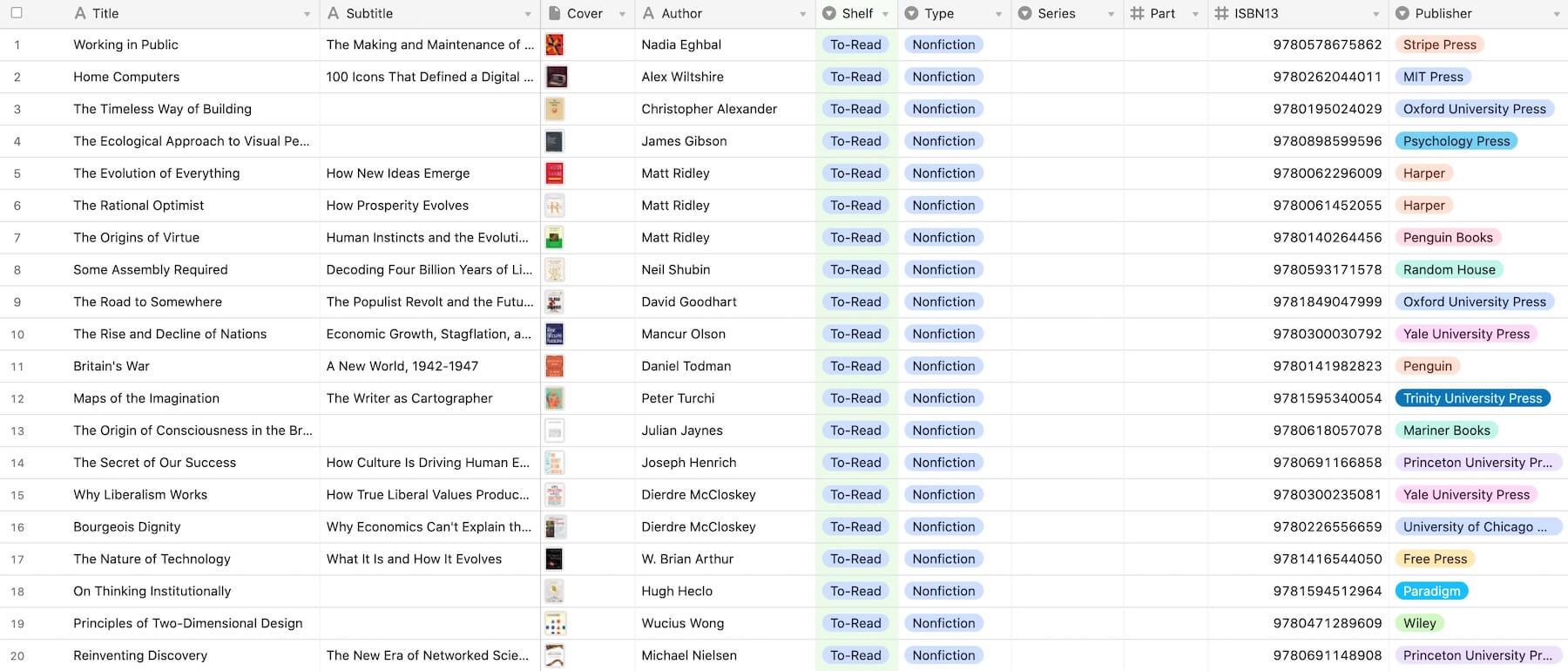

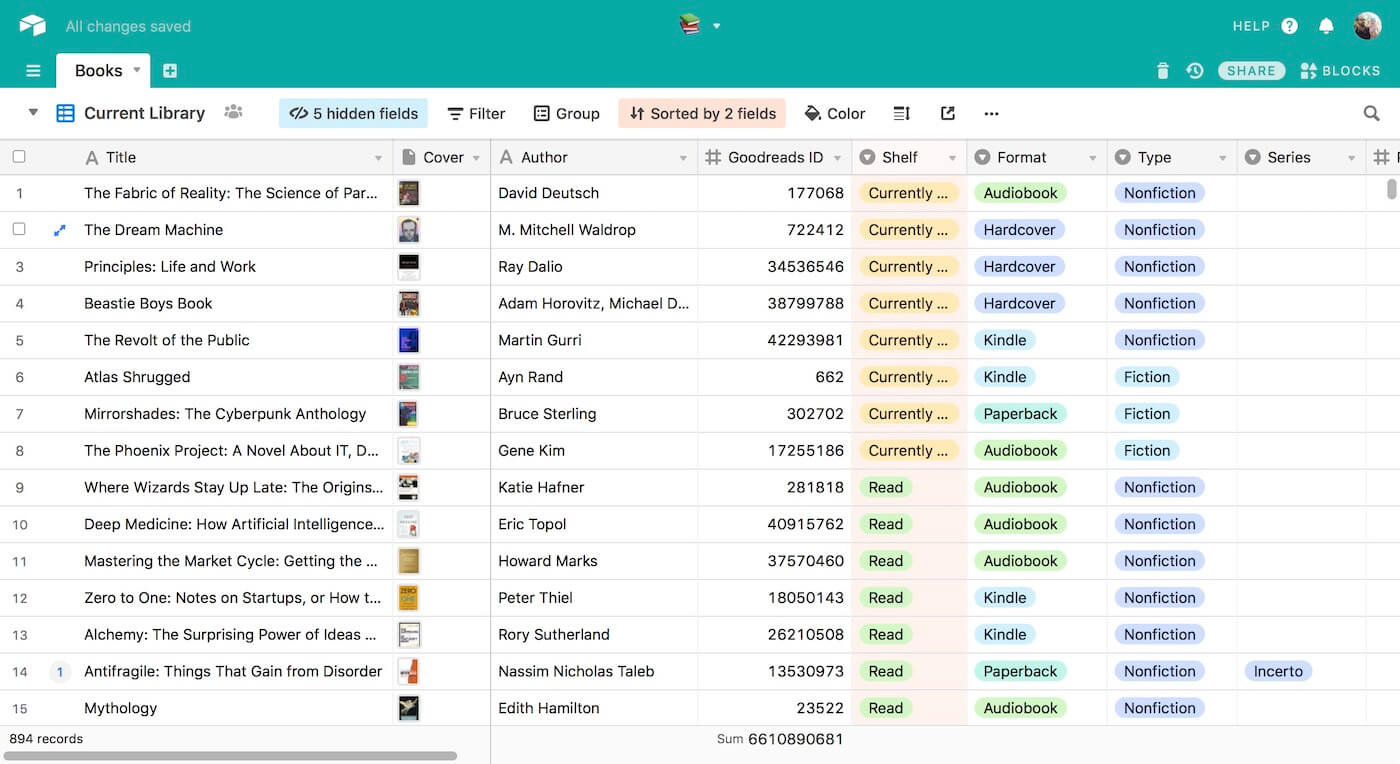

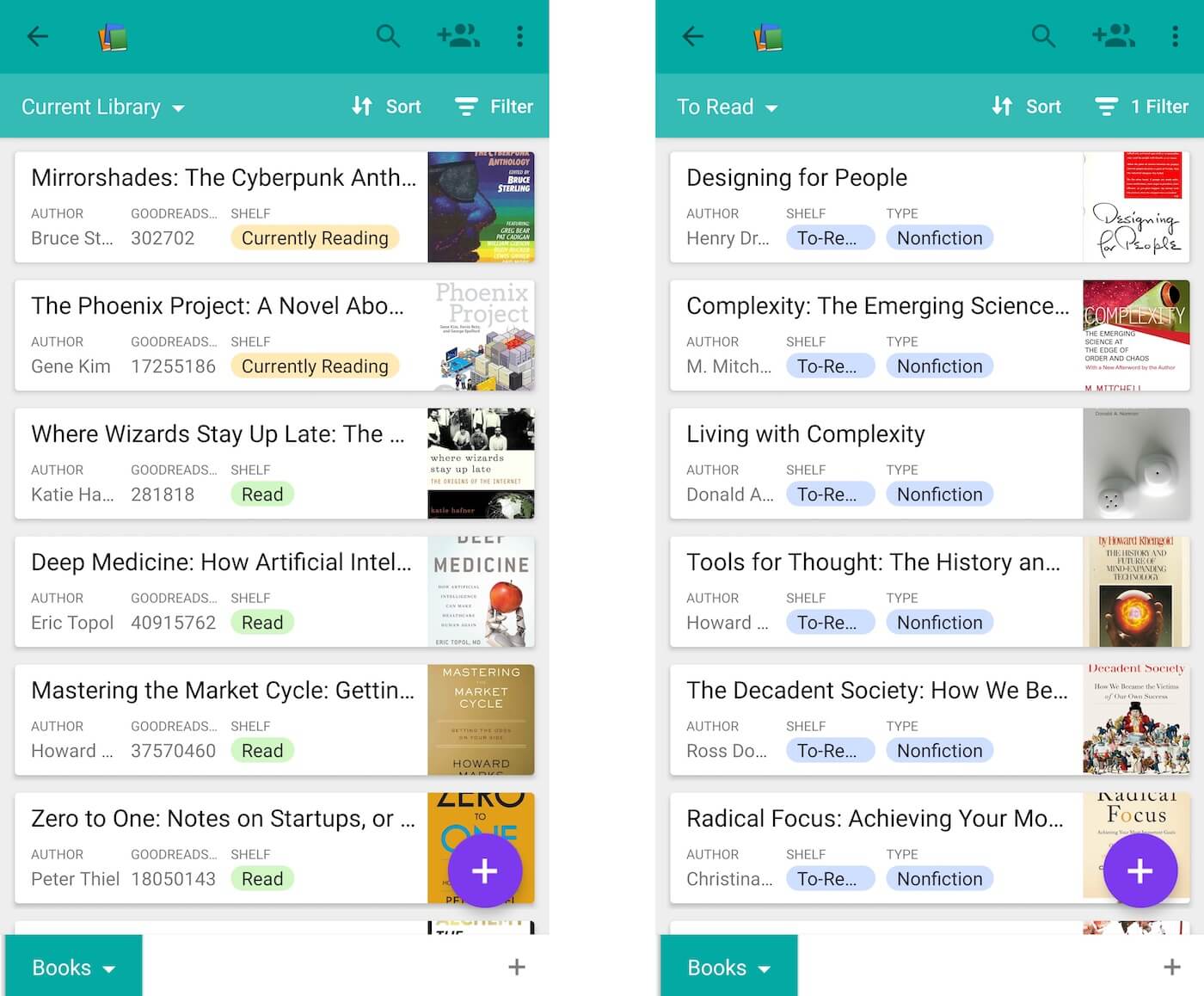

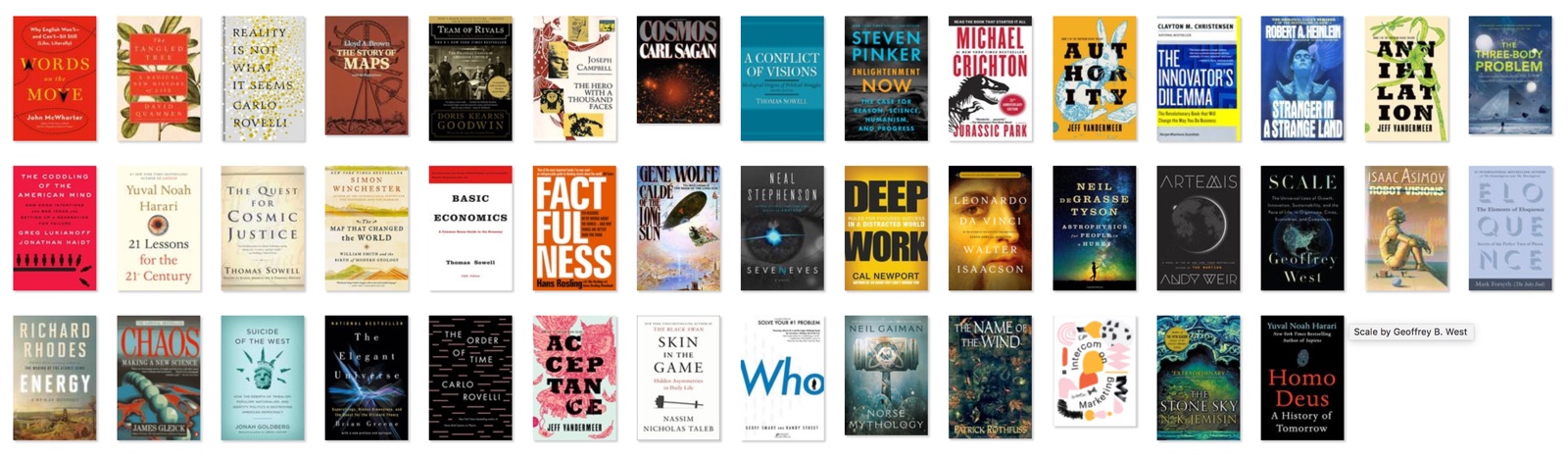

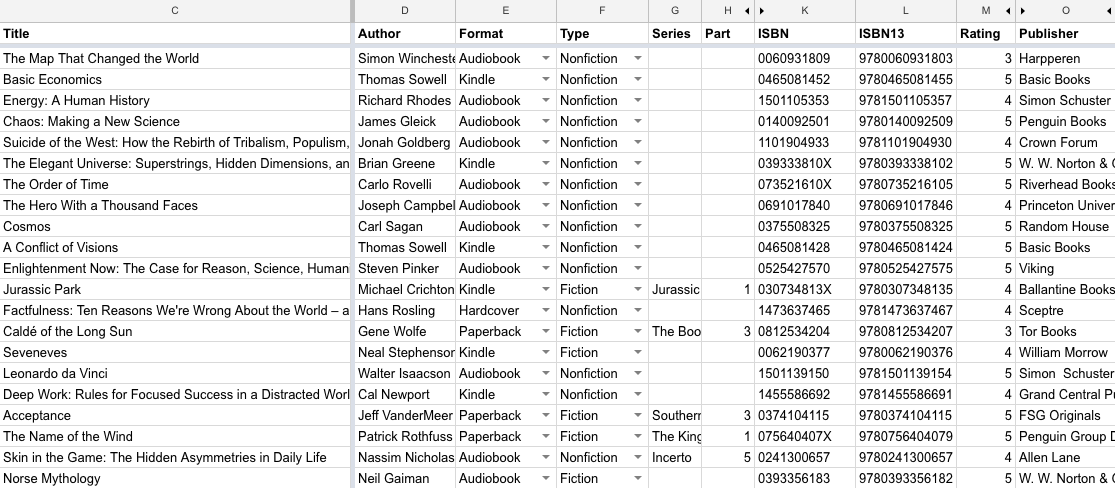

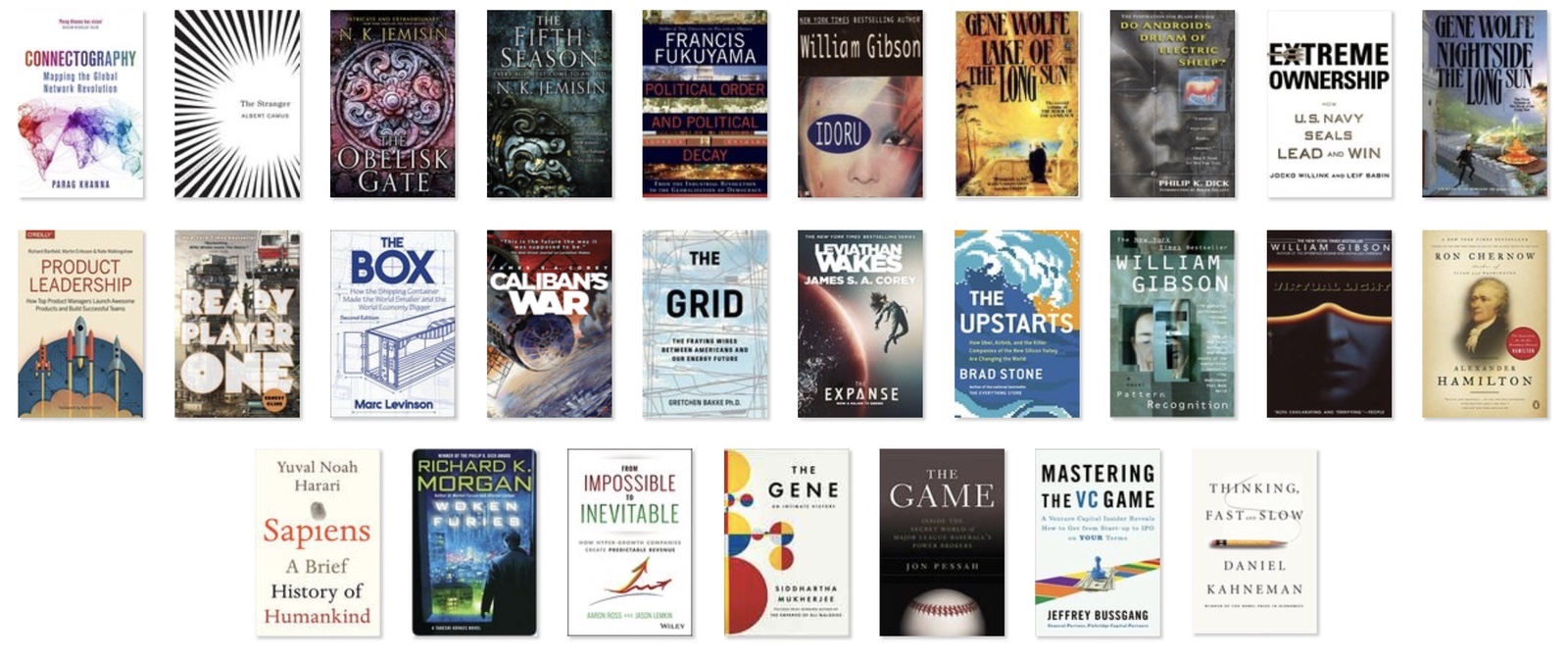

I’ve gotten a lot more selective about books to read in the past few years. My 2020 reading goal was 30 books, giving me space to absorb them and take better notes, and to permit reading longer stuff I could take my time with.

