This is an essay I wrote that was published in the OpenForum Academy’s “Thoughts on Open Innovation” book in early summer 2013. Shane Coughlan invited me to contribute on open innovation in geographic data, so I wrote this piece on OpenStreetMap and its implications for community-building, citizen engagement, and transparency in mapping. Enjoy.

With the growth of the open data movement, governments and data publishers are looking to enhance citizen participation. OpenStreetMap, the wiki of world maps, is an exemplary model for how to build community and engagement around map data. Lessons can be learned from the OSM model, but there are many places where OpenStreetMap might be the place for geodata to take on a life of its own.

With the growth of the open data movement, governments and data publishers are looking to enhance citizen participation. OpenStreetMap, the wiki of world maps, is an exemplary model for how to build community and engagement around map data. Lessons can be learned from the OSM model, but there are many places where OpenStreetMap might be the place for geodata to take on a life of its own.

The open data movement has grown in leaps and bounds over the last decade. With the expansion of the Internet, and spurred on by things like Wikipedia, SourceForge, and Creative Commons licenses, there’s an ever-growing expectation that information be free. Some governments are rushing to meet this demand, and have become accustomed to making data open to citizens: policy documents, tax records, parcel databases, and the like. Granted, the prevalence of open information policies is far from universal, but the rate of growth of government open data is only increasing. In the world of commercial business, the encyclopedia industry has been obliterated by the success of Wikipedia, thanks to the world’s subject matter experts having an open knowledge platform. And GitHub’s meteoric growth over the last couple of years is challenging how software companies view open source, convincing many to open source their code to leverage the power of software communities. Openness and collaborative technologies are on an unceasing forward march.

In the context of geographic data, producers struggle to understand the benefits of openness, and how to achieve the same successes enjoyed by other open source initiatives within the geospatial realm. When assessing the risk-reward of making data open, it’s easy to identify reasons to keep it private (How is security handled? What about updates? Liability issues?), and difficult to quantify potential gains. As with open sourcing software, it takes a mental shift on the part of the owner to redefine the notion of “ownership” of the data. In the open source software world, proprietors of a project can often be thought of more as “stewards” than owners. They aren’t looking to secure the exclusive rights to the access and usage of a piece of code for themselves, but merely to guide the direction of its development in a way that suits project objectives. Map data published through online portals is great, and is the first step to openness. But this still leaves an air gap between the data provider and the community. Closing this engagement loop is key to bringing open geodata to the same level of genuine growth and engagement that’s been achieved by Wikipedia.

