The Infinity Machine

An Elegant Defense

The Extraordinary New Science of the Immune System

by

An Elegant Defense

The Extraordinary New Science of the Immune System

by

- Shelves: science, biology, medicine, genetics

- ISBN: 9780062699107 (Goodreads)

- Format: Audiobook

- Buy on Amazon

This one is part book review and part reflection on some personal experience, a chance to write about some science related to a harrowing past experience.

A couple of years ago I had a run in with genetics-gone-wrong, a life-altering encounter with cancer that would’ve gone much differently if I was older or had the run-in in the wrong decade. The short version of that story (which I still plan on writing more about one day on this blog) is that I made it through the gauntlet. A stage IV diagnosis, 6 months of chemotherapy, and 2 major surgeries, and now I’ve been at “NED,” as they say, for 2 years1.

The fine doctors of the Mayo Clinic were able to navigate me through a treatment plan that had to do with genetics, and what’s possible nowadays with modern treatments that rethink the toolbox for cancer.

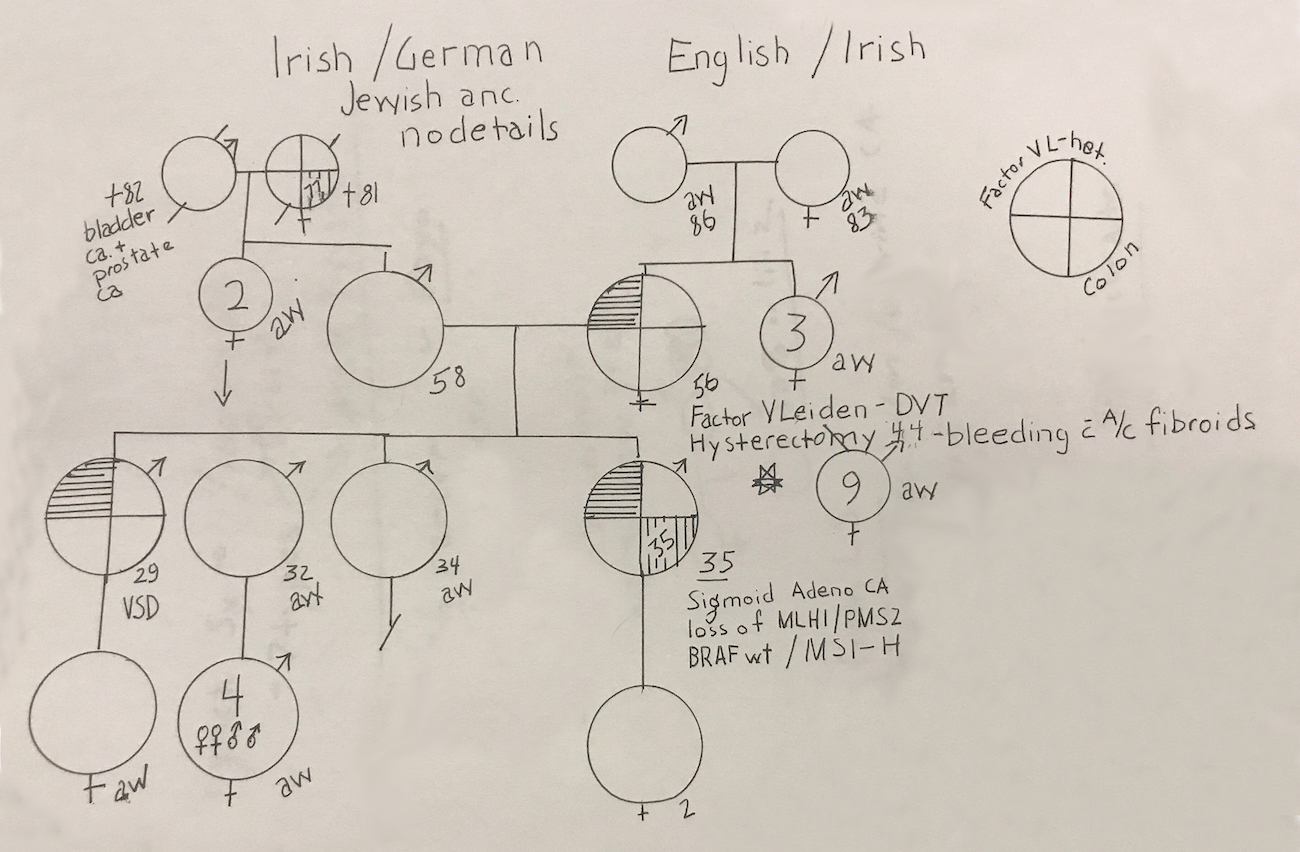

Working with the doctors and genetics team there2, I got a crash-course in Lynch syndrome, an inherited disorder that results in increased risk of developing cancers — specifically colorectal, intestinal, liver, and a few others. To say that Lynch is complex is a massive understatement. The geneticist I met with had to draw diagrams and flowcharts to answer the seemingly simple question “Do I have Lynch syndrome?” (see the image below) To cut to the (strange) point, my cancer expressed Lynch, but not me (see, it’s complicated). This meant we could try something different. Genetic oddities like this can serve as targeting tools for specific drugs.