Here’s my list for the year, with stars next to the favorites.

Brave New World

by Aldous Huxley

Published: 1932 • Completed: January 7, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Brave New World

by Aldous Huxley

Published: 1932 • Completed: January 7, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

I had never read Huxley’s classic dystopian science fiction. It was alright, but to me it’s one of those classics better in its influences than the original source material. Wasn’t bad, but didn’t enjoy it as much as I expected I would.

Zero to One

Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

by Peter Thiel

Published: 2014 • Completed: January 11, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Zero to One

Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

by Peter Thiel

Published: 2014 • Completed: January 11, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

On the surface, Zero to One looks like pulpy tech startup how-to book, but it’s better described as an introduction to Thiel’s worldview about business.

Mastering the Market Cycle

Getting the Odds on Your Side

by Howard Marks

Published: 2018 • Completed: January 29, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Mastering the Market Cycle

Getting the Odds on Your Side

by Howard Marks

Published: 2018 • Completed: January 29, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Investor Howard Marks is well known for his memos that lay out his thoughts and opinions on the current state of the market. This book is sort of a collection of his thoughts on the cyclical nature of markets.

Deep Medicine

How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again

by Eric Topol

Published: 2019 • Completed: February 9, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Deep Medicine

How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again

by Eric Topol

Published: 2019 • Completed: February 9, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

A solid read on the state and potential of AI applications in health care. There’s a ton of potential for AI and machine learning in the space, but also a load of hype distracting from its true prospects. Areas like radiology, documentation, note-taking, dictation, and other “mechanical” processes can be moved aside making space for greater unique human connection — things doctors can do that machines can’t. Some fascinating (and often sad) statistics about the methods of modern healthcare.

Where Wizards Stay Up Late

The Origins of the Internet

by Katie Hafner

Published: 1996 • Completed: February 29, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Where Wizards Stay Up Late

The Origins of the Internet

by Katie Hafner

Published: 1996 • Completed: February 29, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

