Upwhen and Downwhen

The End of Eternity

by

The End of Eternity

by

- Shelves: science fiction, classics

- ISBN: 9780449016190 (Goodreads)

- Format: Paperback

- Buy on Amazon

This is part one of a series of essays on Isaac Asimov’s famous Greater Foundation story collection. In this first one I discuss the time travel mystery The End of Eternity.

The prolific science fiction writer Isaac Asimov published an astonishing body of work in his life. Though he’s probably most well-known for his stories, collections, and postulations about robots (and, therefore, artificial intelligence), he wrote a baffling amount speculating on much bigger ideas like politics, religion, and philosophy. The Robot series is one angle on a bigger picture. Within the same loosely-connected universe sit two other series, those of the Empire and Foundation collections. Altogether, these span 14 full novels, with a sprinkling of several other short story collections in between.

In deciding to read all the works in the collection, I first had to choose where to begin. Is the best experience had by reading in the order he wrote them? Or to read them in story chronological order? Trying to figure this out, I naturally ran across the sci-fi message board discussions arguing the two sides, with compelling arguments both ways. I wasn’t sure which had more merit until I read that Asimov himself suggests a chronological approach, rather than in the order of their writing, to lend maximum immersion into the galactic saga. Taking a tip from another reader, I also decided to go a step further and begin with one outside of the main series, but seen by many as a precursor to the other storylines — the 1955 time travel story The End of Eternity.

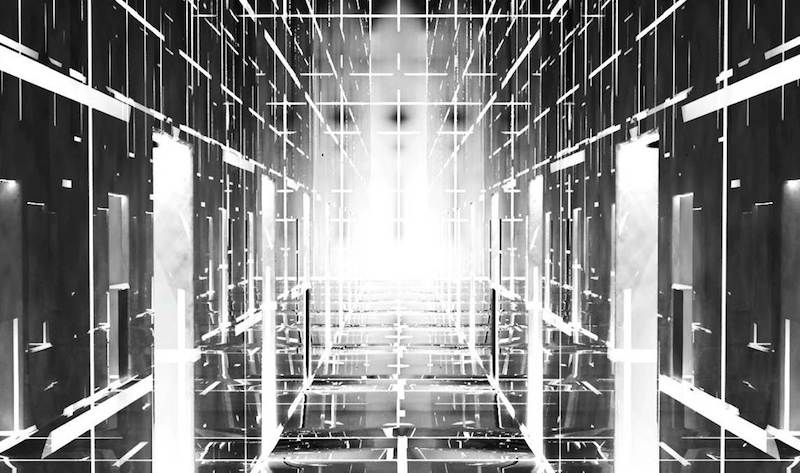

The novel is primarily a mystery-slash-thriller, set in a distant future. The story follows the experiences of Andrew Harlan, a man extracted from Reality and into “Eternity”, a place that exists outside of time where humans called “Eternals” have taken it upon themselves to police the timeline of human existence, altering Reality where necessary to minimize human suffering, and control the flow of history. Eternals are people recruited from various times throughout history for particular desired skills, from the 27th century, all the way up to the 30,000th and beyond. Within Eternity is something of a class hierarchy, with Eternals dividing up the duties: Sociologists use statistics to plot the lives of individuals, Computers calculate the long-term effects of Reality Changes, and Technicians pinpoint the exact moments in time at which to intiate the Reality Change. By traveling time and entering at an exact pre-calculated point, Technicians strive to introduce the “minimum necessary change” to induce a “maximum desired response”. In other words, the smallest modification to Reality possible to create the most positive outcome:

“…He had tampered with a mechanism during a quick few minutes taken out of the 223rd and, as a result, a young man did not reach a lecture on mechanics he had meant to attend. He never went in for solar engineering, consequently, and a perfectly simple device was delayed in its development a crucial ten years. A war in the 224th, amazingly enough, was moved out of Reality as a result.”

Harlan is one of the Technicians, who actually triggers these butterfly effect Reality Changes. Unlike most of the Eternals, he has a fascination with the “primitive centuries”, those of the era before the discovery of time travel in the 24th. He collects artifacts from the 20th and 21st centuries — magazines, books, and other relics of the past to understand what made people tick in the time before Eternity. So Harlan and the other Eternals go about this business, traversing time “upwhen” and “downwhen” along their temporal transit system, shaping history like plastic.

This story contains one of my favorite takes on time travel. It presents a set of rules, obeys those rules, and directly acknowledges the time paradoxes it introduces. The plot itself is set up as a mystery, flinging Harlan into a Twilight Zone-esque narrative, leaving us as perplexed as he is as to what is actually going on, and whether he’s being manipulated by those around him. Eternals are allowed no contact or personal relationship with any “Timers”, people not aware of Eternity and that still exist within the timeline of Reality. Since the reality changes they induce can remove the existence of friends and family from Reality, Eternals are supposed to sever ties with family and forget that they ever existed. Like much time travel-based fiction, keeping tabs on the plot can get confusing, even though there’s a logical framework for how time travel functions in this universe.

For a story written in 1955 (and about as “hard sci-fi” as you can get), I was pleasantly surprised with several scenes that felt like reading a fast-paced thriller, with twists and revelations popping up every few pages for the entire final third of the book. One in particular consists of Harlan entering a point in time he had entered previously, creating the first of several ontological paradoxes that become key plot elements. The characters in the story directly acknowledge these paradoxes, speculate about the effects of an Eternal meeting himself, and even hatch a scheme to save Eternity by intentionally creating one.

The grand experiment of social engineering created by the existence of time travel and reality change in Eternity is questioned by the characters as they imagine the impact of constantly molding time to maintain an unexciting equilibrium. Each time the Sociologists’ “life plots” predict some calamity, like nuclear war, they intervene to level things out. And as it turns out, the intention to do good by removing chaos and chance from the equation stagnates humanity’s expansion to greater things, and creates a never ending cyclical machine. History is doomed to repeat itself.

The best science fiction gives itself space to ruminate on the philosophical and moral implications of technology. I loved this book, and found it to be one of the most creative takes on time travel I’ve read, which says a lot given the quantity and variations on the subject in film, television, and writing. It’s all the more impressive that this was written in 1955, and isn’t even one of Asimov’s better-known works. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in science fiction. Its mystery structure keeps things interesting throughout, from a plot perspective, but it doesn’t shy away from classic sci-fi conventions, either.