A testing algorithm for Lynch syndrome (Goodenberger & Lindor, 2011.)

A testing algorithm for Lynch syndrome (Goodenberger & Lindor, 2011.)

Thus began my experience with immunotherapy, a category of wonder drug that’s exploding on the medical scene as a weapon for battling cancer. More on this in a bit, but let’s explore the book and how it relates to all this.

The Elegant Defense

An Elegant Defense investigates the power, and sometimes lethality, of the immune system. Through four separate cases — a patient with terminal cancer, one with HIV, and two with autoimmune disorders — it looks at what happens when immunity works like it should, but also what happens when the system goes haywire. This book isn’t about cancer immunotherapy exclusively, it’s an overview of the immune system in general — the adaptive versus innate immune system, T cells, cytokines, inflammation, and much more. As a primer on the amazing adaptive machinery of human immunity, it’s a top-notch read.

Throughout the book, Richtel uses the analogy of a “peacekeeping force” to describe the immune system, an apt one that I think works well in most of his descriptions. Peacekeeping elements maintain law and order, of course, but sometimes under the wrong conditions, the peacekeepers can incite violence themselves. Instances of “autoimmunity” (any time the immune system inappropriately responds to stimuli by attacking healthy cells) he compares to phenomena like nationalism, xenophobia, or even Nazism — cases in sociocultural systems where what starts off as a “defense mechanism” goes on the offensive. It’s a fitting analogy that helps to make a deeply complex scientific topic accessible to a wider audience.

The highlight of the book was Part II, titled “The Immune System and the Festival of Life.” This section serves up the meat of the story, providing a background on how immunity works, its building blocks, and the history of the science of immunology. B cells, T cells, vaccines, the thymus, inflammation, transplants. Richtel does good work succinctly covering the basics of an incredibly complex system. How did this level of complexity emerge? What is the immune system evolved to respond to?

The Villains

The “Festival Crashers” come in several forms. Bacteria, viruses, parasites, and cancers each bring their own deadly tactics that our immune systems have to learn to defeat. The biggest challenge comes from the fact that these enemies know this and do everything they can to blend in, so the immune system has to identify friend or foe:

Survival depends on knowing what is self and what is alien. The immune system must cope with three major challenges: the variability of bad actors, the central circulatory system that sends rivers of blood throughout our body in seconds, and the need to heal.

And the immune system must do all that without so overheating that it kills us in the process. It walks the most delicate path. It succeeds with the help of peacekeepers so effective that their work could be mistaken for magic.3

Faced with this challenge, the body’s adaptive immune system needs to evolve along with its enemies, to get better over time.

Trainable Defenses

Taleb’s notion of antifragility is on glorious display with the human immune system. His central theory holds that for an antifragile system, stressors, shocks, failures, and challenges increase a system’s abilities over time. The stressors serve as information channels to help the system adapt to future ones. At birth, babies have weak immune systems; their bodies haven’t seen the millions of pathogens they’ll eventually run across. Being exposed in manageable doses to mild illnesses gives a child’s immune system the feedback loop it needs to counter future threats.

But what about completely novel threats? How can it, on first encounter, identify and eliminate threats it’s never seen?

How can your T cells and B cells react to a pathogen they’ve never seen, never knew existed, and were never inoculated against, and that you, or your doctors, in all their wisdom, could never have foreseen? This is the infinity problem.4

It’s my favorite part of the immune system story, the part that’s the closest to the supernatural. Proof of the incredible things the “tinkering” of evolution’s trial and error can develop.

It turns out that the genetic makeup of B and T cells is very different from other blood cells:

The antibody-encoding genes are unlike all other normal genes. Yes, I used italics. Your immune system’s incredible capabilities begin from a remarkable twist of genetics. When your immune system takes shape, it scrambles itself into millions of different combinations, random mixtures and blends. It is a kind of genetic Big Bang that creates inside your body all kinds of defenders aimed at recognizing all kinds of alien life forms.5

The system essentially pre-creates trillions of possible random combinations of genetic codes, creating an archive of “guesses,” keys to locks that could exist, but your body has no idea. Human genetics adapted a way to combat intruders by brute force.

Or if you prefer a different metaphor, the body has randomly made hundreds of millions of different keys, or antibodies. Each fits a lock that is located on a pathogen. Many of these antibodies are combined such that they are alien genetic material—at least to us—and their locks will never surface in the human body. Some may not exist in the entire universe. Our bodies have come stocked with keys to the rarest and even unimaginable locks, forms of evil the world has not yet seen, but someday might. In anticipation of threat from the unfathomable, our defenses evolved as infinity machines.6

It all seems impossible to believe.

