Monthly Reading, August 2023

August 29, 2023 • #This post appeared in issue #36 of my newsletter, Res Extensa, where I write about the intersection of product design, bottoms-up systems, innovation, and what we can learn from the history of technology. I’d love it if you subscribed.

💡 Good Decision, Bad Decision, Indecision, and Fake Decision

The older I get, the more I appreciate two fundamental skills in every line of work:

- A respect for and ability to assess trade-offs, and

- Knowing how and when to make decisions

Notice it doesn’t say what decision to make. Effective decision-making means knowing which resources to bring to bear, who to involve, and how to zoom out on the upsides and downsides (number 1). And just as critically, it’s knowing when a decision is necessary. On most things, the faster decision is better. Whether we acknowledge it or not, most decisions are two-way doors: we can recover from the downsides. But surprisingly often it’s about knowing when we don’t really need a decision right now. Not deciding is itself a decision.

Austin Yang says it this way:

What most people aren’t aware of is that indecision in itself is a decision. You are essentially choosing to stick with the status quo for the time being.

A key factor to how we think about a decision is what action follows. “Indecision” only feels bad if we keep harping on the subject, if we continue deliberating even after we decided to stick with the status quo.

He raises another all-too-common problem where the follow-on action makes the decision problematic: the “fake decision”:

There is one type of decision that doesn’t get talked about enough. These are decisions that get made, but never acted on. I call them “fake decisions.” Technically speaking, they cannot be called decisions at all. They are simply feel-good exercises to fool yourself into thinking that something has changed.

🐄 Age of Invention: Cash Cows

Economic historian Anton Howes writes a newsletter devoted to the topic: what gave rise to the “improving mentality”? For some reason — a combination of timing, the weird semi-isolated, evolved culture of England, access to natural resources, political freedom — the British Isles was a petri dish of innovation in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Anton tells the story of Robert Bakewell, a cattle farmer that set out, through experimentation, trial and error, to improve his cattle herd.

Bakewell’s story could have been an unremarkable one. He was born, farmed, and died at Dishley, much like his father before him. But Bakewell, unlike most people, caught the improving mentality, or attitude — the one thing all inventors, both then and now, have in common — which had him viewing everything around him in terms of its capacity for betterment. The improving mentality was a reframing the status quo as a problem to solve. A habit of optimisation. A compulsion to perfect.

Through dozens of adjustments and a constant drive to improve, his cows were special. But it took active effort, experimentation, and drive to improve. He selectively bred his cattle to have larger backs, with the more expensive sirloin and filets, and smaller mid and lower sections, with their cheaper cuts.

Bakewell’s cows and sheep became extraordinarily valuable when sold for meat, though he soon discovered he could make even more money by leasing out the young males of his breeds to other farmers so that they could improve their own — “but never as good as that of Mr Bakewell who has both the male and the female”. Recognising how essential it was that he not lose his competitive advantage, he even set up his own abattoir and sold only dead meat, for fear that an unscrupulous butcher might be tempted to breed from the live animals sent to slaughter.

Progress shouldn’t be taken for granted! It takes optimism and effort to make it happen.

📚 Andy Matuschak — Self-Teaching, Spaced Repetition, Why Books Don’t Work

From Dwarkesh Patel’s excellent podcast, this is a masterclass in how learning works. I love how Andy is always essentially thinking out loud, as he’s in conversation, about the topic. Even a guy with his pedigree realizes that a subject like this is a confoundingly complex, with no “best” way of understanding it.

One of the biggest learnings from Andy is how to be purposeful when you read. You should ask questions of the text! I know this technique and still too often I read something knowing — sometimes consciously, usually subconciously — that I don’t truly understand what I just read. Just take a look at this session where Andy reads and makes notes on a paper in real-time, and you’ll see this in action.

🏃♂️ Speed matters: Why working quickly is more important than it seems

From James Somers:

The obvious benefit to working quickly is that you’ll finish more stuff per unit time. But there’s more to it than that. If you work quickly, the cost of doing something new will seem lower in your mind. So you’ll be inclined to do more.

The converse is true, too. If every time you write a blog post it takes you six months, and you’re sitting around your apartment on a Sunday afternoon thinking of stuff to do, you’re probably not going to think of starting a blog post, because it’ll feel too expensive.

Also at work, the better you get, the better you better get:

It is a truism, too, in workplaces, that faster employees get assigned more work. Of course they do. Humans are lazy. They want to preserve calories. And it’s exhausting merely thinking about giving work to someone slow. When you’re thinking about giving work to someone slow, you run through the likely quagmire in your head; you visualize days of halting progress. You imagine a resource—this slow person—tied up for awhile. It’s wearisome, even in the thinking. Whereas the fast teammate—well, their time feels cheap, in the sense that you can give them something and know they’ll be available again soon. You aren’t “using them up” by giving them work. So you route as much as you can through the fast people. It’s ironic: your company’s most valuable resources—because they finish things quickly—are the easiest to consume.

