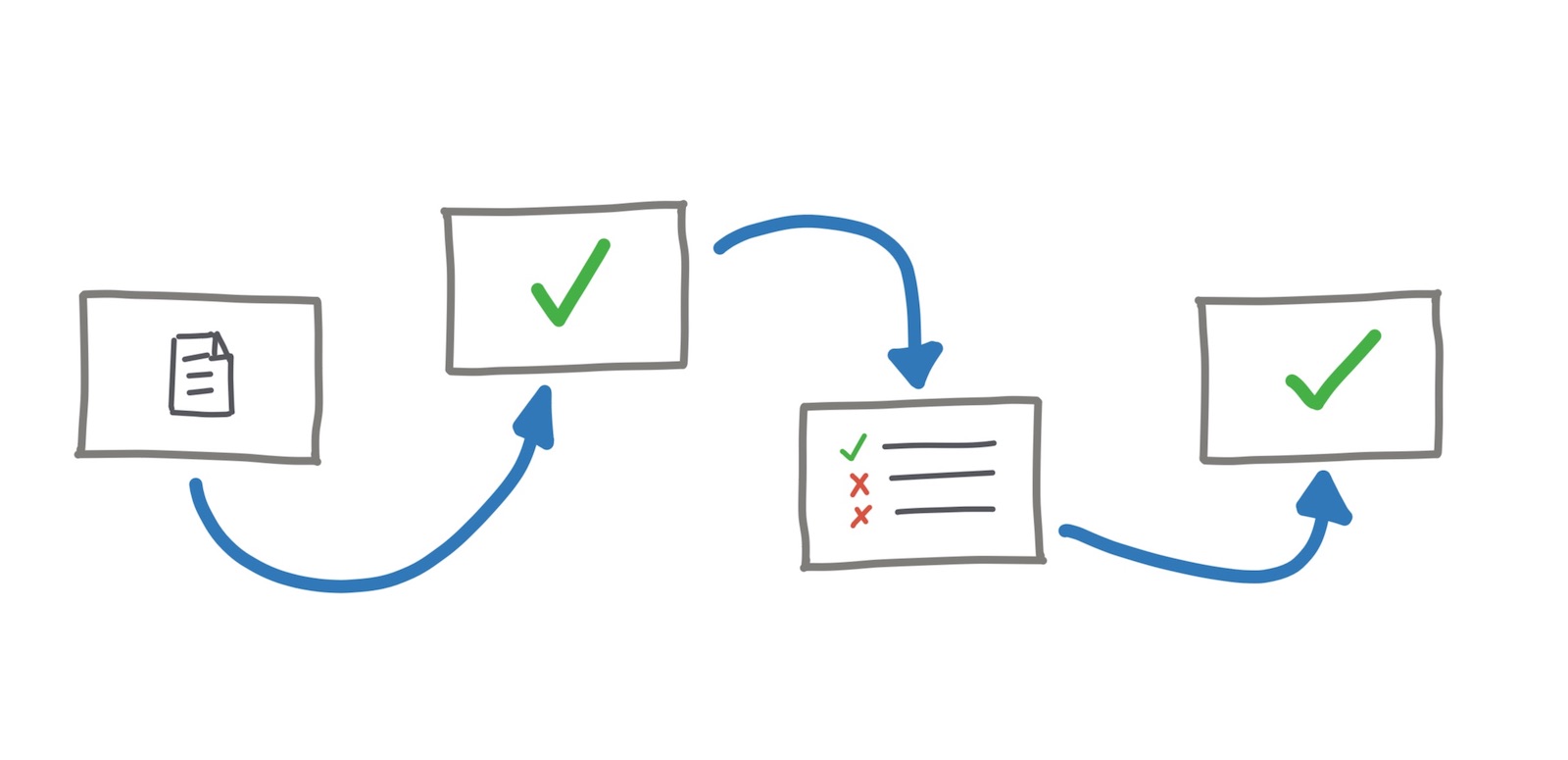

As Bahcall points out in the book, companies exhibit a similar behavior in their inventions and strategy. He contrasts two different types of innovations that companies tend to be built to produce: “P” type innovations, where a company is great at producing new products, and “S” type innovations, where they can stay ahead of the pack by developing new business strategies for the same products. There are many examples presented in the book of both types of innovation done right — Juan Trippe and Pan Am, Steve Jobs, Edwin Land and Polaroid, Bob Crandall and American Airlines — each of them was (or has been) a pillar innovator with a specialty in P or S types.

Being great at a single type works great for a time, until the environment changes too much around you.

In the history of business, there are few examples of organizations able to straddle both phases simultaneously. Early on in the book there’s the example of Vannevar Bush, the engineer that led the historic Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II. The OSRD was legendary for the systems and inventions developed during the war, many of which helped to tip the war in favor of the Allies. From the OSRD wiki page:

The research was widely varied, and included projects devoted to new and more accurate bombs, reliable detonators, work on the proximity fuze, guided missiles, radar and early-warning systems, lighter and more accurate hand weapons, more effective medical treatments, more versatile vehicles, and, most secret of all, the S-1 Section, which later became the Manhattan Project and developed the first atomic weapons.

What makes companies so focused on short term innovation, either in product or strategy? Humans (and organizations) are certainly known to be bad at having a long view of planning and decision making.

It’s a fascinating idea — that a successful, hard-to-kill organization becomes one by having a particular structure, one that can be water and ice at the same time. What Bush figured out 70 years ago was that the organization is what’s important. He focused on making organizations that could make great things, a focus on the process rather than its products:

This bit from a 1990 piece after his death sums it up:

He was an academic entrepreneur who co-founded Raytheon and was a vice president at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who consolidated the school’s reputation as having the nation’s finest engineering program. It’s not just that Bush was a brilliant engineer; it’s that Bush knew how to map, build and manage the relationships and organizations necessary to get things done. He knew how to craft the human networks that could build the technological networks.