A Bit of History

The potential to use the immune system as a controllable disease-fighting arsenal was first observed in the 19th century. In the pre-Germ Theory days of medical treatment, however, there was little hope of physicians figuring out what was really going on. True immunotherapy drugs have only been around since the 1970s, with the development of interleukins, followed by the cytokines (like interferon) and others.

In reading more about the history of immunology as a treatment path for cancers, I ran across the “father of immunotherapy,” bone surgeon William B. Coley. He noticed several cases in which patients with cancers developed unrelated bacterial infections, then had their tumors disappear, so he searched for a link:

Having noted a number of cases in which patients with cancer went into spontaneous remission after developing erysipelas, he began injecting mixtures of live and inactivated Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens into patients’ tumors in 1891.

Coley achieved responses such as durable complete remission in several types of malignancies, including sarcoma, lymphoma, and testicular carcinoma. The lack of a known mechanism of action for ‘Coley’s toxins’ and the risks of deliberately infecting cancer patients with pathogenic bacteria caused oncologists to adopt surgery and radiotherapy as standard treatments early in the 20th century.7

In the days before antibiotics, Coley was bold enough to experiment with intentionally dosing patients with bacteria, with the theory that this was stimulating the immune system to handle the cancer on its own. Though it was much more empirical and experimental than based on scientific theory, it just seemed to work. This kicked off decades of exploration in how the immune system actually worked, and investigation into manipulating it to fight ailments like cancer.

Changing Tactics

One of the patients followed in the book is a guy named Jason, a friend of the author that throughout is in a battle with a vicious case of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. After every form of surgery, radiation, and chemo, he’s eventually put through trials on an immunotherapy, with incredible response that ravages the tumors (or rather, enables his immune system to do so). He gets the same thing that I had 12 doses of, a drug called nivolumab.

My first few months’ experience in treatment was a crash course in understanding the different options available. I was loosely familiar with chemotherapy and radiation, at least as broad techniques for treating the disease. Immunotherapy was completely new. Luckily the research doctors at Mayo are happy to give their patients crash courses in understanding the detailed science behind how the treatments work.

Oncologists are fond of analogies in comparing treatments:

- Chemotherapy is like carpet bombing, or even a nuclear weapon. The tactic is to blow up everything in the area and hope the disease goes with it.

- Contrast that with immunotherapy, which is more like a surgical strike. Find the right target and targeting method, and send in the cruise missile to kill the disease with minimal collateral damage.

Or a better way I like to think about it: compare immunotherapy to code-breaking. Figure out the foe’s patterns and algorithms, then formulate a key that defeats the “encryption.” As mentioned earlier, it’s much like the immune system’s natural solution to the “infinity problem.” But rather than generating those genetic keys, immunotherapies are only assisting the immune system in doing the job its already got the keys for. Cancer cells express proteins that essentially deactivate T and B cells, causing them to ignore the mutated monsters and turn away. All of the “checkpoint inhibitor” drugs like nivolumab function by ignoring these proteins so the immune system can attack.

My genetic history as diagrammed by my geneticist

My genetic history as diagrammed by my geneticist

It’s hard to describe the contrast in treatments without experiencing them (which no one should have to do). My chemo regimen was one called FOLFOX, which was a cocktail of several drugs delivered over the course of several hours, every 2 weeks. I also had Avastin added to the mix for additional factors8. Total all of that up and you’re under a flood of poison flowing through the bloodstream, leaving a trail of side effects like nausea, high blood pressure, terrible cold sensitivity, neuropathy, and brutal fatigue. My age plus excellent anti-nausea meds helped me work through it much better than I’d expected, and without more than mild symptoms. But toxicity builds up from treatment to treatment, so treatment 1 is bad mentally not physically, and treatment 10 is the reverse, since you feel worse, but your anxiety about the process is much lower.

Immunotherapy had zero side effects for me. I’d go and get my 30-minute infusion biweekly (contrast again with chemo’s 3+ hour infusion sessions), and head home as if nothing had happened. It’s wild to go from such a rough treatment process to something actually easier than most routine visits to the doctor.

Emergent Power

The infinity machines within our bodies are marvels of evolution. Understanding better how these machines work can give us deep insights into the complex and powerful emergent order of immunity, with opportunities to harness those T cells in lifesaving treatments. But the autoimmune story is a terrifying display of what can go wrong if we’re not careful. Toying too much with the infinitely complex immune system could result in the deadly overreactions that can kill in minutes.

The field of immunology research is complex, costly, and fraught with risks of exacerbating problems if trial and error isn’t kept in check or if researchers overshoot the target. But I’m personally thankful for the research institutions and pharmaceutical chemists out there on the edge figuring out new ways to understand disease and aid our bodies in doing magic.

-

“No evidence of disease” in the oncologist’s lexicon. Their way of saying “everything we can see is gone.” ↩

-

What kind of institution has a whole genetics division? Mayo Clinic is an incredible place, a marvel of science and patient care. ↩

-

Richtel, An Elegant Defense, p. 55. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 85. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 85. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 89. ↩

-

With the fancier generic name “bevacizumab.” ↩