The Idea Maze

I ran across this set of lecture notes from Balaji Srinivasan’s “startup engineering” course.

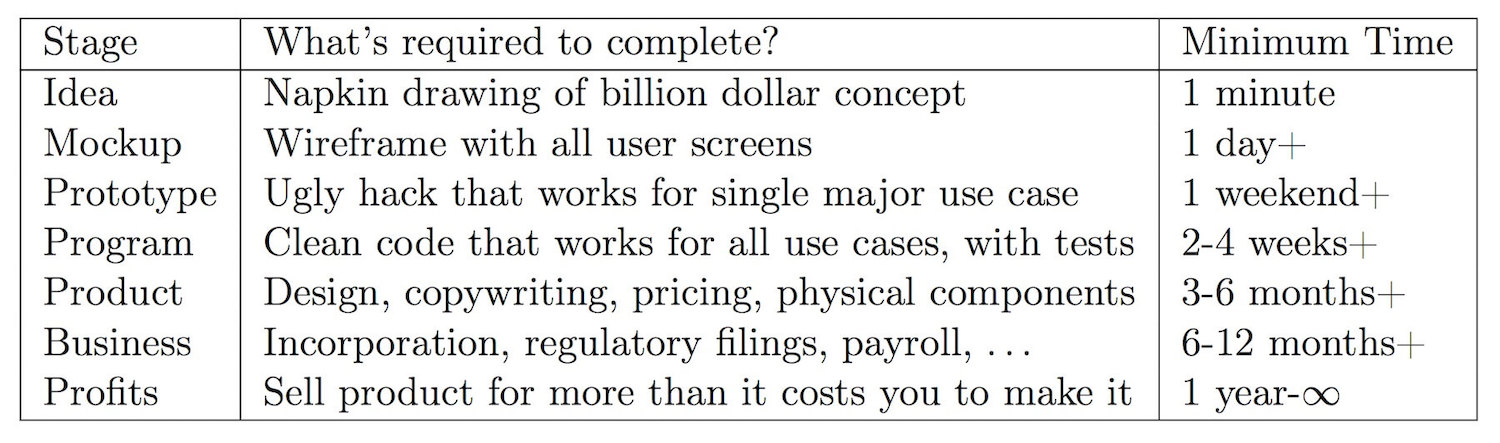

He proposes this format for thinking about the phases a company moves through — from idea to profits:

- An idea is not a mockup

- A mockup is not a prototype

- A prototype is not a program

- A program is not a product

- A product is not a business

- And a business is not profits

You can map this onto the debate between “idea vs. execution” by calling everything below the idea the stage “execution.” In certain circles, especially among normal people not steeped in the universe of tech companies, the idea component is enormously overweighted. If you make software and your friends or acquaintances know it, I’m sure you’re familiar with flavors of “I have this great idea, I just need someone who can code to build it.” They don’t understand that everything following the “just” is about 99.5% of the work to create success (or more)1.

Thinking of these steps as a state machine is a vivid way to describe it. He has them broken out in detail:

When laid out that way it’s clear why it takes such persistence and wherewithal to see an idea through to being a business.

To understand if you have an idea worth pursuing (or even one good enough to be adapted/modified into a great one), it’s a good exercise to simulate the game in your head, to imagine you’ve already moved through a couple steps of the state machine. What are you encountering? If you think of a roadblock, how would you respond? This sort of “pre-gaming” is what separates the best creators and product minds from everyone else. They take small, minimum-risk steps, look up to absorb new feedback, and adapt accordingly2.

Srinivasan calls this phenomenon the “idea maze”:

One answer is that a good founder doesn’t just have an idea, s/he has a bird’s eye view of the idea maze. Most of the time, end-users only see the solid path through the maze taken by one company. They don’t see the paths not taken by that company, and certainly don’t think much about all the dead companies that fell into various pits before reaching the customer.

A good founder is thus capable of anticipating which turns lead to treasure and which lead to certain death. A bad founder is just running to the entrance of (say) the “movies/music/filesharing/P2P” maze or the “photosharing” maze without any sense for the history of the industry, the players in the maze, the casualties of the past, and the technologies that are likely to move walls and change assumptions.

In other words: a good idea means a bird’s eye view of the idea maze, understanding all the permutations of the idea and the branching of the decision tree, gaming things out to the end of each scenario. Anyone can point out the entrance to the maze, but few can think through all the branches.

I remember Marc Andreessen in an interview talking about questioning founders during pitches: if you can probe deeper and deeper on a particular theme to a founder and they’ve already formulated a thoughtful answer, it means they’ve been navigating the idea maze in their head long before being probed by an investor.

It’s worth thinking about how to incorporate this concept into my thinking on future product growth. I think to some extent this sort of thing comes naturally to certain people; the naturally curious ones are doing a version of this all the time, often unintentionally. But what if you could be intentional about it?

-

Not to mention the fact that people are typically ignorant to how often their eureka idea has already been tried or has already gained success because it’s obvious enough to have attracted plenty of others. ↩

-

See Antifragile, Taleb’s magnum opus. An entire book on the subject of survivability, risk reduction, adaptation, and respect for proceeding with measured caution in “Extremistan” (highly unpredictable environments). ↩