Feedback loops, both positive and negative, are a helluva thing.

🧱 The Pattern Language of Project Xanadu

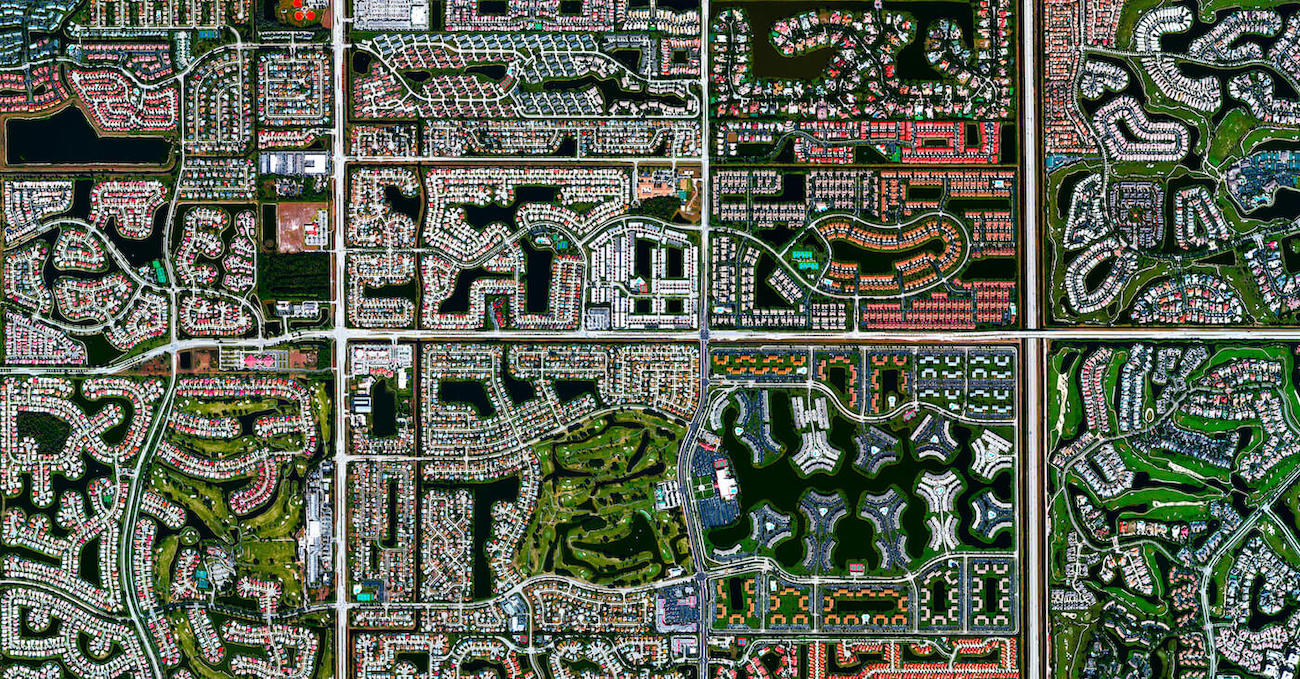

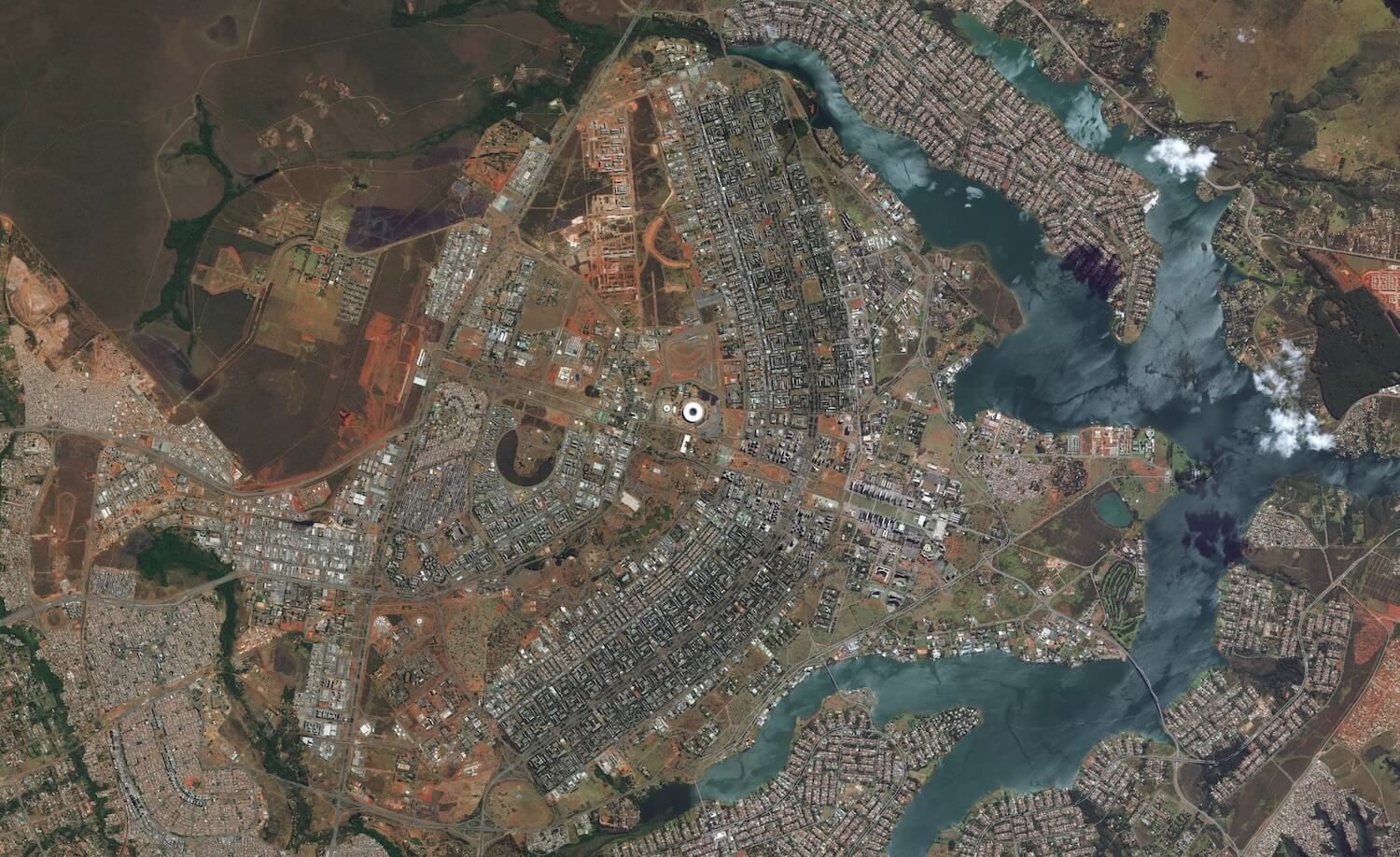

Architect Christopher Alexander articulated the notion of “pattern languages” in his 1977 book of the same name. You devise a library of rules of thumb for designing (in his case, living spaces — neighborhoods, buildings, rooms) that work well together. Rather than rigid top-down design with hard specs, a well-thought-out pattern language gives the designer room to be creative while still working from thoughtful, functional constraints. An effective pattern language is a hierarchical scheme of composable building blocks: in Alexander’s original language, “Cozy Half-Enclosed Corner” works well with “Light on Two Sides”, or with “Seat Spots in Light and Dark”.

Pattern languages are meant to be sets of general principles. No neighborhood conforms to “The Pattern Language” as a standard.

In the world of software, Ted Nelson’s Project Xanadu is both an epic failure and wild success. It started as a proposal in 1960, and still doesn’t exist.

But as Maggie Appleton points out here, many of the project’s proposed “patterns” have been embraced and implemented in the distributed ecosystem of Internet specifications and software features over the past few decades:

People are building Xanadu without knowing what Xanadu is. Which is the essence of a good pattern language; true patterns evolve naturally within systems, and are found rather than crafted.