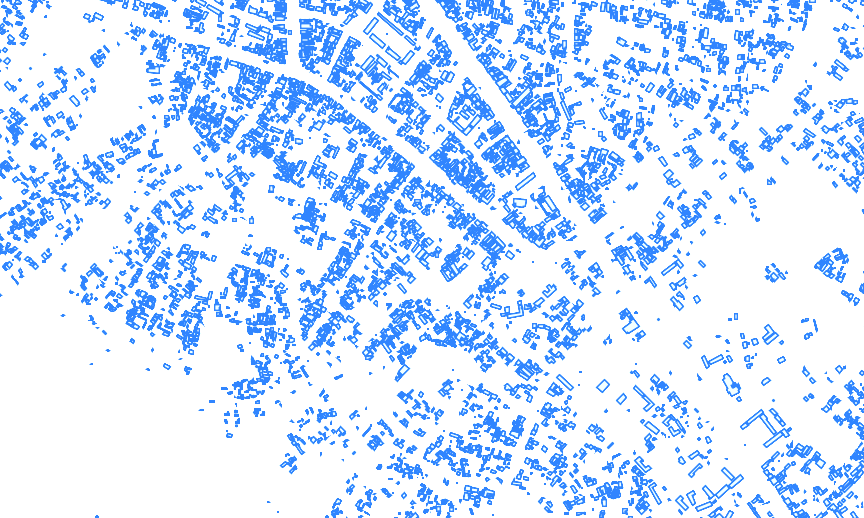

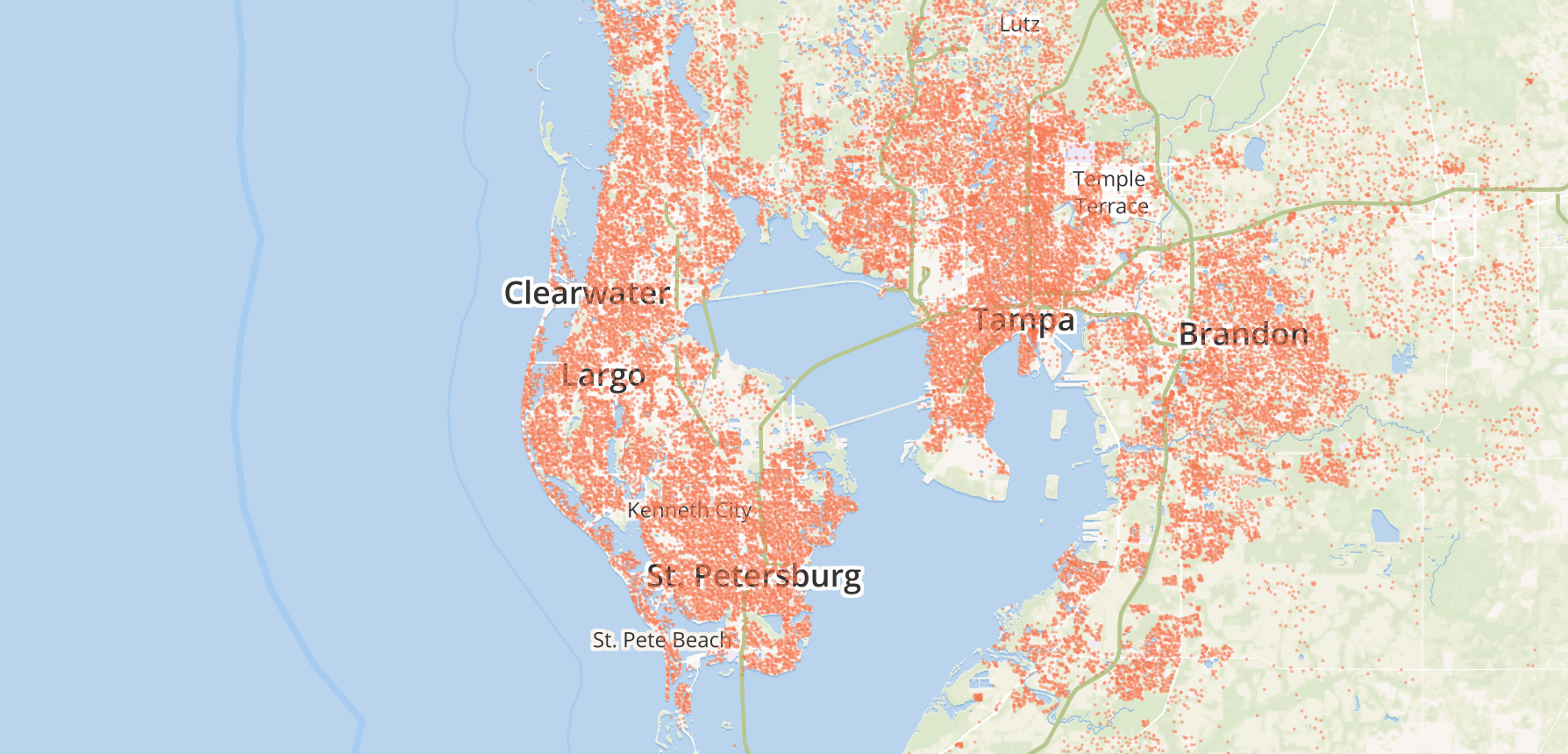

An innovative new approach to open geographic data is taking place today with the OpenStreetMap project. OpenStreetMap is an effort to build a free and open map of the entire world, created from user contributions – to do for maps what Wikipedia has done for the encyclopedia. Anyone can login and edit the map – everything from business locations and street names to bus networks, address data, and routing information. It began with the simple notion that if I map my street and you map your street, then we share data, both of us have a better map. Since its founding in 2004 by Steve Coast, the project has reached over 1 million registered users (nearly doubling in the last year), with tens of thousands of edits every day. Hundreds of gigabytes of data now reside in the OpenStreetMap database, all open and freely available. Commercial companies like MapQuest, Foursquare, MapBox, Flickr, and others are using OpenStreetMap data as the mapping provider for their platforms and services. Wikipedia is even using OpenStreetMap as the map source in their mobile app, as well as for many maps within wiki articles.

