The Magic of Hong Kong

January 10, 2020 • #This footage really makes Hong Kong feel like it’s from the future:

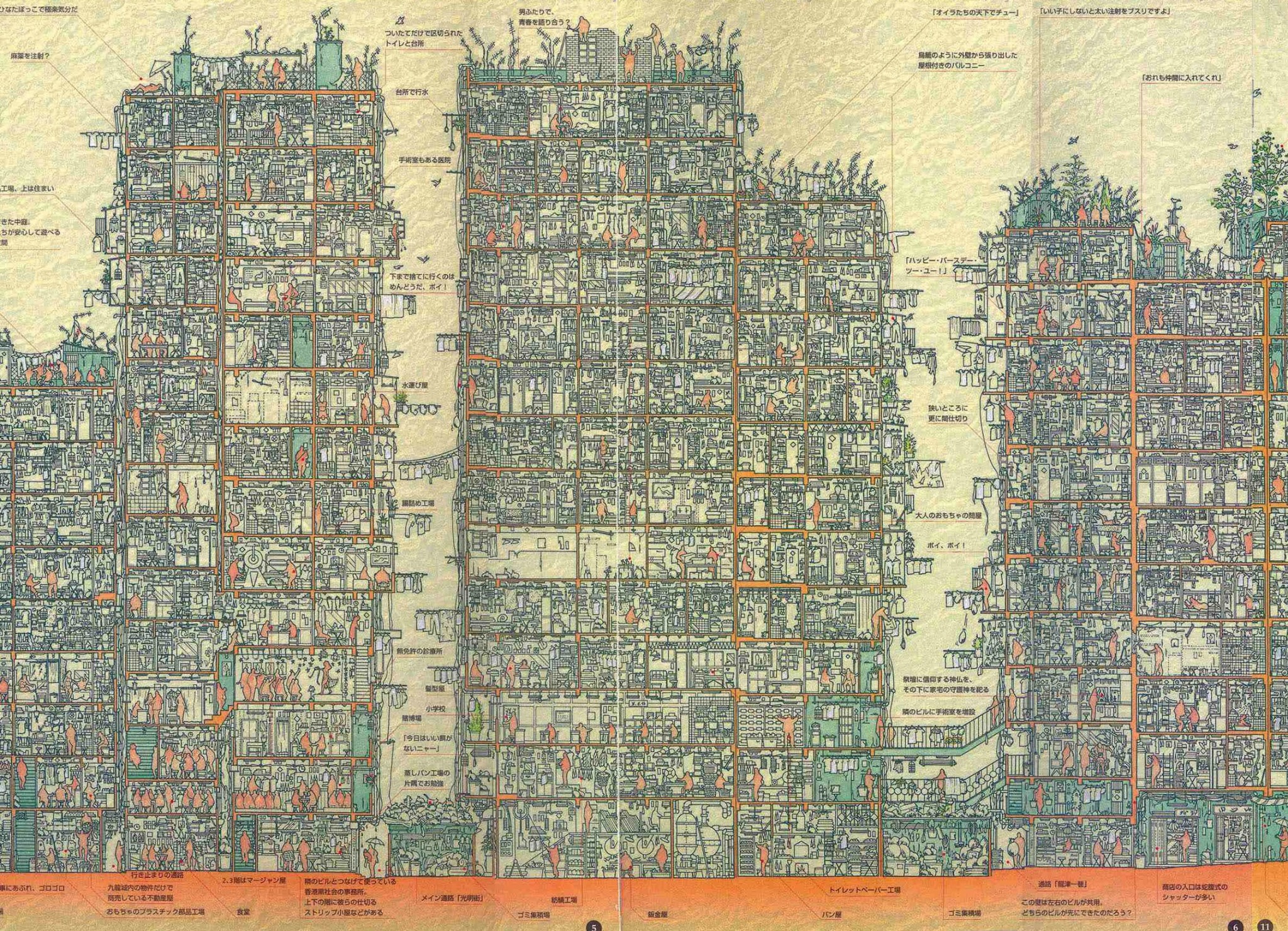

Cross-section of Hong Kong’s Kowloon Walled City.

