The Three Laws of Robotics

March 7, 2014 • #This is part two of a series on Isaac Asimov’s Greater Foundation story collection. This part is about the short story collection, I, Robot.

Picking up with the next entry in the Asimov read-through, I read a book I last picked up in college, I, Robot. This is the book that cemented his reputation in science fiction. His works on robots are probably his most well-known. He was an early thinker in the space (he even coined the term “robotics”), and wrote extensively on the subject of artificial intelligence. After reading this again, it’s incredible how much influence a 60 year old collection of pulpy science fiction thought experiments ended up having on the sci-fi genre, and arguably on real-world engineering technical development itself.

I, Robot isn’t a novel, but a collection of 9 short stories, each of which were published independently in several science fiction publications throughout the 1950s. The parts are stitched together within a framing story of Dr. Susan Calvin, the “robopsychologist” that makes appearances in several of Asimov’s robot stories, recounting her experiences with robot behavior working for US Robots and Mechanical Men, from the time of the earliest models to extremely advanced humanoid versions. Fundamentally, I, Robot is a philosophical study of Asimov’s famous Three Laws of Robotics, laws that dictate the allowable behavior of robots and which form the basis of much of his exploratory thinking on the nature of intelligence:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

This simple set of rules form the basis for the stories of I, Robot. The groundwork of the Three Laws lets Asimov ruminate on logical, ethical thought process, and what differentiates the human from the artificial.

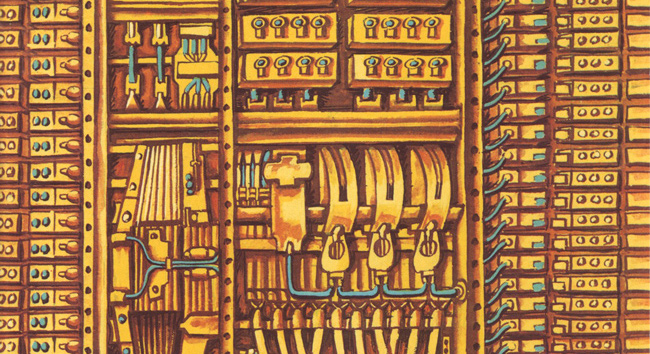

Each story is an analysis of an aspect of robotic technical development. As the stories progress and the technology advances, each plot line underscores elements of human thought taken for granted in their complexity and nuance. In order to poke and prod at the Three Laws, moral and psychological situations are presented to investigate how robots might respond to input, and by extension, how minor variations in inputs could dramatically change response. Asimov’s robots are equipped with “positronic brains“—three-pronged logic processors that weigh every decision against the Three Laws. Upon initial interpretation within the framework of the Laws, each plot’s situation appears to result in a conundrum or violation of the rule set. Asimov’s mystery storytelling then kicks in and invites the reader to deconstruct and solve the puzzle.

My favorite of the stories center around US Robots’ field engineers, Mike Powell and Greg Donovan. They appear in four of the nine stories, and serve as the corporate guinea pigs responsible for putting new robot models through their paces in a variety of settings, from remote space stations to inhospitable planets to asteroids. I loved how the technology always seems to get the better of them, only to have them figure clever solutions by twisting the Three Laws to their advantage. In “Reason”, Powell and Donovan are stuck on a space station with a robot named QT-1 (Cutie), a model with highly developed reasoning abilities. Cutie refuses to obey any of their commands because it reasons that a power exists higher than humans, which it calls “The Master”. They eventually discover that the Master is actually the station’s power source, which Cutie determines is of a higher authority than the stations human operators, as none of them could exist without it. It’s a 2001-esque series of events, though Cutie isn’t quite as insidous as HAL.

“Evidence” introduces the character of Stephen Byerley, a man suspected of being a highly-developed humanoid robot. Dr. Calvin attempts to use psychological analysis to determine if he is man or machine when physical means are exhausted, realizing that if he were truly a robot, he would be forced by programming to obey the Three Laws. But the investigation takes a turn when she realizes that his conformance with the Three Laws may “simply make him a good man”, since the Laws were engineered to model human morals.

In the final story, “The Evitable Conflict”, Asimov even hints at what our modern AIs will look like, with positronic brains embedded in even non-humanoid machines, a 1950s vision of Siri or Watson. These computers of the future are critical in managing the world’s economy, mass-production, and coordination. The computers begin experiencing minor glitches in decision-making that seem to be minor violations of the First Law. But it turns out that the computers have effectively invented a “Zeroth Law” by reinterpreting the First: A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm—making minor exceptions to the First Law to save humanity from themselves. Between Calvin and Byerley, there’s a sense of despair as humanity has given its future over to the machines. Would we be okay dispensing with free will in order to avoid war and conflict? It punctuates the final evolutionary path of robotic development, and provides a nice segue into the Robot novels in the future chronology of his universe.

“Think, that for all time, all conflicts are finally evitable. Only the Machines, from now on, are inevitable!”

I’m interested to see where the path leads as I continue to read more of his work, and to find out how these robot stories interconnect with his wider universe. Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It’s clever, thought-provoking, humorous, and will make you realize how many of our favorite works of science fiction in writing and film owe a tremendous debt to this book.