What OpenStreetMap is bringing to the table that other open data initiatives have struggled with is the ability to incorporate user contribution, and even more importantly, to invite engagement and a sense of co-ownership on the part of the contributor. With OpenStreetMap, no individual party is responsible for the data, everyone is. In the Wikipedia ecosystem, active editors tend to act as shepherds or monitors of articles to which they’ve heavily contributed. OpenStreetMap creates this same sense of responsibility for editors based on geography. If an active user maps his or her entire neighborhood, the feeling of ownership is greater, and the user is more likely to keep it up to date and accurate.

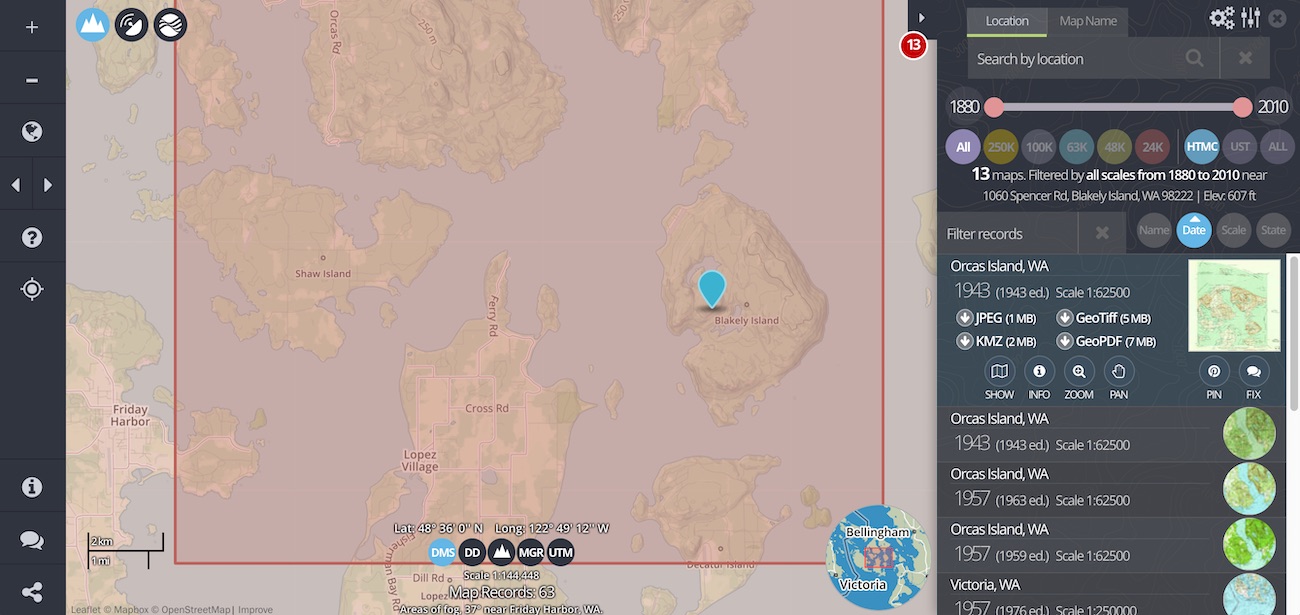

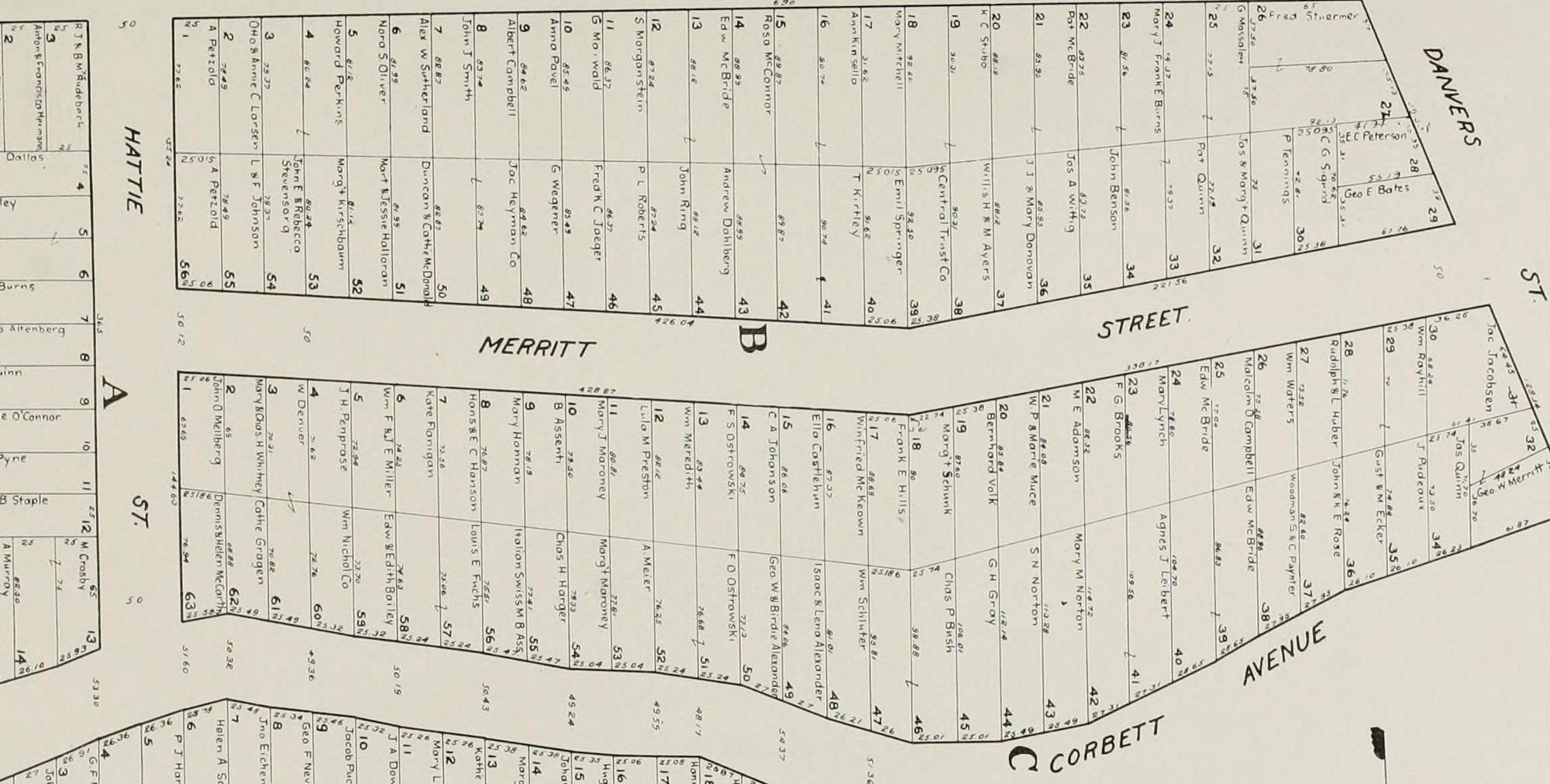

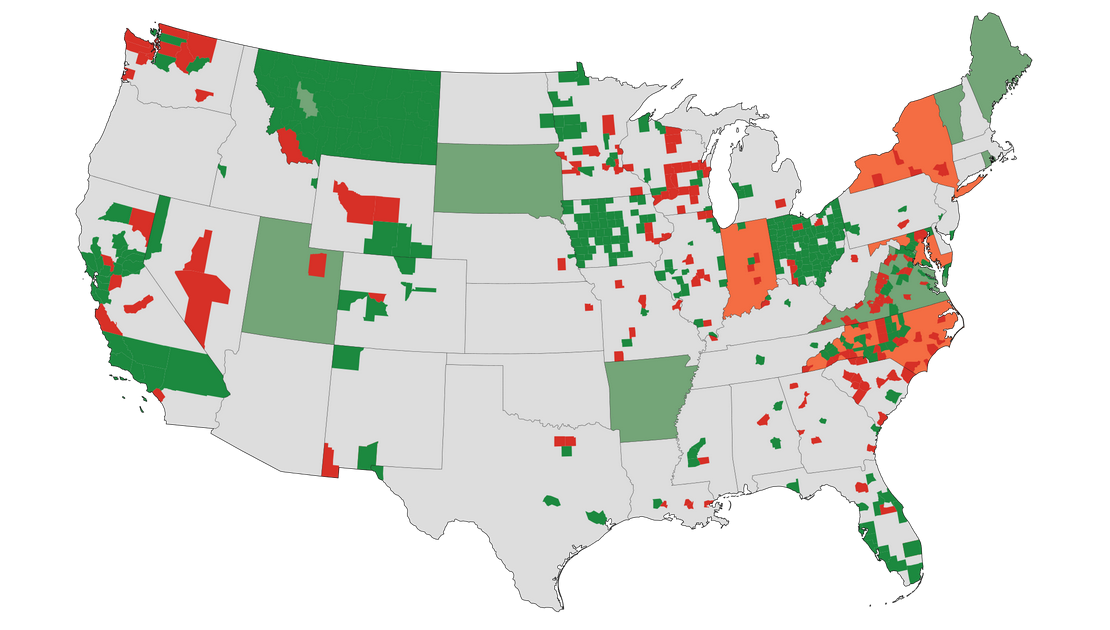