Bailong Elevator , also known as the Hundred Dragons Elevator , is a glass elevator located in the Wulingyuan area of Zhangjiajie, China. It is considered to be the world’s tallest outdoor elevator, standing at a height of 1,070 feet.

If there’s an superlative example of construction project, you’ll find it in China.

This is a wild story and an incredible piece of investigative journalism from the folks at BuzzFeed. The CCP reportedly operates hundreds of camps across the Xinjiang autonomous region for re-education of Uyghur muslims.

Starting with map tiles they’d noticed were blanked out on China’s Baidu Maps service, they enlisted new data resources, built analysis tools, and combed through map data manually to identify hundreds of these prisons (only several dozen are “officially” known):

We began to sort through the mask tile locations systematically using a custom web tool that we built to support our investigation and help manage the data. We analyzed the whole of Kashgar prefecture, the Uighur heartland, which is in the south of Xinjiang, as well as parts of the neighboring prefecture, Kizilsu, in this way. After looking at 10,000 mask tile locations and identifying a number of facilities bearing the hallmarks of detention centers, prisons, and camps, we had a good idea of the range of designs of these facilities and also the sorts of locations in which they were likely to be found.

They used data tasked on-demand by Planet’s satellite constellation (and granted for free for the project, so big ups to the Planet team there!) to find hundreds more of these:

In total we identified 428 locations in Xinjiang bearing the hallmarks of prisons and detention centers. Many of these locations contain two to three detention facilities — a camp, pretrial administrative detention center, or prison. We intend to analyze these locations further and make our database more granular over the next few months.

Of these locations, we believe 315 are in use as part of the current internment program — 268 new camp or prison complexes, plus 47 pretrial administrative detention centers that have not been expanded over the past four years.

This story gets more shocking every day. It’s hard to believe the resounding silence pretty much worldwide of any government response to this going on. Eric Weinstein recently had a podcast episode about Arthur Koestler’s (author of Darkness at Noon 1944 essay called “The Nightmare That is a Reality,” in which Koestler marvels at the world’s lack of belief and response to the ongoing Holocaust. It was written long before the Allies began to liberate the camps and see for themselves in person what was going on.

Today we have cameras in the sky capable of bypassing lying, twisted regimes of secrecy, but don’t seem to want to believe the truth any more now than we did in 1944.

An interesting post from China analyst Dan Wang, who lives in Beijing, on the current state of the city in the throes of response to the coronavirus response and containment:

I see quarantine enforcement. One day in early February, a uniformed municipal employee set up a tent and a table outside my apartment compound, taking the temperatures of everyone leaving and entering. The next day, he gave me a paper slip, saying that I needed to display it every time I came in. It was a good thing that I received that entry card when I did, because I would have to go through a gauntlet of tests to be issued one today. These guards have been the chief enforcers of the quarantines, making sure that those who return from overseas or other provinces have to stay indoors. Given that everyone lives in big apartment compounds, it’s more or less possible to make sure that only approved people are allowed in or out of every residence. From where these enforcers emerged is a mystery. The source of their legal authority to regulate my entry is unclear to me; sometimes the entrance is staffed by volunteers, whom I assume are retired Party members.

This footage really makes Hong Kong feel like it’s from the future:

I don’t follow international markets closely enough to keep up with this, but interesting to see this take on Hong Kong’s relative stagnation in recent years, especially as compared to other nearby mainland China cities like Shenzhen and Guangzhou:

Despite the transformation the global economy has undergone, Hong Kong’s business landscape remains largely unchanged – the preserve of a small body of property developers and conglomerates, most of them tycoon-owned, who rose to prominence long before the handover. Indeed, one of the most striking things of the city’s history for nearly three decades has been its failure to produce a single major new business.

Responsibility can be attributed to the Basic Law, the mini-constitution that has guided Hong Kong’s governance since its return to China. Passed by China’s parliament seven years before the handover, it came with a built-in bias aimed at preserving Hong Kong’s late-colonial features: a low-tax, capitalist economy, externally very open but domestically protectionist, and overseen by an executive-led government with little formal accountability.