We should think of Xanadu as a successful pattern language, rather than a failed software project.

🛕 Anachronistic History

The past couple weeks I’ve been experimenting tons with ChatGPT and Midjourney, figuring out how to make practical use of this new wave of products.

Tinkering around, I asked ChatGPT:

Write about some creative anachronistic historical events.

And here’s a brief sampling of what I got:

Aztec Airborne Armada (1400s): The Aztecs develop an array of helium-filled airships, forming an airborne armada to defend their empire and launch surprise attacks on neighboring civilizations.

Socrates’ Philosophical Podcast (399 BCE): Instead of written dialogues, Socrates engages in thought-provoking discussions through an ancient form of podcasting, spreading his philosophical ideas through the airwaves of Athens.

Marco Polo’s Transcontinental Railroad (1271-1295): Marco Polo’s extensive travels result in a collaborative effort among the nations he encountered to construct a massive transcontinental railroad network connecting Europe, Asia, and Africa centuries ahead of its time.

See the full post for more.

🥪 Nibble and Your Appetite Will Grow

From Stephen Ango:

There’s a French expression I like:

L’appétit vient en mangeant

Appetite comes when you eat. Nibble and your appetite will grow.

Appetite can be the hunger for any kind of thing, not just food. Some days I wish I had the appetite to write, to read, to exercise, or even go outside.

Procrastination is the state of waiting for motivation to come. Paradoxically, the most reliable way to create motivation is to start doing the thing.