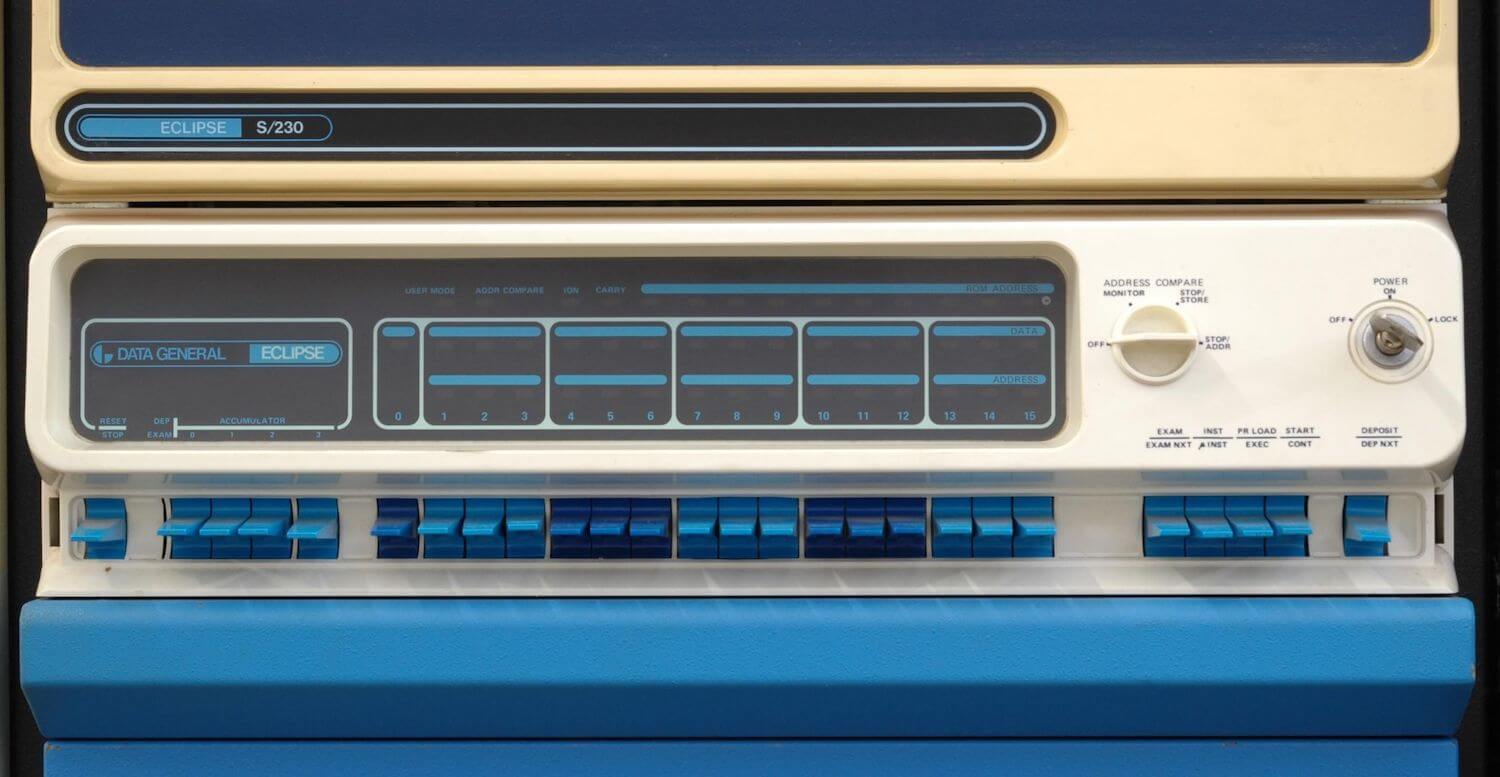

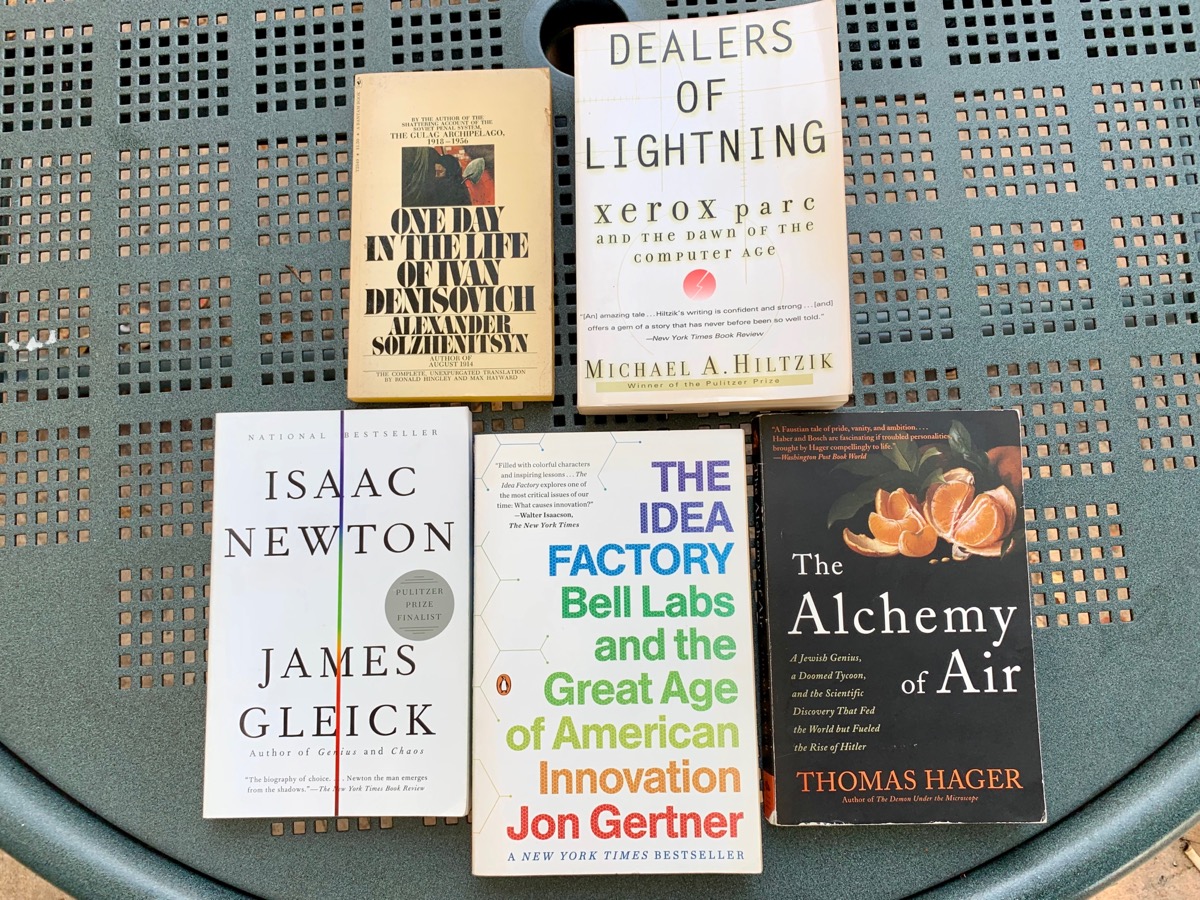

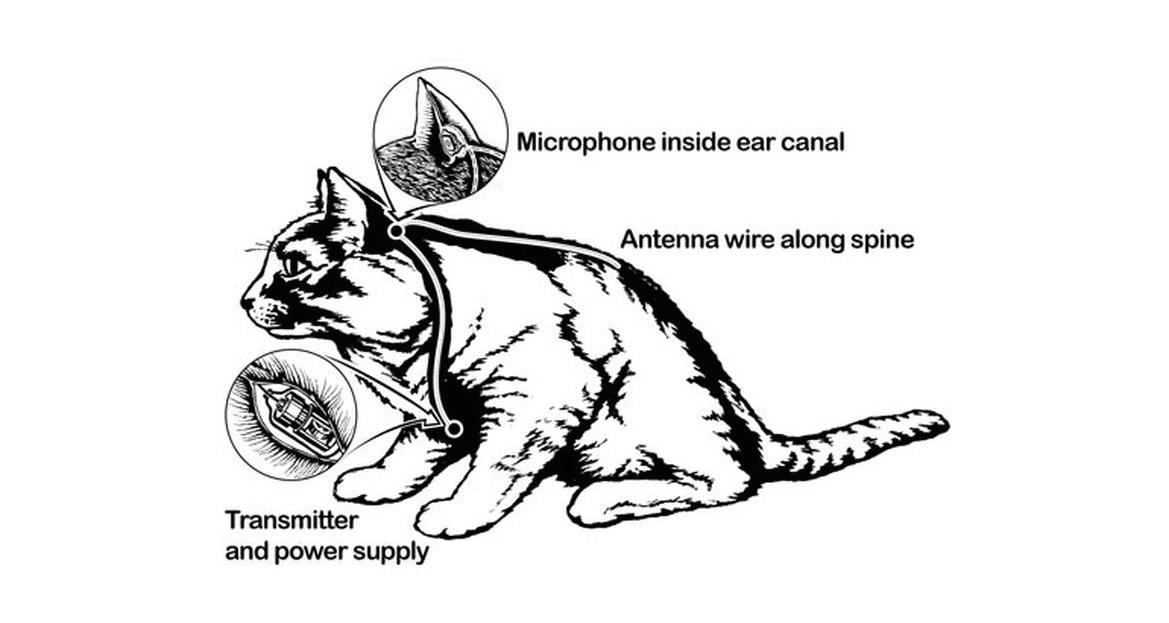

A brief history of the formation of ARPA and the evolution of the internet from the early 1960s to the mid-90s. A quick read and solid primer on the players involved in the early days.

The Phoenix Project

A Novel About IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win

by Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, and George Spafford

Published: 2013 • Completed: March 13, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Phoenix Project

A Novel About IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win

by Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, and George Spafford

Published: 2013 • Completed: March 13, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Three writers with engineering backgrounds write a novelization of a devops team encountering and solving dozens of problems from within their broken technology organization. A revival of Eli Goldratt’s The Goal, covering management science concepts like agile development and the theory of constraints. Much more entertaining than it sounds.

⭐️ The Dream Machine

J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution that Made Computing Personal

by M. Mitchell Waldrop

Published: 2001 • Completed: March 14, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

⭐️ The Dream Machine

J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution that Made Computing Personal

by M. Mitchell Waldrop

Published: 2001 • Completed: March 14, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

I’ve read a lot about the history of computers, but I didn’t realize the deep influence of JCR Licklider until reading this. This book is nominally a biography of “Lick”, but also uses him as a thread to wire together many of the seminal moments in the evolution of computers and the internet, since he was directly involved in so much of it: interactive computing, time-sharing, IPTO/ARPA, funding research at Stanford, UCLA, Berkeley, Engelbart’s work, Project MAC. This was one of my favorites in a long while. Probably generated 20 new books added to my reading list (a strong signal for an interesting work).

I wrote a thread after I finished it with some of the touchpoints of his career.

⭐️ The Revolt of the Public

And the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium

by Martin Gurri

Published: 2014 • Completed: April 9, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

⭐️ The Revolt of the Public

And the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium

by Martin Gurri

Published: 2014 • Completed: April 9, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