Interesting thoughts in Dan Wang’s annual letter. On China, trade, and tech.

These are not trivial achievements. But neither are they earth-shattering successes. Consider first the internet companies. I find it bizarre that the world has decided that consumer internet is the highest form of technology. It’s not obvious to me that apps like WeChat, Facebook, or Snap are doing the most important work pushing forward our technologically-accelerating civilization. To me, it’s entirely plausible that Facebook and Tencent might be net-negative for technological developments. The apps they develop offer fun, productivity-dragging distractions; and the companies pull smart kids from R&D-intensive fields like materials science or semiconductor manufacturing, into ad optimization and game development.

The internet companies in San Francisco and Beijing are highly skilled at business model innovation and leveraging network effects, not necessarily R&D and the creation of new IP. (That’s why, I think, that the companies in Beijing work so hard. Since no one has any real, defensible IP, the only path to success is to brutally outwork the competition.) I wish we would drop the notion that China is leading in technology because it has a vibrant consumer internet. A large population of people who play games, buy household goods online, and order food delivery does not make a country a technological or scientific leader.

The whole thing is an excellent read.

In the category of good news, this study from NASA using MODIS satellite data shows trends of re-greening happening in countries like India and China. Surprising given the media attention on overexploitation of land:

The world is literally a greener place than it was 20 years ago, and data from NASA satellites has revealed a counterintuitive source for much of this new foliage: China and India. A new study shows that the two emerging countries with the world’s biggest populations are leading the increase in greening on land. The effect stems mainly from ambitious tree planting programs in China and intensive agriculture in both countries.

Pleasantly shocking numbers on the quantity this amounts to:

Taken all together, the greening of the planet over the last two decades represents an increase in leaf area on plants and trees equivalent to the area covered by all the Amazon rainforests. There are now more than two million square miles of extra green leaf area per year, compared to the early 2000s – a 5% increase.

You may have thought the entire 14th century was pretty bad, or maybe 1918 with its flu pandemic and millions of war casualties, but how about the 6th:

A mysterious fog plunged Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia into darkness, day and night—for 18 months. “For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during the whole year,” wrote Byzantine historian Procopius. Temperatures in the summer of 536 fell 1.5°C to 2.5°C, initiating the coldest decade in the past 2300 years. Snow fell that summer in China; crops failed; people starved. The Irish chronicles record “a failure of bread from the years 536–539.” Then, in 541, bubonic plague struck the Roman port of Pelusium, in Egypt. What came to be called the Plague of Justinian spread rapidly, wiping out one-third to one-half of the population of the eastern Roman Empire and hastening its collapse, McCormick says.

That sort of worldwide famine caused by devastating volcanic eruptions would’ve been impossible to deal with. And the Plague of Justinian was no small thing either, thought to have killed up to 25% of the global population.

Life is good these days.

The Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy (translated by Ken Liu and featured here) is one of the best sci-fi works there is, regardless of origin or era. I also read and enjoyed Liu’s Paper Menagerie collection of short stories. I didn’t realize how involved he was personally in bringing so much new material here, and introducing so many Chinese authors to wider audiences:

He has found sci-fi stories in unusual corners of the internet, including a forum for alumni of Tsinghua University. Chinese friends send him screenshots of stories published on apps that are hard to access outside of China. As an emissary for some of China’s most provocative and boundary-breaking writers, Liu has become much more than a scout and a translator. He’s now a fixer, an editor and a curator — a savvy interpreter who has done more than anyone to bridge the imagination gap between the world’s current, fading superpower and its ascendant one.

His job as a translator, given the sensitivities of the material and the players involved, is a complex one:

“It’s a very tricky dance of trying to get the message that they’re trying to convey out, without painting the writers as dissidents,” Liu told me over coffee one day, as we sat in the kitchen of his home in Massachusetts. “A lot of Chinese writers are very skilled at writing something ambiguously, such that there are multiple meanings in the text. I have to ask them, how explicit do you want me to be in terms of making a certain point here, because in the original it’s very constrained, so how much do you want me to tease out the implications you’re making? And sometimes we have a discussion about exactly what that means and how they want it to be done.”

