The Diminishing Coast

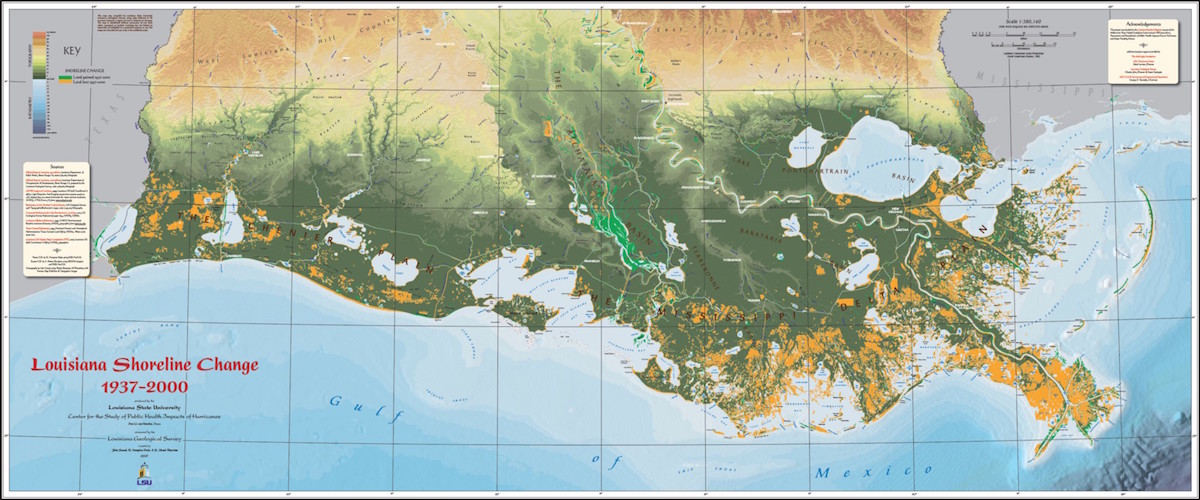

Yesterday I read this fascinating piece on the state of Louisiana’s gulf coast. This slow, man-induced terraforming of the coastline is permanently eradicating bayou communities, and becoming a high-profile issue in the state. One of the author’s contentions is that the misrepresentation of the state’s ever-changing shape on official maps is a contributor to the lack of attention paid to this drastic situation. I love this use of correct maps as an amplifier of focus, to clarify what bad maps are hiding from the general population.

This issue of map miscommunication isn’t isolated to crises like the one happening on the Louisiana coast, it’s inherent in thousands of government-produced official maps both nationally and internationally. Some of the quotes in the article from GIS experts I thought did a good job demonstrating this fact, that old data tells lies:

He pulled up an aerial image of Pass Manchac, the channel between lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas. On both the image and the Louisiana state map, the area appears to be forest. Anyone who has visited the flood-prone town of Manchac, about a 45-minute drive northwest of New Orleans, knows it is surrounded by wetlands. “People see the vegetation and the trees and think it’s land,” Mitchell said.

Where ancient natural processes of erosion and sedimentation collide with human influence — as in the canals, flood control systems, levees, and shipping channels in the bayous of Louisiana — it strikes a highlight through the age and inaccuracy of the maps on record. As a contributor in the article states, the various layers of government-produced data that are generally thought to be relatively static can be decades old:

His experience updating maps with digital tools has exposed how inconsistent existing maps already were. “The topographic layer might have been done in 1956, and the land cover layer was done in 1962, and the transportation came from 1945,” Mitchell said of his findings. “And those are some of the good ones.”

Keeping these sorts of data up to date is a costly affair, no doubt. But with a natural ecosystem as dynamic as that of southern LA, pretending that 50 year old data is good enough is an exercise in denial. The cartographer Harold Fisk created a map series in the 40s (featured in the piece) that shows a historical picture of the natural environment: a 200-mile wide swath of meandering Mississippi riverbed that was once used to spreading its southerly-transported sediment all over the southeast parts of Louisiana’s boot. This was massively disrupted when the Corps of Engineers rigidly fixed the riverbed shape of the river with dike and levee systems, to keep it from straying and affecting the extensive infrastructure and human settlement that runs along the riverfront from New Orleans to Natchez.

As drastic as the situation is, it’s one without a clear solution; it’s an issue of competing priorities, with completely opposite, but critical ends. Fixing the coastline and allowing renewed alluvial deposit to repair the missing land means tremendous impact on Louisiana’s oil and gas industry (one of the largest in the union). Doing nothing and keeping existing man-made infrastructure in place and unaffected means losing land at a lightning pace, not to mention the negative impact to the fishing industry up and down the coast (again, one of the nation’s largest producers). And with every passing year of the Corps’ nonstop work to control the river’s path, the risk of disastrous floods increases.

Last month at a GIS conference in New Orleans, I sat in on a talk given by Allison Plyer from The Data Center, a NOLA non-profit specializing in advocacy around opening and publishing civic map data for all sorts of local issues. She showed some of these maps published earlier this year by ProPublica in their “Losing Ground” series. I highly recommend the ProPublica maps, as well as The Data Center’s projects to showcase the human geography of greater NOLA, particularly their work post-Katrina.

Read the article, it’s a great piece of writing.