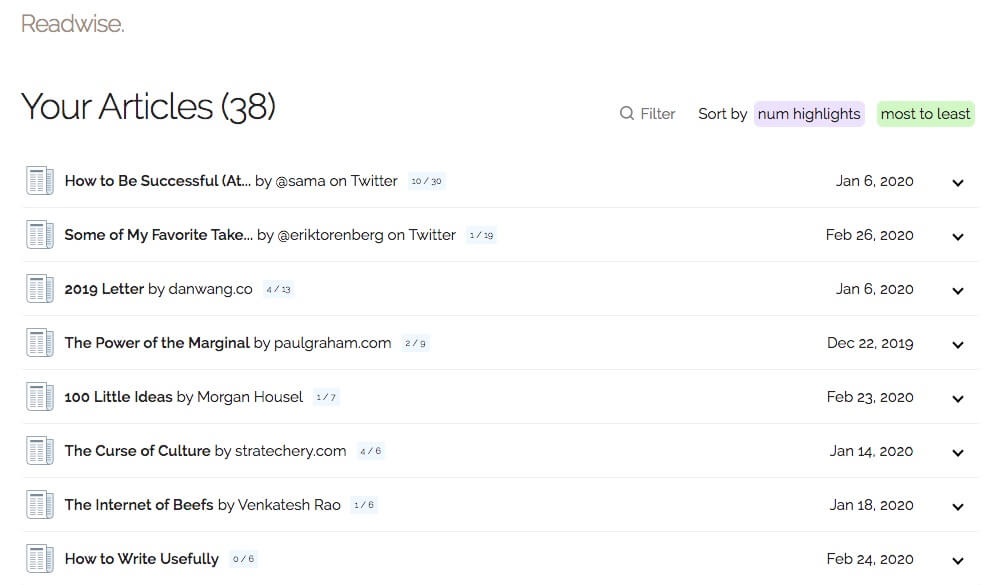

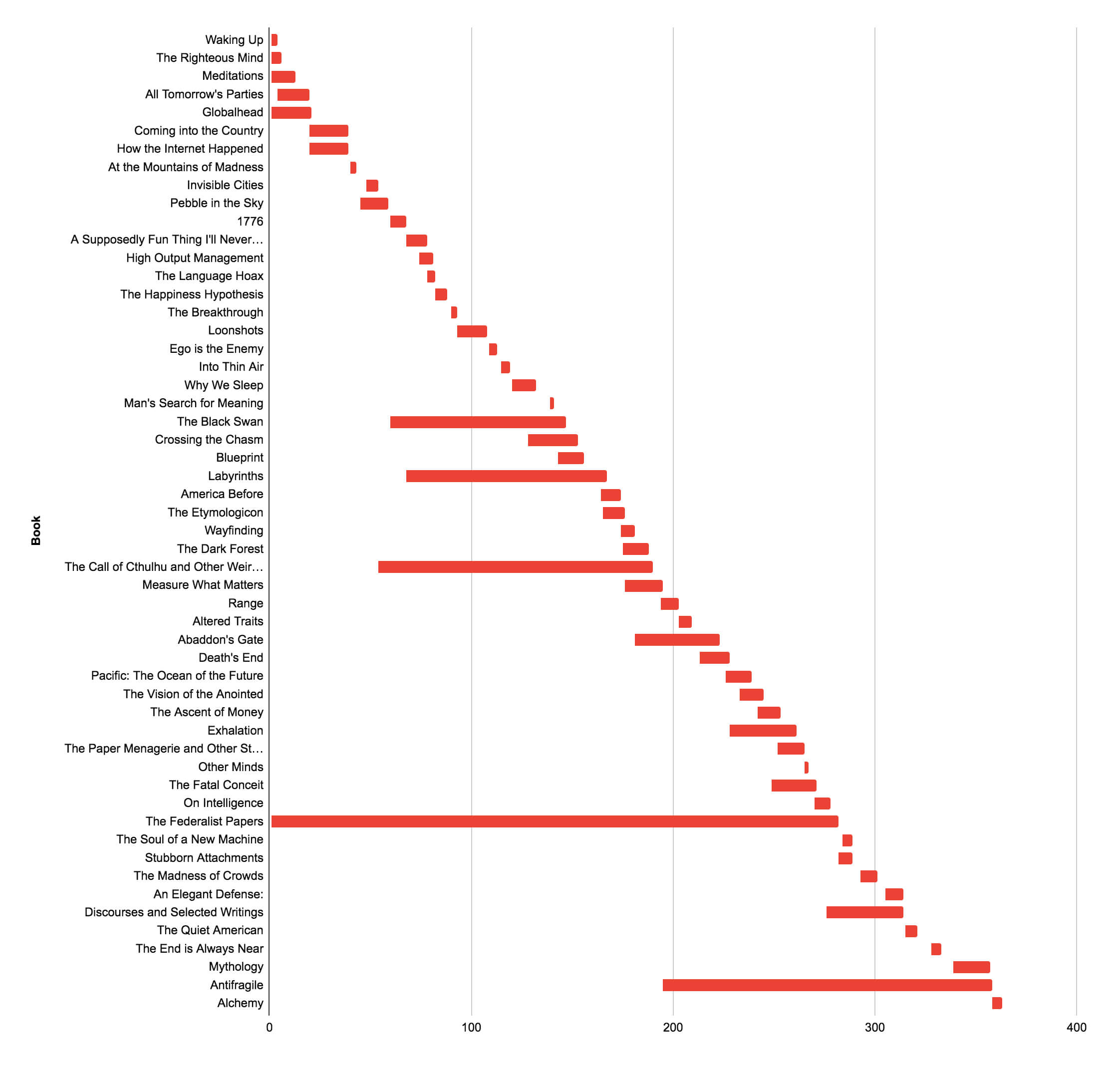

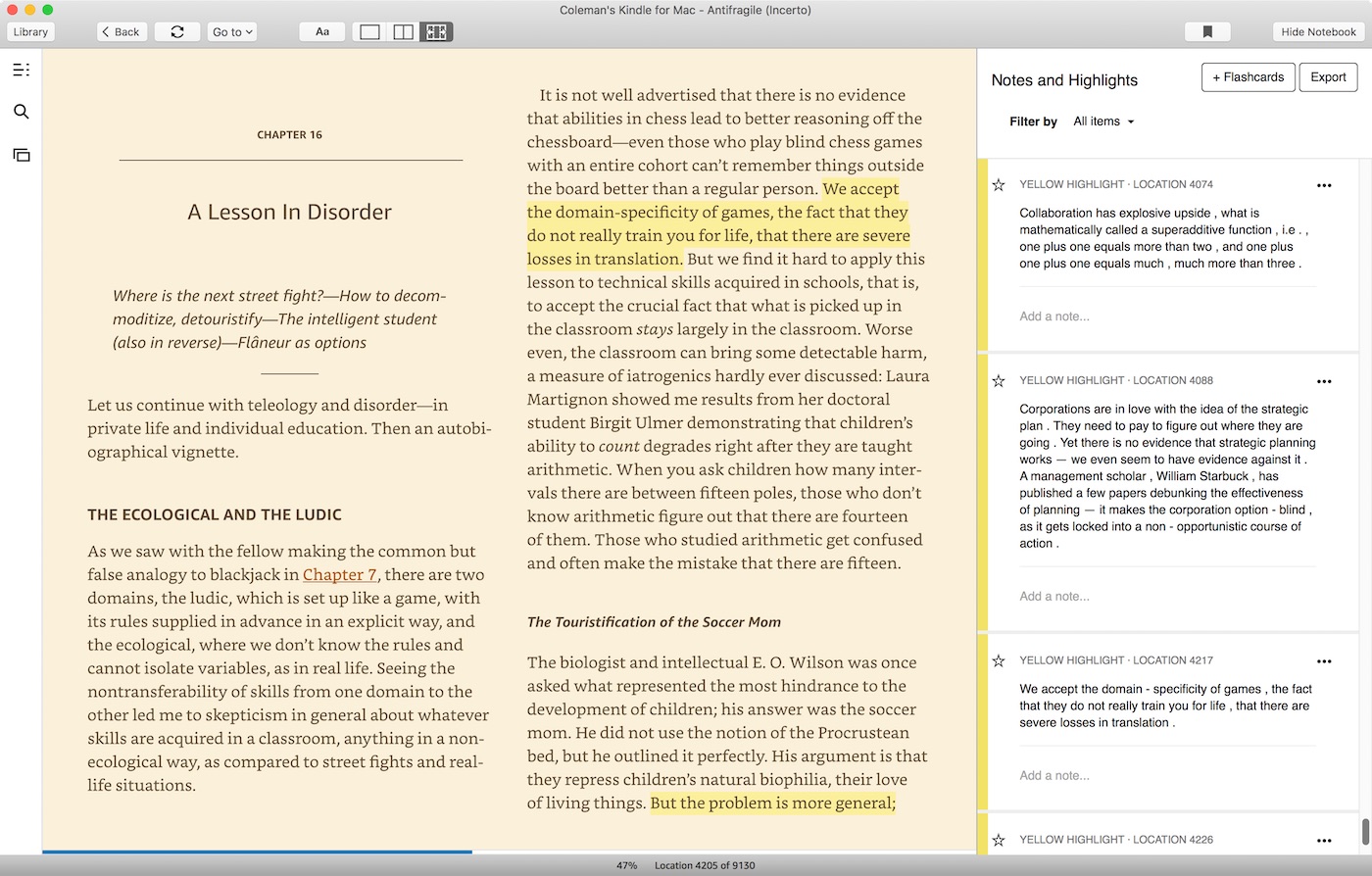

I can measure the “interestingness” of a book by the highlights-to-page-count ratio. Since all of my highlights go to Readwise, it’s funny to look at this number and how accurate that statement is. This book was written in 2014, but reads like Gurri was living in the summer of 2020 when he was writing it. The deep insights into the root causes of dysfunction in institutions, media, and politics show that he was a proverbial Cassandra with the answers to why public outrage, distrust, populism, and social media firestorms have been happening more and more frequently. The book is light on solutions to these problems (Gurri says he “does not make predictions”), but the first step to knowing where to start is to accurately diagnose causes. A phenomenal read. I’m glad to see that Stripe Press reissued it to increase its audience.

Ubik

by Philip K. Dick

Published: 1969 • Completed: April 11, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Ubik

by Philip K. Dick

Published: 1969 • Completed: April 11, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

PKD has a deep bibliography of drug-fueled speculative fiction, and Ubik is one of his most acclaimed. Set in a “future 1992”, it features psychics powers, corporate espionage, reality distortion, time travel — a blitz of crazy sci-fi storytelling in 200 pages.

The Three Languages of Politics

Talking Across the Political Divides

by Arnold Kling

Published: 2013 • Completed: April 20, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Three Languages of Politics

Talking Across the Political Divides

by Arnold Kling

Published: 2013 • Completed: April 20, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

For a few years I’ve gotten interested in the subject of polarization and why we end up with such steep divisions of opinion on literally every single topic. Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind is probably the richest analysis of this, picking apart the moral psychology of why people believe what they believe (and why they think so negatively about their “opposition”).

From his appearances on EconTalk, I started following the work of economist Arnold Kling, who wrote this short book breaking down these definitions from a perspective similar to Haidt’s. He posits that when two people hold differing beliefs and disagree, we’re actually speaking different languages, not even understanding the basis for arguments an opponent is making.

See also this interesting discussion between Kling and Martin Gurri on institutional decay.