We’ve not scratched the surface much on Slack’s Shared Channels feature, but where we have it definitely makes staying plugged in with important tangential networks (like customers and partners) dead simple and much more engaging.

This network analysis uses some interesting visualizations to show the topology of the network, with its subnetworks creating a connection graph of communication pipes.

Also on an hourly basis, these mini-networks from the outer ring get sucked into the internal mega-network, as connections are formed between organizations on the inside and the outside. The overall result is a roiling sea of proto-networks surrounding an ever-expanding network of super-connected teams.

An interesting technical breakdown on how Figma built their multiplayer tech (the collaboration capability where you can see other users’ mouse cursors and highlights in the same document, in real time).

A fascinating paper. This research suggests the possibility that group-conforming versus individualistic cultures may have roots in diet and agricultural practices. From the abstract:

Cross-cultural psychologists have mostly contrasted East Asia with the West. However, this study shows that there are major psychological differences within China. We propose that a history of farming rice makes cultures more interdependent, whereas farming wheat makes cultures more independent, and these agricultural legacies continue to affect people in the modern world. We tested 1162 Han Chinese participants in six sites and found that rice-growing southern China is more interdependent and holistic-thinking than the wheat-growing north. To control for confounds like climate, we tested people from neighboring counties along the rice-wheat border and found differences that were just as large. We also find that modernization and pathogen prevalence theories do not fit the data.

An interesting thread to follow, but worthy of skepticism given the challenge of aggregating enough concrete data to prove anything definitively. There’s some intuitively sensible argument here as to the fundamental differences with subsistence practices in wheat versus rice farming techniques:

The two biggest differences between farming rice and wheat are irrigation and labor. Because rice paddies need standing water, people in rice regions build elaborate irrigation systems that require farmers to cooperate. In irrigation networks, one family’s water use can affect their neighbors, so rice farmers have to coordinate their water use. Irrigation networks also require many hours each year to build, dredge, and drain—a burden that often falls on villages, not isolated individuals.

I’ve talked before about my astonishment with the immune system’s complexity and power. This piece talks about tuft cells and how they use their chemosensory powers to identify parasites and alert the immune system to respond:

Howitt’s findings were significant because they pointed to a possible role for tuft cells in the body’s defenses — one that would fill a conspicuous hole in immunologists’ understanding. Scientists understood quite a bit about how the immune system detects bacteria and viruses in tissues. But they knew far less about how the body recognizes invasive worms, parasitic protozoa and allergens, all of which trigger so-called type 2 immune responses. Howitt and Garett’s work suggested that tuft cells might act as sentinels, using their abundant chemosensory receptors to sniff out the presence of these intruders. If something seems wrong, the tuft cells could send signals to the immune system and other tissues to help coordinate a response.

Given the massive depth of knowledge about biological processes, anatomy, and medical research, it’s incredible how much we still don’t know about how organisms work. Evolution, selection, and time can create some truly complex systems.

A project from DeepMind designed to fill in missing text from ancient inscriptions:

Pythia takes a sequence of damaged text as input, and is trained to predict character sequences comprising hypothesised restorations of ancient Greek inscriptions (texts written in the Greek alphabet dating between the seventh century BCE and the fifth century CE). The architecture works at both the character- and word-level, thereby effectively handling long-term context information, and dealing efficiently with incomplete word representations (Figure 2). This makes it applicable to all disciplines dealing with ancient texts (philology, papyrology, codicology) and applies to any language (ancient or modern).

They’ve only launched 60 so far, but it looks like SpaceX has big plans for their future broadband satellite constellation.

I haven’t read much Chinese history, but its origins and the Mao years were one of the greatest tragedies. And it’s frightening how much of that attitude is still there under the facade:

China today, for any visitor who remembers the country from 20 or 30 years ago, seems hardly recognizable. One of the government’s greatest accomplishments is to have distanced itself so successfully from the Mao era that it seems almost erased. Instead of collective poverty and marching Red Guards, there are skyscrapers, new airports, highways, railway stations, and bullet trains. Yet scratch the glimmering surface and the iron underpinnings of the one-party state become apparent. They have barely changed since 1949, despite all the talk about “reform and opening up.” The legacy of liberation is a country still in chains.