Open sources of map data are not new. Government departments from countries around the world have made their maps available for free for years, dating back to paper maps in libraries – certainly a great thing from a policy perspective that these organizations place value on transparency and availability of information. The US Census Bureau publishes a dataset of boundaries, roads, and address info in the public domain (TIGER). The UK’s Ordnance Survey has published a catalog of open geospatial data through their website. GeoNames.org houses a database of almost ten million geolocated place names. There are countless others, ranging from small, city-scale databases to entire country map layers. Many of these open datasets have even made their way into OpenStreetMap in the form imports, in which the OSM community occasionally imports baseline data for large areas based on pre-existing data available under a compatible license. In fact, much of the street data present in the United States data was imported several years ago from the aforementioned US Census TIGER dataset.

Open geodata sources are phenomenal for transparency and communication, but still lack the living, breathing nature of Wikipedia articles and GitHub repositories. “Crowdsourcing” has become the buzzword with public agencies looking to invite this type of engagement in mapping projects, to widely varying degrees of success. Feedback loops with providers of open datasets typically consist of “report an issue” style funnels, lacking the ability for direct interaction from the end user. By allowing the end user to become the creator, it instills a sense of ownership and responsibility for quality. As a contributor, I’m left to wonder about my change request. “Did they even see my report that the data is out of date in this location? When will it be updated or fixed?” The arduous task of building a free map of the entire globe wouldn’t even be possible without inviting the consumer back in to create and modify the data themselves.