⭐️ Darkness at Noon

by Arthur Koestler

Published: 1940 • Completed: April 21, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

⭐️ Darkness at Noon

by Arthur Koestler

Published: 1940 • Completed: April 21, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Picked this up from a mention on The Fifth Column. Koestler fictionalizes Stalin’s Great Purge, telling the story of an old party member called Rubashov, imprisoned and put on show-trial for treason. It’s told from his perspective as he sits in prison recalling the events that led to the party he helped create eating its own.

A Time to Build

From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus, How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream

by Yuval Levin

Published: 2020 • Completed: April 28, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

A Time to Build

From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus, How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream

by Yuval Levin

Published: 2020 • Completed: April 28, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

I’d heard good things about this from interviews with Yuval. There are strong ties from his ideas to those of Gurri in Revolt: the thesis that institutional decay is at the root of many of our modern problems.

How to Take Smart Notes

by Sönke Ahrens

Published: 2017 • Completed: May 16, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

How to Take Smart Notes

by Sönke Ahrens

Published: 2017 • Completed: May 16, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Getting into Roam this year got me seriously rethinking my haphazard note-taking habits. Within the #roamcult community, Ahrens’s book is one of the canon works on the “zettelkasten” method, Niklas Luhmann’s approach to decentralized, network-based thinking. It’s helped me immensely in learning and recall, since I now have a more deliberate approach to knowledge capture from the many books I read.

It’s excellent to see the community springing up around continuous learning, writing, and richer note-taking. Tools like Readwise have also helped to take this to the next level.

Check out this interview with the author, which gives a great overview of his work.

Beastie Boys Book

by Adam Horivitz, Michael Diamond

Published: 2018 • Completed: May 31, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Beastie Boys Book

by Adam Horivitz, Michael Diamond

Published: 2018 • Completed: May 31, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Music bios don’t make frequent appearances in my reading list, but I had to read this one. The Beasties are one of those groups that have maintained high status in my music rotation for 2+ decades. Rarified air, since most sort of tail off or become tired after long enough.

I have a copy of the fantastic hardcover edition, but I actually listened to this one in audio format. Guest narration from folks like Mix Master Mike, Chuck D, MC Serch, LL Cool J, Spike Jonze, and many more folks from their extended universe. Highly recommended.

This one came across through Twitter, a self-published work from writer and programmer Sam Hughes. In the world of Ra, magic is real and studied as a branch of engineering. The protagonist is a practicing mage who ends up caught in a conspiracy. A creative and original work of fantasy/sci-fi.

⭐️ How Innovation Works

And Why it Flourishes in Freedom

by Matt Ridley

Published: 2020 • Completed: June 20, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

⭐️ How Innovation Works

And Why it Flourishes in Freedom

by Matt Ridley

Published: 2020 • Completed: June 20, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

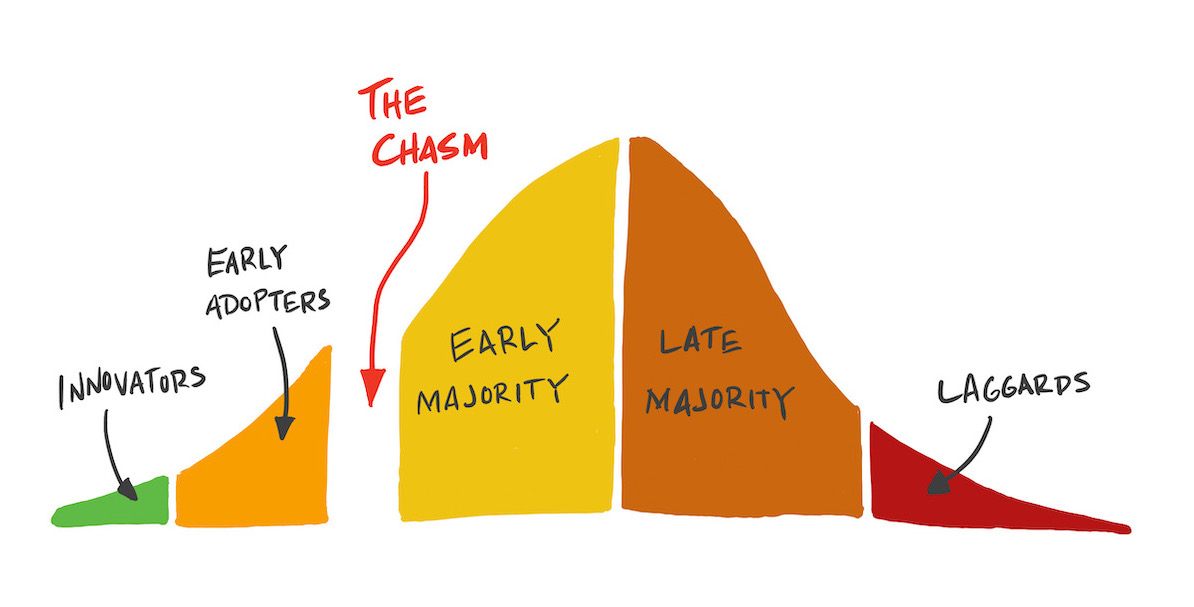

Innovation is a phenomenon frequently taken for granted in today’s world. Since we’ve seen booming improvements in scientific discovery, public health, industrialization, and economics over the past 3 centuries, no one alive today has ever known anything different. So it’s easy to think that innovation springs forth from the ground, a free and bountiful resource we all get to enjoy the fruits of.

But innovation isn’t automatic — it requires giving creative individuals the freedom to experiment, to drive toward continuous improvement through the relentless application of trial and error.

The front half of the book is full of examples sliced from the history of technology and how innovations we all value today originally came to be: Edison’s light bulb, the Wright flyer, nitrogen fixation, vaccinations, the steam engine. Every innovation we know of was not the result of magical, eureka-like discovery, but rather the slow and steady, compounding progression of building on thousands of prior incremental discoveries.

In the back half (which should be required reading in history classes), Ridley succinctly lays out innovation’s essential ingredients — it’s recombinant, team-based, serendipitous, gradual, decentralized — and many other core principles to define innovation’s evolutionary quality.

One of my top reads of 2020, for sure.

I’m hopeful that the rise of the progress studies movement this year will continue to catch on with more people, spreading the understanding of how innovation truly works to a wider audience.

The Lean Startup

How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses

by Eric Ries

Published: 2011 • Completed: July 16, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Lean Startup

How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses

by Eric Ries

Published: 2011 • Completed: July 16, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

This is practically required reading for anyone in the startup world, so I don’t know how I went so many years without reading it. Since it’s been built upon in the culture of tech and become a native part of the lingua franca of the industry, there wasn’t much news to me here. That being said, it’s a solid foundational work in the scene, with many core principles still relevant today and beyond.

The Gervais Principle

Or The Office According to 'The Office'

by Venkatesh Rao

Published: 2013 • Completed: July 30, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Gervais Principle

Or The Office According to 'The Office'

by Venkatesh Rao

Published: 2013 • Completed: July 30, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Venkatesh Rao is one of the most interesting people in the internet writer-verse these days. This one is a collection of long-form essays he wrote, building a theory of business organizations using The Office as a framing device for establishing the nomenclature and examples of his theory, which builds on top of a Hugh MacLeod cartoon from years ago.

It sounds absurd when you start reading it, but continuing through each part you realize how sharply spot-on this analysis of corporate culture is.

The Remains of the Day

by Kazuo Ishiguro

Published: 1989 • Completed: August 5, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Remains of the Day

by Kazuo Ishiguro

Published: 1989 • Completed: August 5, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

This one is highly acclaimed work of historical fiction. The writing is quality and dialogue is incredible, told from the perspective of an English butler at the tail end of his career. I felt it was sort of slow, but had some interesting moments. Would like to read more of Ishiguro’s other work.

Inspired

How To Create Products Customers Love

by Marty Cagan

Published: 2008 • Completed: August 27, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Inspired

How To Create Products Customers Love

by Marty Cagan

Published: 2008 • Completed: August 27, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Marty Cagan’s blog has been a resource for me for years as a product manager. This book collects up Cagan’s organizing principles for how product teams should be assembled and work together. Some solid insights here, but if you’ve read the archives of the SVPG blog, you won’t find any revelations you haven’t already seen.

Mythos

The Greek Myths Retold

by Stephen Fry

Mythos

The Greek Myths Retold

by Stephen Fry

part 1 of Stephen Fry's Great Mythology

Published: 2017 • Completed: October 2, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

For some reason mythologies are fascinating to me. Last year I read Edith Hamilton’s classic Mythology, and before that Gaiman’s revitalization of Norse Mythology and Joseph Campbell’s analysis of myth’s roots in The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Looking at how stories start to form as ways to explain the unexplainable, and how they pass down through culture helps provide a frame for how other ideas coalesce and spread.