In the era of every company trying to play in machine learning and AI technology, I thought this was a refreshing perspective on data as a defensible element of a competitive moat. There’s some good stuff here in clarifying the distinction between network effects and scale effects:

But for enterprise startups — which is where we focus — we now wonder if there’s practical evidence of data network effects at all. Moreover, we suspect that even the more straightforward data scale effect has limited value as a defensive strategy for many companies. This isn’t just an academic question: It has important implications for where founders invest their time and resources. If you’re a startup that assumes the data you’re collecting equals a durable moat, then you might underinvest in the other areas that actually do increase the defensibility of your business long term (verticalization, go-to-market dominance, post-sales account control, the winning brand, etc).

Companies should perhaps be less enamored of the “shiny object” of derivative data and AI, and instead invest in execution in areas challenging for all businesses.

An insightful piece this week from Ben Thompson on the current state of the trade standoff between the US and China, and the blocking of Chinese behemoths like Huawei and ZTE. The restrictions on Huawei will mean some major shifts in trade dynamics for advanced components, chip designs, and importantly, software like Android:

The reality is that China is still relatively far behind when it comes to the manufacture of most advanced components, and very far behind when it comes to both advanced processing chips and also the equipment that goes into designing and fabricating them. Yes, Huawei has its own system-on-a-chip, but it is a relatively bog-standard ARM design that even then relies heavily on U.S. software. China may very well be committed to becoming technologically independent, but that is an effort that will take years.

The piece references this article from Bloomberg, an excellent read on the state of affairs here.

I continue to be interested in where the world is headed with remote work. Here InVision’s Mark Frein looks back at what traits make for effective distributed companies, starting with history of past experiences of remote collaboration from music production, to gaming, to startups. As he points out, you can have healthy or harmful cultures in both local and distributed companies:

Distributed workplaces will not be an “answer” to workplace woes. There will be dreary and sad distributed workplaces and engaged and alive ones, all due to the cultural experience of those virtual communities. The key to unlocking great distributed work is, quite simply, the key to unlocking great human relationships — struggling together in positive ways, learning together, playing together, experiencing together, creating together, being emotional together, and solving problems together. We’ve actually been experimenting with all these forms of life remote for at least 20 years at massive scales.

Shot from the Oriental Pearl Tower, the picture shows enormous levels of detail composited from 8,700 source photos. Imagine this capability available commercially from microsatellite platforms. Seems like an inevitability.

I, like many, have admired Basecamp for a long time in how they run things, particularly Ryan Singer’s work on product design. This talk largely talks about how they build product and work as an organized team.

This is an open source framework for building documentation sites, built with React. We’re currently looking at this for revamping some of our docs and it looks great. We’ll be able to build the docs locally and deploy with GitHub Pages like always, but it’ll replace the cumbersome stuff we’ve currently got in Jekyll (which is also great, but requires a lot of legwork for documentation sites).

Part of Vox’s Borders video series. Hong Kong is such a fascinating and unique place, as is today’s China, though for massively different reasons. How China treats HK will be one of the indicators of the wider Chinese plan for free market economics and political openness.

China installed more than 10,000,000 surveillance cameras in 2010. Talk about a stream of “big data”:

In May, Shanghai announced that a team of 4,000 monitor its surveillance feeds to ensure round-the-clock coverage. The south-western municipality of Chongqing has announced plans to add 200,000 cameras by 2014 because “310,000 digital eyes are not enough”.

Urumqi, which saw vicious ethnic violence in 2009, installed 17,000 high-definition, riot-proof cameras last year to ensure “seamless” surveillance. Fast-developing Inner Mongolia plans to have 400,000 units by 2012. In the city of Changsha, the Furong district alone reportedly has 40,000 – one for every 10 inhabitants.