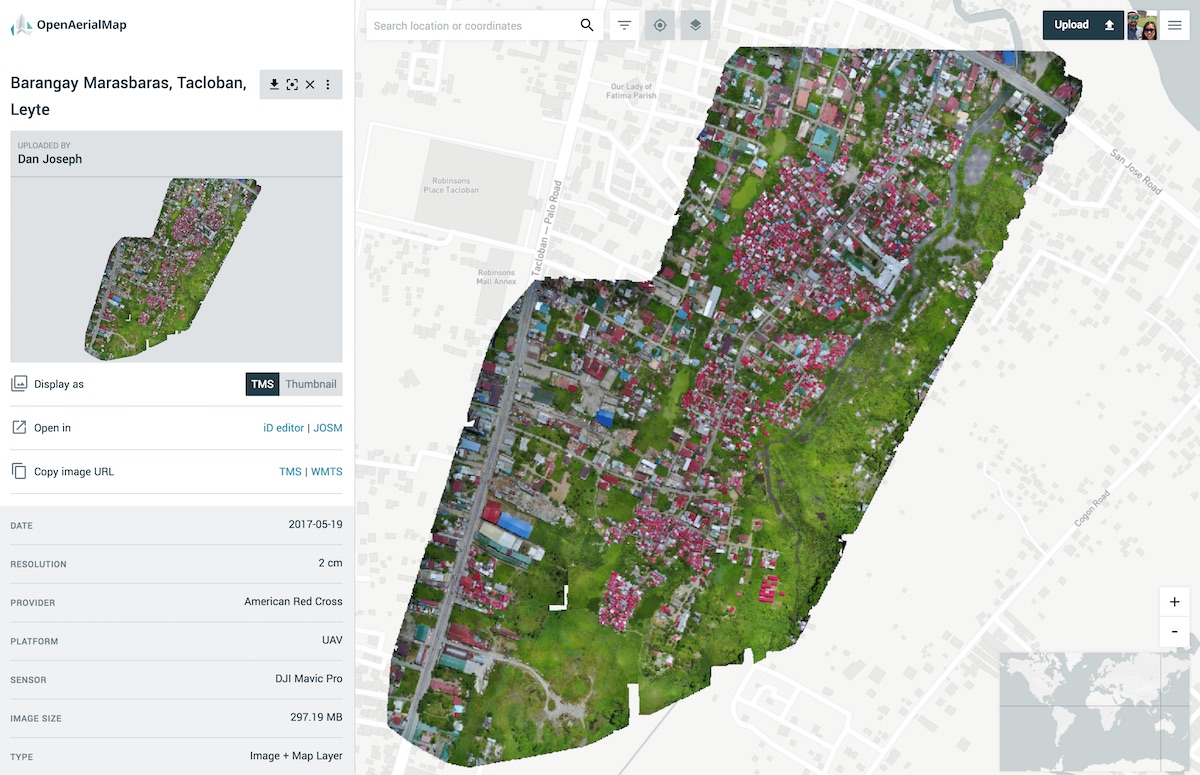

Enabling this combination of contribution and engagement for OpenStreetMap is an impressive stack of technology that powers the system, all driven by a mesh of interacting open source software projects under the hood. This suite of tools that drives the database, makes it editable, tracks changes, and publishes extracted datasets for easy consumption is produced by a small army of volunteer software developers collaborating to power the OpenStreetMap engine. While building this software stack is not the primary objective of OSM, it’s this that makes becoming a “mapper” possible. There are numerous editing tools available to contributors, ranging from the very simple for making small corrections, to the power tools for mass editing by experts. This narrowing of the technical gap between data and user allows the novice to make meaningful contribution and feel rewarded for taking part. Wikipedia would not be much today without the simplicity of clicking a single “edit” button. There’s room for much improvement here for OpenStreetMap, as with most collaboration-driven projects, and month-by-month the developer community narrows this technical gap with improvements to contributor tools.

In many ways, the roadblocks to adoption of open models for creating and distributing geodata aren’t ones of policy, but of technology and implementation. Even with ostensibly “open data” available through a government website, data portals are historically bad at giving citizens the tools to get their hands around that data. In the geodata publishing space, the variety of themes, file sizes, and different data formats combine to complicate the process of making the data conveniently available to users. What good is a database I’m theoretically allowed to have a copy of when it’s in hundreds of pieces scattered over a dozen servers? “Permission” and “accessibility” are different things, and both critical aspects to successful open initiatives. A logical extension of opening data, is opening access to that data. If transparency, accountability, and usability are primary drivers for opening up maps and data, lowering the bar for access is critical to make those a reality.