Like with Gaiman’s take on the Norse gods, this one is humorist Stephen Fry’s rework of the Greek myths. Compared to other classicists like Hamilton or Bullfinch, Fry’s modern take is far more entertaining and approachable, while still deriving from the same original sources like Hesiod, Ovid, and Homer.

Bonus: Fry’s narration in the audio version is fantastic.

The Psychology of Money

Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

by Morgan Housel

Published: 2020 • Completed: October 3, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Psychology of Money

Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

by Morgan Housel

Published: 2020 • Completed: October 3, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Morgan Housel’s blog is a treasure trove of fascinating ideas. I preordered this one early in the year when it was announced, and devoured it in a couple days when I got it. It’s a great primer on how to think about finances, savings, retirement, from a first-principles perspective, readable by anyone with no prior knowledge of investing or finance required.

The Decadent Society

How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by Ross Douthat

Published: 2020 • Completed: October 16, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Decadent Society

How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by Ross Douthat

Published: 2020 • Completed: October 16, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Back on the topic of stagnation and institutional decay, this one was New York Times columnist Ross Douthat’s entry on that theme. His basic framework defines “decadence” as a society rife with 4 qualities: stagnation, repetition, sterility, and sclerosis.

I’m not sure I share Douthat’s depth of pessimism about the stagnation hypothesis (which has been well written about elsewhere), but there’s some insightful analysis here about possible root causes to some of this stagnation.

Like with Revolt and A Time to Build, it’s hard to prescribe solutions to the problem, but worthwhile figuring out the diagnosis.

Peter Thiel wrote a good essay on the book earlier this year, if you want to read more about it.

Gut Feelings

The Intelligence of the Unconscious

by Gerd Gigerenzer

Published: 2007 • Completed: October 31, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Gut Feelings

The Intelligence of the Unconscious

by Gerd Gigerenzer

Published: 2007 • Completed: October 31, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

I first learned of Gerd Gigerenzer on EconTalk where he discussed the ideas from this book. If you’re familiar with Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink, this covers some of the same concepts, but in a much deeper and interesting way.

The core idea is that when we use our “gut” to make decisions, it’s not random, emotional guesswork driving the rationale; gut is driven by heuristics, rules of thumb, and complex impossible-to-articulate models of reality that we become programmed with through millions of tiny events and experiences. Gigerenzer draws a coherent picture of the theory with many examples of the counterintuitive power of heuristics.

The Splendid and the Vile

A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz

by Erik Larson

Published: 2020 • Completed: November 27, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

The Splendid and the Vile

A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz

by Erik Larson

Published: 2020 • Completed: November 27, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

This one is a great history of Britain through the Blitz of 1940. It mostly follows Churchill and his close circle of family members and advisors as they make their way through from the evacuation at Dunkirk through the German bombing campaign and the eventual entry of the United States into the War. I’ve never read any of Larson’s other work, but he’s a fantastic writer of narrative history. This one reads like a thriller in parts, with the UK perched on a knife’s edge in whether they could withstand the onslaught and successfully fight back.

I wrote a bit about the book in RE 5 a few weeks ago.

⭐️ Seeing Like a State

How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

by James C. Scott

Published: 1998 • Completed: December 2, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

⭐️ Seeing Like a State

How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

by James C. Scott

Published: 1998 • Completed: December 2, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