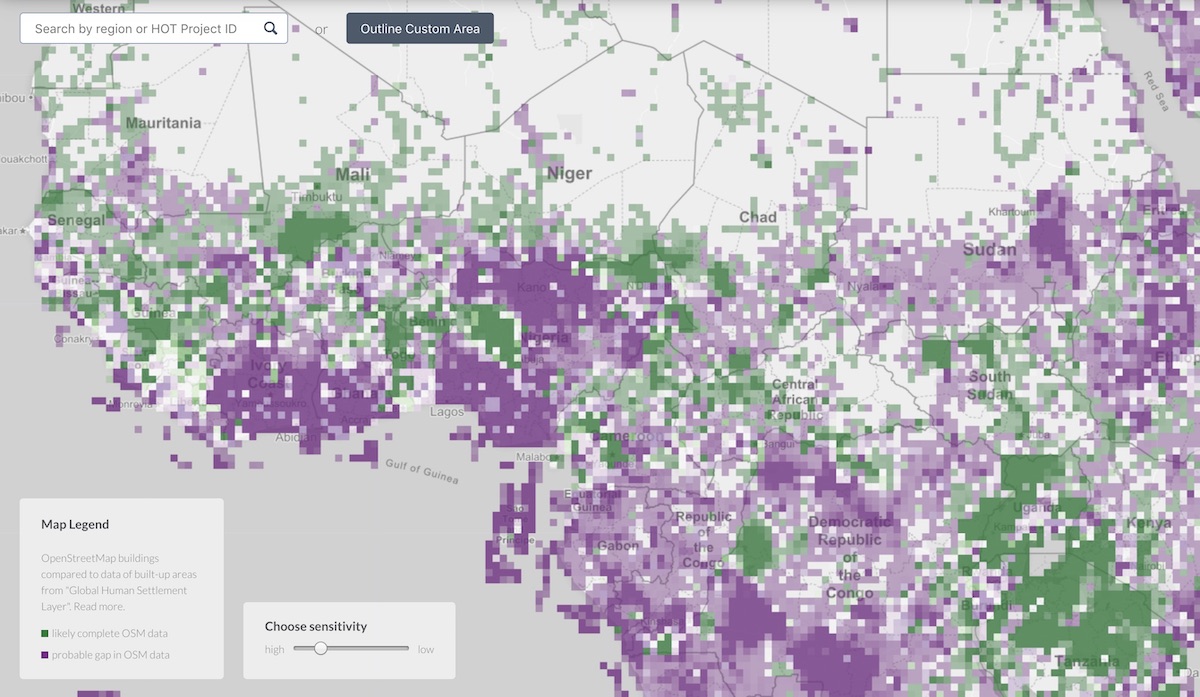

A great example the power of the engagement feedback loop with OpenStreetMap is the work of the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s (HOT) work over the past few years. HOT kicked off in 2009 to coordinate the resources resident in the OpenStreetMap community and apply them to assist with humanitarian aid projects. Working both remotely and on the ground, the first large scale effort undertaken by HOT was mapping in response to the Haiti earthquake in early 2010. Since then, HOT has grown its contributor base into the hundreds, and has connected with dozens of governments and NGOs worldwide—such as UNOCHA, UNOSAT, and the World Bank—to promote open data, sharing, transparency, and collaboration to assist in the response to humanitarian crises. To see the value of their work, you need look no further than the many examples showing OpenStreetMap data for the city of Port-au-Prince, Haiti before and after the earthquake. In recent months, HOT has activated to help with open mapping initiatives in Indonesia, Senegal, Congo, Somalia, Pakistan, Mali, Syria, and others.

One of the most exciting things about HOT, aside from the fantastic work they’ve facilitated in the last few years, is that it provides a tangible example for why engagement is such a critical component to organic growth of open data initiatives. The OpenStreetMap contributor base, which now numbers in the hundreds of thousands, can be mobilized for volunteer contribution to map places where that information is lacking, and where it has a direct effect on the capabilities of aid organizations working in the field. With a traditional, top-down managed open data effort, the response time would be too long to make immediate use of the data in crisis.

Another unspoken benefit to the OpenStreetMap model for accepting contributions from a crowd is the fact that hyperlocal map data benefits most from local knowledge. There’s a strong desire for this sort of local reporting on facts and features on the ground all over the world, and the structure of OpenStreetMap and its user community suits this quite naturally. Mappers tend to map things nearby, things they know. Whether it’s a mapper in a rural part of the western United States, a resort town in Mexico, or a flood-prone region in Northern India, there’s always a consumer for local information, and often times from those for whom it’s prohibitively expensive to acquire. In addition to the expertise of local residents contributing to the quality of available data, we also have local perspective that can be interesting, as well. This can be particularly essential to those humanitarian crises, as there’s a tendency for users to map things that they perceive as higher in importance to the local community.

Of course OpenStreetMap isn’t a panacea to all geospatial data needs. There are many requirements for mapping, data issue reporting, and opening of information where the data is best suited to more centralized control. Data for things like electric utilities, telecommunications, traffic routing, and the like, while sometimes publishable to a wide audience, still have service dependencies that require centralized, authoritative management. Even with data that requires consolidated control by a government agency or department, though, the principles of engagement and short feedback loops present in the OpenStreetMap model could still be applied, at least in part. Regardless of the model, getting the most out of an open access data project requires an ability for a contributor to see the effect of their contribution, whether it’s an edit to a Wikipedia page, or correcting a one way street on a map.

With geodata, openness and accessibility enable a level of conversation and direct interaction between publishers and contributors that has never been possible with traditional unilateral data sharing methods. OpenStreetMap provides a mature and real-world example of why engagement is often that missing link in the success of open initiatives.

The complete book is available as a free PDF download, or you can buy a print copy here.

With the growth of the open data movement, governments and data publishers are looking to enhance citizen participation. OpenStreetMap, the wiki of world maps, is an exemplary model for how to build community and engagement around map data. Lessons can be learned from the OSM model, but there are many places where OpenStreetMap might be the place for geodata to take on a life of its own.

With the growth of the open data movement, governments and data publishers are looking to enhance citizen participation. OpenStreetMap, the wiki of world maps, is an exemplary model for how to build community and engagement around map data. Lessons can be learned from the OSM model, but there are many places where OpenStreetMap might be the place for geodata to take on a life of its own.