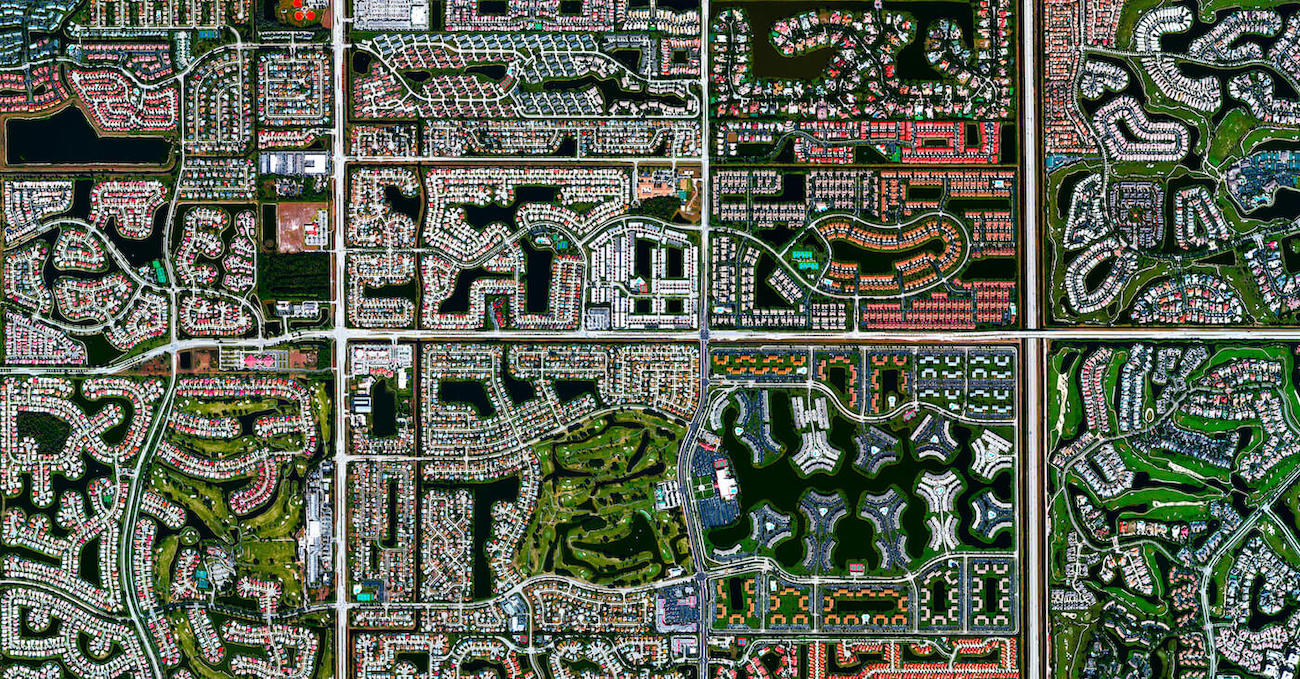

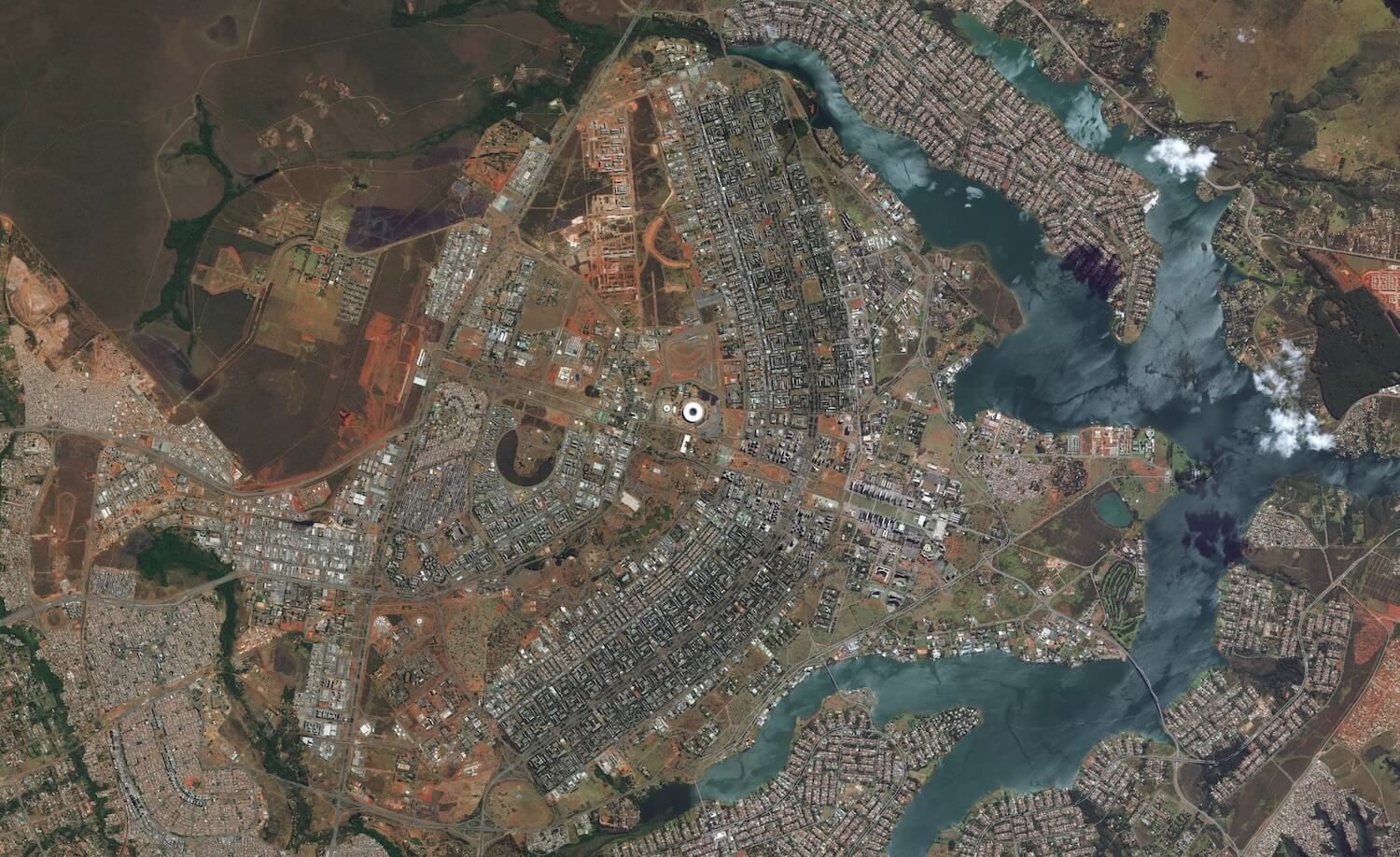

I was tipped off to this one I think originally by a post from a Venkat Rao post, talking about the central theme of the book: legibility.

SLAS centers around a concept Scott calls “authoritarian high modernism”: an approach to organizing society that attempts a planned, centralized scheme for a system — could be a farm, a city, a company, an economic system, or an entire country — with the central goal of making the peripheries more legible to the center. High-modernist designers, planners, or government leaders look at “messy” systems of organization and see a lack of order. Scott’s claim is that this top-down worldview simply ignores or assumes useless what it cannot quantify, monitor, and manage. Complex systems exhibit apparent disorder, but at the lowest levels are often surprisingly rational.

This book is worth revisiting regularly. It was profound to me and connects dots between many other distinct theories and ideas I’ve been interested in.

I went deep on this idea in RE 4. Check that out to read more about legibility.

Competing Against Luck

The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice

by Clayton Christensen

Published: 2016 • Completed: December 6, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Competing Against Luck

The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice

by Clayton Christensen

Published: 2016 • Completed: December 6, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Christensen is most renowned for his work on disruption theory (The Innovator’s Dilemma), but he’s been instrumental in developing “jobs theory”, which I find more practical to apply to the day-to-day process of building. In principle it guides you to think about products or services as things your customers are “hiring” to perform a “job”.

If you’re interested in Jobs Theory stuff, I’ve found Ryan Singer’s work fascinating, following these threads for product-building. His newsletter is great.

Kim

by Rudyard Kipling

Published: 1901 • Completed: December 12, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Kim

by Rudyard Kipling

Published: 1901 • Completed: December 12, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

I’ve had Kipling on my reading list for years and didn’t know where to start on his works. Kim tells the story of an orphan that finds himself drafted into the service of British intelligence in the “Great Game” of geopolitical influence against Russia.

The backdrop is an interesting tour through the different cultures of the Indian subcontinent.

⭐️ Thinking in Systems

A Primer

by Donella Meadows

Published: 2008 • Completed: December 23, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

⭐️ Thinking in Systems

A Primer

by Donella Meadows

Published: 2008 • Completed: December 23, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

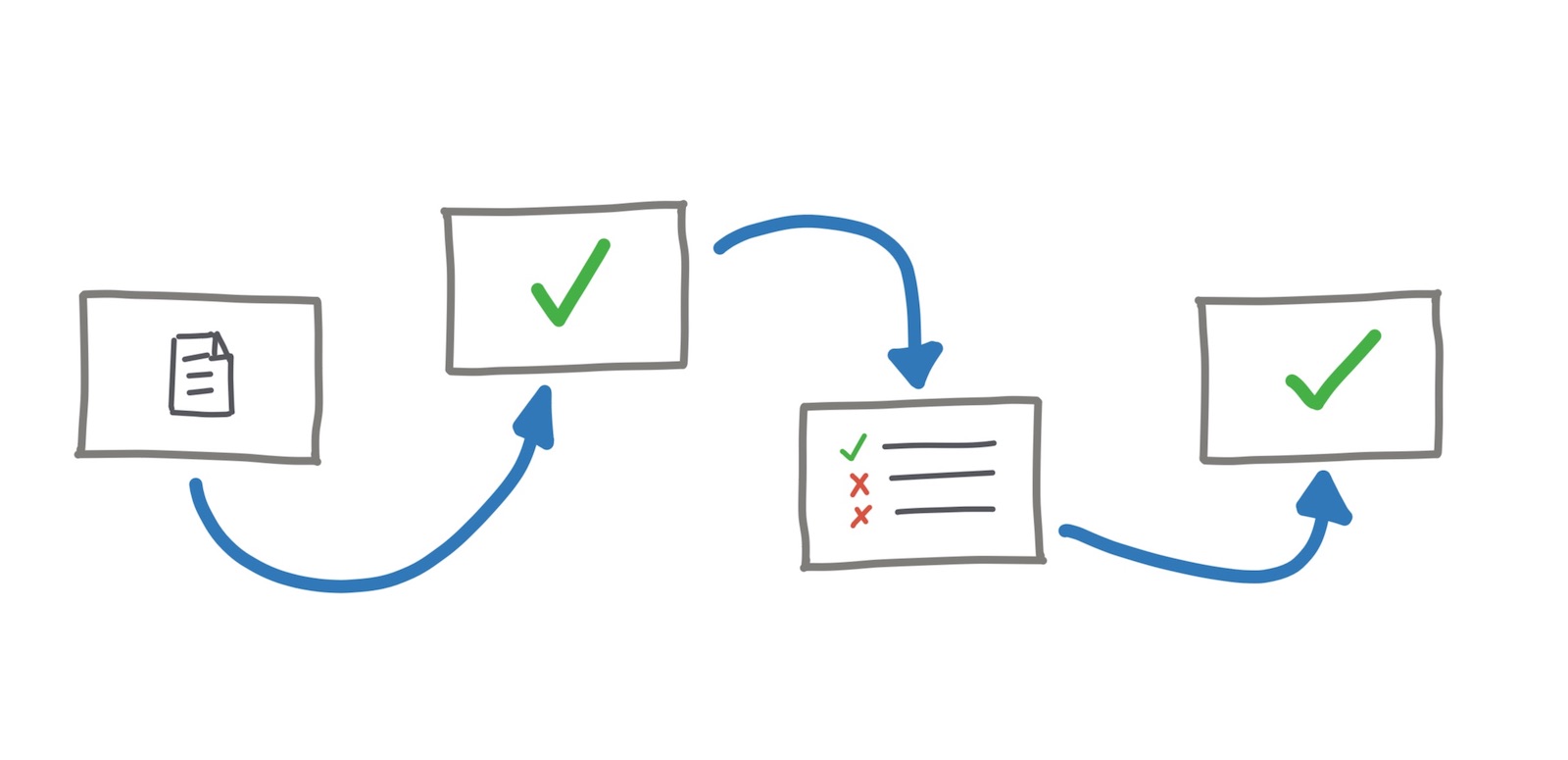

Throughout the year I kept encountering this subject of complex systems. Systems thinking is something I found intriguing, and as happens with many books, a perusal of the first few pages of Dana Meadows’s book quickly turned into consuming the whole thing. As the subtitle says, this book is a fantastic primer on the core principles, and lays out the central elements of stocks and flows with clear diagrams.

I went deeper on systems thinking and feedback loops in RE 6 a couple weeks ago.

Sid Meier's Memoir!

A Life in Computer Games

by Sid Meier

Published: 2020 • Completed: December 31, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

Sid Meier's Memoir!

A Life in Computer Games

by Sid Meier

Published: 2020 • Completed: December 31, 2020 • 📚 View in Library

While I’m not a gamer these days really, except for time with the kids, my youth was spent playing lots of PC games, especially the ones in Sid Meier’s catalog. Civilization II was absolutely formative for me in more ways than entertainment. I’d credit that game with sparking an interest in history, cementing a deeper one in geography, and was the starting point for a love of strategy games of the era.

I’m still working on what my reading goals will look like for this year. I’d like to be more purposeful about studying specific subjects more deeply rather than the semi-haphazard selections I tend to make normally.